March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The whites imposed social, economic, and political repression against black people into the 1960s, under a system of legal discrimination known as Jim Crow laws, which were pervasive in the American South.

With Bayard Rustin, Randolph called for 100,000 black workers to march on Washington,[3] in protest of discriminatory hiring during World War II by U.S. military contractors and demanding an Executive Order to correct that.

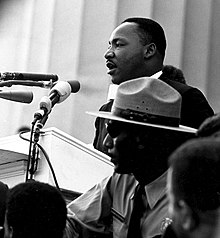

[19] Their Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, held at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, featured key leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Roy Wilkins.

That year violent confrontations broke out in the South: in Cambridge, Maryland; Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Goldsboro, North Carolina; Somerville, Tennessee; Saint Augustine, Florida; and across Mississippi.

[24] On May 24, 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy invited African-American novelist James Baldwin, along with a large group of cultural leaders, to a meeting in New York to discuss race relations.

That night (early morning of June 12, 1963), Mississippi activist Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway, further escalating national tension around the issue of racial inequality.

Leaders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who wanted to conduct direct actions against the Department of Justice, endorsed the protest before they were informed that civil disobedience would not be allowed.

[39]Mobilization and logistics were administered by Rustin, a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first of the Freedom Rides to test the Supreme Court ruling that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel.

Randolph, King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) believed it could raise both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill.

[50] When William C. Sullivan produced a lengthy report on August 23 suggesting that Communists had failed to appreciably infiltrate the civil rights movement, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover rejected its contents.

They gathered early this morning [August 27] in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park, where state troopers once [four months previous in May] used fire hoses and dogs to put down their demonstrations.

[44]Some participants who arrived early held an all-night vigil outside the Department of Justice, claiming it had unfairly targeted civil rights activists and that it had been too lenient on white supremacists who attacked them.

[66] Major League Baseball cancelled two games between the Minnesota Twins and the last place Washington Senators although the venue, D.C. Stadium, was nearly four miles from the Lincoln Memorial rally site.

The FBI and Justice Department refused to provide preventive guards for buses traveling through the South to reach D.C.[67] William Johnson recruited more than 1,000 police officers to serve on this private force.

[70] The committee, notably Rustin, agreed to move the site on the condition that Reuther pay for a $19,000 (equivalent to $172,500 in 2021) sound system so that everyone on the National Mall could hear the speakers and musicians.

On Meet the Press, reporters grilled Roy Wilkins and Martin Luther King Jr. about widespread foreboding that "it would be impossible to bring more than 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting."

Dancer and actress Josephine Baker gave a speech during the preliminary offerings, but women were limited in the official program to a "tribute" led by Bayard Rustin, at which Daisy Bates also spoke briefly (see "excluded speakers" below.)

[89] The opening remarks were given by march director A. Philip Randolph, followed by a tribute to "Negro Women Fighters for Freedom", in which Daisy Bates spoke briefly in place of Myrlie Evers, who had missed her flight.

[43][98] Deleted from his original speech at the insistence of more conservative and pro-Kennedy leaders[3][99] were phrases such as:In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late.

We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently ... Lewis' speech was distributed to fellow organizers the evening before the march; Reuther, O'Boyle, and others thought it was too divisive and militant.

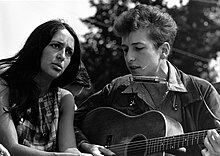

Dylan also performed "Only a Pawn in Their Game", a provocative and not completely popular choice because it asserted that Byron De La Beckwith, as a poor white man, was not personally or primarily to blame for the murder of Medgar Evers.

There were also quite a few white and Latino celebrities who attended or helped fund the March in support of the cause: Tony Curtis, James Garner, Robert Ryan, Charlton Heston, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Rita Moreno, Marlon Brando, Bobby Darin and Burt Lancaster, among others.

In his section The March on Washington and Television News, William Thomas notes: "Over five hundred cameramen, technicians, and correspondents from the major networks were set to cover the event.

[46] Commented Michael Thelwell of SNCC: "So it happened that Negro students from the South, some of whom still had unhealed bruises from the electric cattle prods which Southern police used to break up demonstrations, were recorded for the screens of the world portraying 'American Democracy at Work.

"[139] SNCC organizer Bob Zellner reported that the event "provided dramatic proof that the sometimes quiet and always dangerous work we did in the Deep South had had a profound national impact.

"[140] Richard Brown, then a white graduate student at Harvard University, recalls that the March fostered direct actions for economic progress: "Henry Armstrong and I compared notes.

However, some black nationalist intellectuals did not see that the liberal reforms of the Johnson administration would assure "full integration" based upon the existing power structures and persisting racist culture of daily life in America.

Black Panther Party member and lawyer Kathleen Cleaver held radical views that only revolution could transform American society to bring about the redistribution of wealth and power that was needed to end the historical facts of exclusion and inequality.

[152] The NAACP's Virtual March featured performances from Macy Gray, Burna Boy, and speeches from Stacey Abrams, Nancy Pelosi, Cory Booker, and Mahershala Ali, among many others.

They further argued that although legal advances were made, black people still live in concentrated areas of poverty ("ghettoes"), where they receive inferior education and suffer from widespread unemployment.