John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

Bright also worked with Cobden in another free trade initiative, the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty of 1860, promoting closer interdependence between Great Britain and the Second French Empire.

[3] Tales of these early years circulated through Britain and the United States late into his career, to the extent that students at institutions such as the young Cornell University regarded him as an exemplar for activities such as the Irving Literary Society.

He was a fairly prosperous man of business, very happy in his home, always ready to take part in the social, educational and political life of his native town.

In 1839 he built the house which he called "One Ash", and he married Elizabeth, daughter of the Quaker minister Rachel (born Bragg) and the tanner Jonathan Priestman of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Bright is described by the historian of the League as "a young man then appearing for the first time in any meeting out of his own town, and giving evidence, by his energy and by his grasp of the subject, of his capacity soon to take a leading part in the great agitation.

Cobden spoke some words of condolence, but "after a time he looked up and said, 'There are thousands of homes in England at this moment where wives, mothers and children are dying of hunger.

He had been all over England and Scotland addressing vast meetings and, as a rule, carrying them with him; he had taken a leading part in a conference held by the Anti-Corn Law League in London had led deputations to the Duke of Sussex, to Sir James Graham, then home secretary, and to Lord Ripon and Gladstone, the secretary and undersecretary of the Board of Trade; and he was universally recognised as the chief orator of the Free Trade movement.

He took his seat in the House of Commons as one of the members for Durham on 28 July 1843, and on 7 August delivered his maiden speech in support of a motion by Mr Ewart for reduction of import duties.

A member who heard the speech described Bright as "about the middle size, rather firmly and squarely built, with a fair, clear complexion and an intelligent and pleasing expression of countenance.

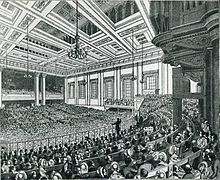

In London great meetings were held in Covent Garden Theatre, at which William Johnson Fox was the chief orator, but Bright and Cobden were the leaders of the movement.

The bad harvest and the potato blight drove him to the repeal of the Corn Laws, and at a meeting in Manchester on 2 July 1846 Cobden moved and Bright seconded a motion dissolving the league.

[5] According to the Oxford English Dictionary,[6] the first recorded use of the expression in its modern sense was by Bright in reference to the Reform Act 1867, which called for more democratic representation in Parliament.

When Lord John Russell brought forward his Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, Bright opposed it as "a little, paltry, miserable measure", and foretold its failure.

In a speech in favour of the government bill for a rate in aid (a tax on the prosperous parts of Ireland that would have paid for famine relief in the rest of that island) in 1849, he won loud cheers from both sides, and was complimented by Disraeli for having sustained the reputation of that assembly.

In this speech he demanded the enfranchisement of the working-class people because of their sheer number, and said that one should rejoice in open demonstrations rather than being confronted with "armed rebellion or secret conspiracy".

In 1868, Bright entered the cabinet of Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone as President of the Board of Trade, but resigned in 1870 due to ill health.

It may be that my hostility to the rebel party, looking at their conduct since your Government was formed six years ago, disables me from taking an impartial view of this great question.

If I could believe them honorable and truthful men, I could yield much—but I suspect that your policy of surrender to them will only place more power in their hands to war with greater effect against the unity of the 3 Kingdoms with no increase of good to the Irish people. ...

[23] At the famous meeting at the Committee Room 15, Liberal MPs who were not outright opponents of the idea of Irish self-government but who disapproved of the Bill, met to decide upon a course of action.

they will render a greater service by preventing the threatened dissolution than by compelling it ... a small majority for the Bill may be almost as good as its defeat and may save the country from the heavy sacrifice of a general election.

[25] Bright wrote to Chamberlain on 1 June that he was surprised at the meeting's decision because his letter "was intended to make it more easy for and your friends to abstain from voting in the coming division".

[29] The chairman of the National Liberal Federation, Sir B. Walter Foster, complained that Bright "probably did more harm in this election to his own party than any other single individual".

Lord George Hamilton recorded that when the government introduced the Criminal Law Amendment (Ireland) Bill in March 1887, which increased the authorities' coercive powers, the Liberal Party opposed it.

On the other hand if he, in order to avert Home Rule, voted for a procedure which was so contrary to his previous professions, the Coalition would receive a fresh source of strength and cohesion.

I believe he is the man who will break the iron rod of the South and set us free; for he has already fought for the liberty of the subject, and I cannot believe he will turn a deaf ear to our manifold sorrows.

On 27 November his son Albert wrote a letter to Gladstone in which he said his father "wishes me to write to you and tell you that "he could not forget your unvarying kindness to him and the many services you have rendered the country".

The Irish Nationalist MP Tim Healy wrote to Bright, wishing him a speedy recovery and "Your great services to our people can never be forgotten, for it was when Ireland had fewest friends that your voice was loudest on her side.

[43] In 1928, the Brooks-Bryce Foundation donated significant funds to the Princeton University Library for a collection of materials on the life and times of John Bright, in honour of the statesman.

He did more than any other man to prevent the intervention of this country (Britain) on the side of the South during the American Civil War, and he headed the reform agitation in 1867 which brought the industrial working class within the pale of the constitution.