Jim Creighton

James Creighton, Jr. (April 15, 1841 – October 18, 1862) was an American baseball player during the game's amateur era, and is considered by historians to be the sport's first superstar and one of its earliest paid competitors.

During this early, pre-professional period of baseball's evolution, Creighton's pitching technique changed the sport from a game that showcased hitting, running, and fielding into a confrontation between the pitcher and batter.

The speed with which Creighton was able to hurl the ball had previously been considered impossible without movement of the elbow or wrist, which was prohibited by existing rules.

[3] During this period, there were no organized leagues and few competing teams, so amateur clubs spent much of their time practicing and playing intra-squad games, with occasional matches against rivals.

[4] Under the rules of baseball at the time, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball underhanded with arm locked straight at the elbow and at the wrist.

"[5] It was the job of the pitcher to make it easy for the batter to hit the ball as fielding was considered the game's true skill.

All but Henry Brainard were quietly paid a salary, with Creighton earning $500, thus making these men some of the earliest "professional" baseball players.

[3] While the practice of pay-for-play unofficially spread throughout baseball in the coming years, open professionalism didn't begin until the 1869 season, when the Cincinnati Red Stockings paid a salary to each member of the team.

On October 14, 1862, Creighton played second base in a match on the Excelsior Grounds against the Union of Morrisania club, while Brainard pitched.

As chronicled 50 years later by a witness to the game, Jack Chapman, Creighton took over pitching duties from Brainard in the sixth inning, and in his next at bat hit a home run.

[notes 1] According to Chapman, when Creighton crossed home plate, he commented to the next batter, George Flanley, that he heard something snap.

"Dying while hitting a long home run is a great story; it's just not true," said Tom Shieber, senior curator of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[15] Shieber researched original news sources and found no references to Creighton hitting a home run in that game.

Though it is generally accepted that Creighton fatally injured himself while playing baseball, it was reported that the Excelsior president, Dr. Joseph Jones, made comments during the National Association convention of 1862 that constituted an attempt to "correct" this notion.

[18] Later research claims that Dr. Jones' assertions are correct; Creighton had died of a "strangulated intestine", and did not hit a home run during his final game.

[19] Dr. Jones' remarks have been interpreted as his attempt to save baseball's image, and its nearly equal standing with cricket, as well as his team's legacy after losing their best player.

[3] Baseball at the time was constantly "looking forward", and Creighton's death provided the sport with a certain mythology and much-needed nostalgia.

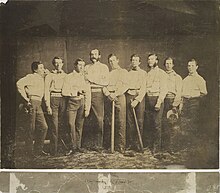

"[21] For years following his death, the Excelsiors' program included a portrait of their team with Creighton, shrouded in black, featured prominently in the center.

[21] Creighton's indirect legacy is perhaps most profoundly seen in what is now considered a fundamental component of the game: the called ball and the walk.

[19] In 2014, after a successful funding campaign to restore the monument, a replica of the original finial was installed and unveiled during a public ceremony.

The television series The Simpsons made reference to Creighton in the Season 3 episode "Homer at the Bat", where Mr. Burns has him pegged as the right fielder for his company's softball team.