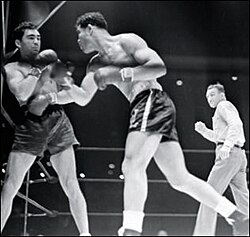

Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling

[3] Louis' celebrity was particularly important for African Americans of the era, who were not only suffering economically along with the rest of the country but also were the targets of significant racially motivated violence, particularly in Southern states by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

By the time of the Louis-Schmeling match, Schmeling was thought of as the final stepping stone to Louis' eventual title bid.

Max Schmeling, on the other hand, was born in Germany, and he had become the first world heavyweight champion to win the title by disqualification in 1930, against American Jack Sharkey.

Nevertheless, many boxing fans considered Schmeling, 30 years old by the time of his first match with Louis, to be on the decline and not a serious challenge for the Brown Bomber.

As the fight progressed, stunned fans and critics alike watched Schmeling continue to use this style effectively, and Louis had no idea how to solve the puzzle.

Louis remained busy, trying to land a punch that would give him a knockout victory, but, with eyesight trouble and Schmeling's jab constantly in his face, this proved impossible.

[9] Hughes described the national reaction to Louis' defeat in these terms: I walked down Seventh Avenue and saw grown men weeping like children, and women sitting in the curbs with their heads in their hands.

Hitler contacted Schmeling's wife, sending her flowers and a message: "For the wonderful victory of your husband, our greatest German boxer, I must congratulate you with all my heart.

[8]After his victory over Louis, Schmeling negotiated for a title bout with world heavyweight champion James J. Braddock.

"[12] Schmeling kept his Jewish manager, Joe Jacobs, despite significant pressure,[13] and, in a dangerous political gamble, refused the "Dagger of Honor" award offered by Adolf Hitler.

[14][15] In fact, Schmeling had been urged by his friend and legendary ex-champion Jack Dempsey to defect and declare American citizenship.

Schmeling was picketed at his hotel room, received a tremendous amount of hate mail, and was assaulted with cigarette butts and other detritus as he approached the ring.

"[20] A few days before the fight, the New York State Athletic Commission had ruled that Joe Jacobs, Schmeling's manager, was ineligible to work in the German's corner, or be in the locker room, as punishment for a previous public relations infraction involving fighter "Two-Ton" Tony Galento.

[21] As a result, Schmeling sat anxiously in the locker room before the bout; in contrast, Louis took a two-hour nap.

Among the more than 70,000 fans in attendance were Clark Gable, Douglas Fairbanks, Gary Cooper, Gregory Peck, and J. Edgar Hoover.

Schmeling came out of his corner trying to utilize the same style that got him the victory in their first fight, with a straight-standing posture and his left hand prepared to begin jabbing.

Before the fight, he mentioned to his trainer Jack "Chappie" Blackburn that he would devote all his energy to the first three rounds,[21] and even told sportswriter Jimmy Cannon that he predicted a knockout in one.

[25] Schmeling's cornerman Max Machon threw a towel in the ring – although, under New York state rules, this did not end the fight.

In his autobiography, Schmeling himself confirmed the public's reaction to the outcome, recounting his ambulance ride to the hospital afterward: "As we drove through Harlem, there were noisy, dancing crowds.

The whole area was filled with celebration, noise, and saxophones, continuously punctuated by the calling of Joe Louis' name.

"[3] Reaction in the mainstream American press, while positive toward Louis, reflected the implicit racism in the United States at the time.

Lewis F. Atchison of The Washington Post began his story: "Joe Louis, the lethargic, chicken-eating young colored boy, reverted to his dreaded role of the 'brown bomber' tonight"; Henry McLemore of the United Press called Louis "a jungle man, completely primitive as any savage, out to destroy the thing he hates.

[28] Although Schmeling rebounded professionally from the loss to Louis (winning the European Heavyweight Title in 1939 by knocking out Adolf Heuser in the 1st round), the Nazi regime would cease promoting him as a national hero.

Louis went on to become a major celebrity in the United States and is considered the first true African American national hero.

[29] When other prominent blacks questioned whether African Americans should serve against the Axis nations in the segregated U.S. Armed Forces, Louis disagreed, saying, "There are a lot of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain't gonna fix them."

[31] Louis got a job as a greeter at the Caesars Palace hotel in Las Vegas, and Schmeling flew to visit him every year.

Louis was reportedly so in need of money, but too damaged to box anymore, so the former champion took up professional wrestling to make ends meet.

[33] The paradox, as identified by Neale, is that the general rule that monopoly is the "ideal market position of a firm" does not hold for professional sports.