Joan II of Navarre

Joan's paternity was dubious because her mother was involved in a scandal, but Louis declared her his legitimate daughter before he died in 1316.

In 1322, Philip V was succeeded by his brother Charles IV in both France and Navarre, but most Navarrese lords refused to swear loyalty to him.

After Charles IV died in 1328, the Navarrese expelled the French governor and declared Joan the rightful monarch of Navarre.

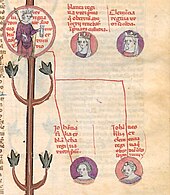

[3] Her father was the oldest son and heir of King Philip IV of France and Queen Joan I of Navarre.

[3] According to an agreement of the most powerful French lords, which was completed on 16 July, if Clementia gave birth to a son, the son was to be crowned King of France, but if a daughter was born, she and Joan could only inherit the Kingdom of Navarre and the counties of Champagne and Brie (the three realms that Louis X had inherited from his mother, Joan I of Navarre).

[8] It was also agreed that Joan was to be sent to her mother's relatives in Burgundy, but her marriage could not be decided without the consent of the members of the French royal family.

[12] Joan's maternal grandmother, Agnes of France, Duchess of Burgundy, sent letters to the leading French lords, protesting against his coronation, but Philip V mounted the throne without real opposition.

[13] In another letter, Odo IV argued that the disinheritance of Joan by Philip V went against "the divine right of law, by custom, in the usage kept in similar cases in empires, kingdoms, fiefs, in baronies in such a length of time that there is no memory of the contrary".

[16] His brother, Charles the Fair, who was Philip IV's last surviving son, succeeded him in both France and Navarre.

[16][22] Since Charles's widow, Joan of Évreux, was pregnant, the peers of France and other influential French lords assembled in Paris to elect a regent.

[22] The majority of the French lords concluded that Philip of Valois had the strongest claim to the office, because he was the closest patrilinear relative of the deceased king.

[23] The representatives of the Estates of the realm in Navarre, who assembled at Puente La Reina on 13 March,[24] replaced the French governor with two local lords.

[16][26] Her birth made it clear that the direct male line of the royal Capetian dynasty of France had become extinct with Charles the Fair's death.

[27] To strengthen his position in France, in July Philip acknowledged the right of Joan and her husband to rule Navarre.

[12] During the following months, Joan and her husband conducted lengthy negotiations with the Estates of the realm, especially about the role of Philip of Évreux in the administration of the kingdom.

[31] The delegates of the general assembly first declared that Philip would be allowed to take part in the administration of Navarre in a meeting in Roncesvalles in November 1328.

[32] However, they also stated that all traditional elements of the coronation (including the new monarch's elevation on a shield and the throwing of money to spectators) would only be carried out in connection with Joan.

[33][32] To emphasize Philip's claim to reign in his wife's realm, Henry de Sully referred to Paul the Apostle who had stated that "the head of woman is man" in his First Epistle to the Corinthians.

[35] However, the Navarrese also specified that both Joan and Philip were to renounce the crown as soon as their heir reached twenty-one, or they were obliged to pay a fine of 100,000 livres.

[34][43] Historian Elena Woodacre notes, the "royal couple had to balance the needs of their French territories alongside the rule of Navarre", which forced them to split their time between all of their domains.

[43] Joan and Philip could hardly get accustomed to the "tastes and customs of the Navarrese, and were alien to their language", according to historian José María Lacarra, for which they were often absent from the kingdom.

[30] Joan decided to again visit Navarre, but she never returned, most probably because of the possibility of an invasion of her family's domains in France during the Hundred Years War.

[45] She and her husband had supported Philip VI against Edward III of England, who claimed the French throne as the son of Joan's aunt Isabella.

In November she boldly concluded a truce with the Earl of Lancaster, granting Edward's troops free passage through her county of Angoulême in return for protection of her lands.

[12] They were efficient as co-rulers but no evidence attests to the closeness of their personal relationship, in contrast to the well-documented marriages of Joan's grandparents, father and uncles.