Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

During his first ten years in Weimar, Goethe became a member of the Duke's privy council (1776–1785), sat on the war and highway commissions, oversaw the reopening of silver mines in nearby Ilmenau, and implemented a series of administrative reforms at the University of Jena.

During this period Goethe published his second novel, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship; the verse epic Hermann and Dorothea, and, in 1808, the first part of his most celebrated drama, Faust.

The young Goethe received from his father and private tutors lessons in subjects common at the time, especially languages (Latin, Greek, Biblical Hebrew (briefly),[10] French, Italian, and English).

[11] He also had a devotion to the theater, and was greatly fascinated by the puppet shows that were annually arranged by occupying French Soldiers at his home and which later became a recurrent theme in his literary work Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

[13] In early literary attempts Goethe showed an infatuation with Gretchen, who would later reappear in his Faust, and the adventures with whom he would describe concisely in Dichtung und Wahrheit.

He detested learning age-old judicial rules by heart, preferring instead to attend the lessons of the university professor and poet Christian Fürchtegott Gellert.

In Leipzig, Goethe fell in love with Anna Katharina Schönkopf, the daughter of a craftsman and innkeeper, writing cheerful verses about her in the Rococo genre.

The two became close friends, and crucially to Goethe's intellectual development, Herder kindled his interest in William Shakespeare, Ossian and in the notion of Volkspoesie (folk poetry).

Although in his academic work he had given voice to an ambition to make jurisprudence progressively more humane, his inexperience led him to proceed too vigorously in his first cases, for which he was reprimanded and lost further clientele.

In a couple of weeks the biography was reworked into a colourful drama titled Götz von Berlichingen, and the work struck a chord among Goethe's contemporaries.

The author Daniel Wilson claims that Goethe engaged in negotiating the forced sale of vagabonds, criminals, and political dissidents as part of these activities.

During the course of his trip Goethe met and befriended the artists Angelica Kauffman and Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, as well as encountering such notable characters as Lady Hamilton and Alessandro Cagliostro.

Goethe's secretary Riemer reports: 'Although already undressed and wearing only his wide nightgown... he descended the stairs towards them and inquired what they wanted from him.... His dignified figure, commanding respect, and his spiritual mien seemed to impress even them.'

The earliest known account was of Karl Wilhelm Müller's, which gives all of his last words:[43] "Macht doch den zweiten Fensterladen in der Stube auch auf, damit mehr Licht hereinkomme."

[...]" John Ruskin, in his Præterita, narrates a memory of him from his diary record of 25 October 1874 that Carlyle "[...] had been quoting the last words of Goethe, 'Open the window, let us have more light' (this about an hour before painless death, his eyes failing him).

[53] In the last period, between Schiller's death, in 1805, and his own, appeared Faust Part One (1808), Elective Affinities (1809), the West-Eastern Diwan (an 1819 collection of poems in the Persian style, influenced by the work of Hafez), his autobiographical Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (From My Life: Poetry and Truth, published between 1811 and 1833) which covers his early life and ends with his departure for Weimar, his Italian Journey (1816–17), and a series of treatises on art.

The novel remains in print in dozens of languages and its influence is undeniable; its central hero, an obsessive figure driven to despair and destruction by his unrequited love for the young Lotte, has become a pervasive literary archetype.

What set Goethe's book apart from other such novels was its expression of unbridled longing for a joy beyond possibility, its sense of defiant rebellion against authority, and of principal importance, its total subjectivity: qualities that trailblazed the Romantic movement.

Later, a facet of its plot, i.e., of selling one's soul to the devil for power over the physical world, took on increasing literary importance and became a view of the victory of technology and of industrialism, along with its dubious human expenses.

Perhaps the single most influential piece is "Mignon's Song" which opens with one of the most famous lines in German poetry, an allusion to Italy: "Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn?"

Epigrams such as "Against criticism a man can neither protest nor defend himself; he must act in spite of it, and then it will gradually yield to him", "Divide and rule, a sound motto; unite and lead, a better one", and "Enjoy when you can, and endure when you must", are still in usage or are often paraphrased.

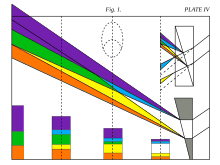

Although Goethe's empirical observations were largely accurate, his aesthetic approach failed to meet the standards of analytic and mathematical analysis used ubiquitously in modern Science.

A year before his death, in a letter to Sulpiz Boisserée, Goethe wrote that he had the feeling that all his life he had been aspiring to qualify as one of the Hypsistarians, an ancient sect of the Black Sea region who, in his understanding, sought to reverence, as being close to the Godhead, what came to their knowledge of the best and most perfect.

[88] At age 23, Goethe wrote a poem about a river, originally part of a dramatic dialogue, which he published as a separate work called Mahomets Gesang ("Muhammad's Song").

[104] In a letter written to Leopold Casper in 1932, Einstein wrote that he admired Goethe as 'a poet without peer, and as one of the smartest and wisest men of all time'.

[122][123] Eliot presented Goethe as "eminently the man who helps us to rise to a lofty point of observation" and praised his "large tolerance", which "quietly follows the stream of fact and of life" without passing moral judgments.

[122] Matthew Arnold found in Goethe the "Physician of the Iron Age" and "the clearest, the largest, the most helpful thinker of modern times" with a "large, liberal view of life".

[130][131] Both Diderot and Goethe exhibited a repugnance towards the mathematical interpretation of nature; both perceived the universe as dynamic and in constant flux; both saw "art and science as compatible disciplines linked by common imaginative processes"; and both grasped "the unconscious impulses underlying mental creation in all forms.

[131] His views make him, along with Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and Ludwig van Beethoven, a figure in two worlds: on the one hand, devoted to the sense of taste, order, and finely crafted detail, which is the hallmark of the artistic sense of the Age of Reason and the neo-classical period of architecture; on the other, seeking a personal, intuitive, and personalized form of expression and society, firmly supporting the idea of self-regulating and organic systems.

The Serbian inventor and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla was heavily influenced by Goethe's Faust, his favorite poem, and had actually memorized the entire text.