John Brown (abolitionist)

[6][7] Brown said that in working to free the enslaved, he was following Christian ethics, including the Golden Rule,[8] and the Declaration of Independence, which states that "all men are created equal.

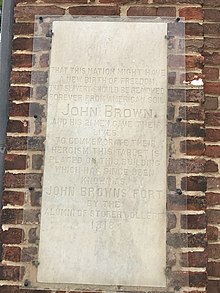

[11][12] The Harpers Ferry raid and Brown's trial, both covered extensively in national newspapers, escalated tensions that in the next year led to the South's long-threatened secession from the United States and the American Civil War.

[49] There is no known picture of her,[50] but he described Dianthe as "a remarkably plain, but neat, industrious and economical girl, of excellent character, earnest piety, and practical common sense".

[58] He bought 200 acres (81 hectares) of land, cleared an eighth of it, and quickly built a cabin, a two-story tannery with 18 vats, and a barn; in the latter was a secret, well-ventilated room to hide escaping slaves.

[57] For ten years, his farm was an important stop on the Underground Railroad,[60] during which, it is estimated to have helped 2,500 enslaved people on their journey to Canada, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development.

[86] In 1846, Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, as an agent for Ohio wool growers in their relations with New England manufacturers of woolen goods, but "also as a means of developing his scheme of emancipation".

[89] Brown made connections in Springfield that later yielded financial support he received from New England's great merchants, allowed him to hear and meet nationally famous abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, and included, after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the foundation of the League of Gileadites.

[88][89] Brown's personal attitudes evolved in Springfield, as he observed the success of the city's Underground Railroad and made his first venture into militant, anti-slavery community organizing.

[112] In the Battle of Black Jack of June 2, 1856, John Brown, nine of his followers, and 20 local men successfully defended a Free State settlement at Palmyra, Kansas, against an attack by Henry Clay Pate.

[113] In August, a company of over 300 Missourians under the command of General John W. Reid crossed into Kansas and headed toward Osawatomie, intending to destroy the Free State settlements there and then march on Topeka and Lawrence.

Brown prepared for battle, but serious violence was averted when the new governor of Kansas, John W. Geary, ordered the warring parties to disarm and disband, and offered clemency to former fighters on both sides.

Walker was the brother-in-law of Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, the secretary for the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, who introduced Brown to several influential abolitionists in the Boston area in January 1857.

[161] Some abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, opposed his tactics, but Brown dreamed of fighting to create a new state for freed slaves and made preparations for military action.

He refused the assistance of Silas Soule, a friend from Kansas who infiltrated the Jefferson County Jail one day by getting himself arrested for drunken brawling and offered to break him out during the night and flee northward to New York State and possibly Canada.

This text, written at Hauteville House on December 2, 1859, warned of a possible civil war: Politically speaking, the murder of John Brown would be an uncorrectable sin.

Morally speaking, it seems a part of the human light would put itself out, that the very notion of justice and injustice would hide itself in darkness, on that day where one would see the assassination of Emancipation by Liberty itself.The letter was initially published in the London News[dubious – discuss] and was widely reprinted.

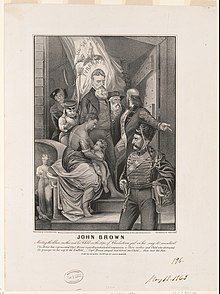

[206] Among the soldiers in the crowd were future Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, and John Wilkes Booth (the latter borrowing a militia uniform to gain admission to the execution).

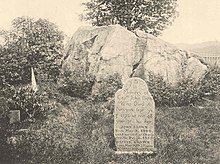

[212] Brown's desire, as told to the jailor in Charles Town, was that his body be burned, "the ashes urned", and his dead sons disinterred and treated likewise.

[219][221] In the North, large memorial meetings took place, church bells rang, minute guns were fired, and famous writers such as Emerson and Thoreau joined many Northerners in praising Brown.

[224] On December 14, 1859, the U.S. Senate appointed a bipartisan committee to investigate the Harpers Ferry raid and to determine whether any citizens contributed arms, ammunition or money to John Brown's men.

According to Frederick Douglass, "He was with the troops during that war, he was seen in every camp fire, and our boys pressed onward to victory and freedom, timing their feet to the stately stepping of Old John Brown as his soul went marching on.

In 1931, the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans erected a counter-monument, to Heyward Shepherd, a free black man who was the first fatality of the Harpers Ferry raid, claiming without evidence that he was a "representative of Negroes of the neighborhood, who would not take part".

Du Bois, Benjamin Quarles, and Lerone Bennett, Jr.[269] The connection between John Brown's life and many of the slave uprisings in the Caribbean was clear from the outset.

On La Amistad, Joseph Cinqué and approximately 50 other slaves captured the ship, slated to transport them from Havana to Puerto Príncipe, Cuba, in July 1839, and attempted to return to Africa.

Similar to the Haitian Revolution, the Seminole Wars, fought in modern-day Florida, saw the involvement of maroon communities, which although outnumbered by native allies were more effective fighters.

The 1940 film Santa Fe Trail, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, depicted Brown completely unsympathetically as a villainous madman and Massey plays him with a constant, wild-eyed stare.

[322] Massey, along with Tyrone Power and Judith Anderson, starred in the acclaimed 1953 dramatic reading of Stephen Vincent Benét's epic Pulitzer Prize-winning poem John Brown's Body (1928).

Behind him are Union and Confederate troops, with dead soldiers; a reference to the Bleeding Kansas period, which Brown was at the center of, and which was commonly seen to have been a dress rehearsal or a tragic prelude to the increasingly inevitable Civil War.

[336] The indictments, summons, sentences, bills of exception, and similar documents for Brown and his raiders are held by the Jefferson County Circuit Clerk, and have been digitized by West Virginia Archives and History.

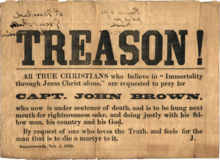

Among the missing material used at his trial as evidence of sedition were bundles of printed copies of his Provisional Constitution, prepared for the "state" Brown intended to set up in the Appalachian Mountains.