John Brown Farm State Historic Site

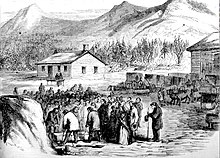

"[5] According to a 1935 visitor, "the site which so captivated John Brown on his first visit and held his interest to the end of his life is one of the most impressive in the Adirondacks.

The awe-inspiring mountains surrounding the spot look down on friendly valleys, lakes, hills, streams, homes, hamlets and villages.

The panorama stresses the power, majesty and eternal verities embodied in the towering peaks; calls attention to the peace, grandeur and solitude of the region; and deepens the feeling of man's weakness, finiteness and transitory abode on mother earth.

[2][8] It has been managed by the state since 1896; the grounds are open to the public on a year-round basis, and tours of the house are offered in the warmer months.

It had one good-sized room below, which answered pretty well for kitchen, dining-room, and parlour; also a pantry and two bedrooms; and the chamber furnished space for four beds—so that whenever a stranger or wayfaring man entered our gate, he was not turned away.

They lived in this house for two years, until Brown moved his family and his cattle to Akron, Ohio, where he needed to be while winding up his wool business.

These most beautiful and noble animals are the property of Mr. John Brown, of North Elba, and as a single entry, triumphantly bore away the palm.

"[13] "Our readers cannot have forgotten the strong impression produced by the appearance at the recent Fair, of the magnificent [Devons] of Mr. Brown of North Elba.

We are happy to Iearn that Mr. Brown, whose zeal and efficiency is most commendable, has, during the present autumn, added some fine animals to his herd.

Brown viewed the house he had built as a place not for himself—he lived there only 6 non-consecutive months—but for his wife and younger children, where they would be safe while he and his four oldest sons were in Kansas fighting slavery.

[15]: 17 According to a local historian, "besides the other inducements which this rough and bleak region offered him, he considered it a good refuge for his wife and younger children, when he should go on his campaign; a place where they would not only be safe and independent, but could live frugally, and both learn and practise those habits of thrifty industry which Brown thought indispensable in the training of children.

However, a visitor to the widowed Mary Brown in 1861 described the property as "a circular patch of about 60 acres (24 ha), cleared in the midst of the primeval forest, covered over with blackened stumps, and devoted to grass, buckwheat, oats and potatoes.

"[3] The 1861 visitor called it a cabin, "which has recently received the addition of another room, and the logs of the building covered with clap-boards through the liberality of his Boston friends".

Directly in front, apparently—perhaps from the thinness of the atmosphere—within two or three miles, but really much further off, looms up a rugged chain of the Adirondacks; broken, jagged[,] massive, and wonderfully picturesque.

Off the left stands, in solitary grandeur, the towering pyramid called "White Face"—deriving its name from the color of the rock, on its summit.

[5]The family graveyard, which Mary Brown exempted from the sale, is now part of the site, encircled by a modern iron fence.

John Brown was financially ruined[20]: 88 and had lost the family's home because of his disastrous 1849 business trip to England, meaning he could not repay the loans he had taken out to buy wool.

[22] The Timbuctoo experiment was a failure, as almost all the Blacks, save Lyman Epps, left within a few years; it was too cold and isolated, and clearing land and creating a farm is hard work.

Upon returning to Burlington, disapproval of his participation in Brown's funeral was so severe that he was forced to resign his pulpit, and his friends said that he had ruined his future, which turned out not to be true.

The one who was most directly involved in the Harpers Ferry Raid, Owen, 12 years later, after repeated attempts by a journalist, told his story once.

[8][53][54][55] In 1897, President McKinley was spending his summer in Plattsburgh, New York, and a special train to Lake Placid took him, Vice-President Hobart, Secretary of War Russell A. Alger, Secretary to the President John Addison Porter, and various Plattsburgh politicians, including Smith M. Weed, to the site for the dedication ceremony.

Kate Field, who is central to the site's history, had wanted to be buried here as well,[60] but this met with local opposition,[61] as did the erection of any monument to Brown other than the boulder.

In the early years especially, the Association would bring prominent speakers, such as attorney Clarence Darrow, Brown biographer Oswald Garrison Villard, and labor leader A. Philip Randolph.

[62] In 1935 there was a full program of activities and speakers, centering on the new "impressive heroic-sized statue of John Brown befriending a Negro boy", by Joseph Pollia.

[64][65] The plinth is of Ausable granite; the cement foundation, landscaping, walks, and rustic fences were the result of work by the Civilian Conservation Corps) (CCC).

Attendance was 2,000, including the mayor of Lake Placid, state historian Alexander C. Flick, and written greetings from Governor Lehman.

[67] The Lake Placid Justice O. Bryan Brewster of the New York Supreme Court gave that evening what the press called an "impressive and masterful address" on John Brown.

[69] After 1970, reports Amy Godine, the tone and goals of this annual pilgrimage shifted and softened, and failed to keep pace with the burgeoning civil rights movement.

[78] In 2017, the State University of New York at Potsdam held an archeology field school at the site, searching for artifacts linked to Brown.