John Bell Hood

Bruce Catton wrote that "the decision to replace Johnston with Hood was probably the single largest mistake that either government made during the war."

Hood's education at the United States Military Academy led to a career as a junior officer in the infantry and cavalry of the antebellum U.S. Army in California and Texas.

[4] Transferred with many of Longstreet's troops to the Western Theater, Hood led a massive assault into a gap in the Union line at the Battle of Chickamauga but was wounded again, requiring the amputation of his right leg.

He was decisively defeated at the Battle of Nashville by his former West Point instructor, Major General George Henry Thomas, after which he was relieved of command.

[9] Notwithstanding his modest record at the academy, in 1860, Hood was appointed chief instructor of cavalry at West Point, a position he declined, citing his desire to remain with his active field regiment and to retain all of his options in light of the impending war.

[10] Hood was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry, served at Fort Jones, California, and later transferred to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry in Texas, where he was commanded by Col. Albert Sidney Johnston and Lt. Col. Robert E.

[11] While commanding a reconnaissance patrol from Fort Mason on July 20, 1857, Hood sustained the first of many wounds that marked his life in military service – an arrow through his left hand during action against the Comanches at Devil's River, Texas.

Hood and his horsemen won a victory at the Skirmish at Cedar Lane on July 12 near Newport News, capturing 12 men of the 7th New York Regiment of Volunteers as well as two deserters from Fort Monroe.

The brigade was initially formed the previous fall, led by ex-US Senator Louis T. Wigfall, but he resigned his command to take a seat in the Confederate Congress.

During the Battle of Antietam, Hood's division came to the relief of Stonewall Jackson's corps on the Confederate left flank, fighting in the infamous cornfield and turning back an assault by the U.S.

He requested permission from Longstreet to move around the left flank of the U.S. army, beyond the mountain known as [Big] Round Top, to strike the U.S. soldiers in their rear area.

He is tall, thin, and shy; has blue eyes and light hair; a tawny beard, and a vast amount of it, covering the lower part of his face, the whole appearance that of awkward strength.

[26]As he recuperated, Hood began a campaign to win the heart of the young, prominent South Carolina socialite Sally Buchanan Preston, known as "Buck" to her friends, whom he had first met while traveling through Richmond in March 1863.

[29] As darkness set in, he chanced upon Gen. John C. Breckinridge, former vice president of the United States, presidential candidate and senator from Kentucky, who also happened to be a cousin of Buck Preston.

[34] On the 20th, Hood led Longstreet's assault that exploited a gap in the Federal line, leading to the defeat of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans's U.S. Army of the Cumberland.

[36] In the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, was engaged in a campaign of maneuver against William T. Sherman, who was driving from Chattanooga toward Atlanta.

Despite his two damaged limbs, Hood performed well in the field, riding as much as 20 miles a day without apparent difficulty, strapped to his horse with his artificial leg hanging stiffly, and an orderly following closely behind with crutches.

The leg, made of cork, was donated (along with a couple of spares) by members of his Texas Brigade, who had collected $3,100 in a single day for that purpose; it had been imported from Europe through the U.S.

He told Bragg, "I have, General, so often urged that we should force the enemy to give us battle as to almost be regarded reckless by the officers high in rank in this army [meaning Johnston and senior corps commander William J. Hardee], since their views have been so directly opposite."

In William Hardee's June 22, 1864, letter to General Bragg, he stated, "If the present system continues we may find ourselves at Atlanta before a serious battle is fought."

Robert E. Lee gave an ambiguous reply to Davis's request for his opinion about the promotion, calling Hood "a bold fighter, very industrious on the battlefield, careless off".

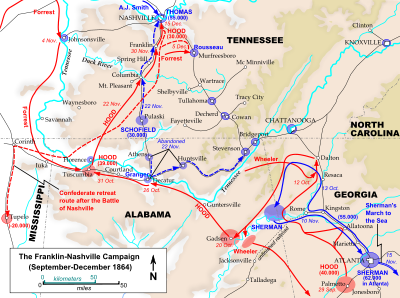

Hood's ambitious hope was that he could maneuver Sherman into a decisive battle, defeat him, recruit additional forces in Tennessee and Kentucky, and pass through the Cumberland Gap to come to the aid of Robert E. Lee, who was besieged at Petersburg.

However, the plan failed since Sherman felt this development furthered his current objective by removing opposing forces in his path, noting: "If he [Hood] will go to the Ohio River, I'll give him rations.

He also established a new theater commander to supervise Hood and the department of Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, although the officer selected for the assignment, Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, was not expected to exert any real operational control of the armies in the field.

Unwilling to abandon his original plan, Hood stumbled toward the heavily fortified capital of Tennessee and laid siege with inferior forces, which endured the beginning of a severe winter.

In a speech to his men, Hood hoped they would support Taylor and avenge their comrades "whose bones lay bleaching upon the fields of Middle Tennessee."

[53] In March 1865, Hood requested an assignment to the Trans-Mississippi Theater to report on the situation and assess the possibility of moving troops across the Mississippi River to reinforce the East.

Though rough, incomplete, and unpublished until after his death, this work served to justify his actions, particularly in response to what he considered misleading or false accusations made by Joseph E. Johnston and to negative portrayals in William Tecumseh Sherman's memoirs.

[65] Stephen Vincent Benét's poem "Army of Northern Virginia" included a passage about Hood: Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee Infantry "Maury Greys" wrote the following epitaph to Hood, published in various editions of his memoirs Company Aytch:[66] Watkins was also sympathetic with the Texas general and recounted the private Tennessean soldiers' honor of having to serve under him in several passages.

Our cause had been lost before he took command...[68]In Bell I. Wiley's 1943 book, The Life of Johnny Reb, the Common Soldier of the Confederacy, he recounts that after the defeats in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign, Hood's troops sang with wry humor a verse about him as part of the song The Yellow Rose of Texas.