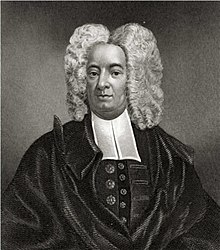

John Cotton (minister)

Many ministers were removed from their pulpits in England for their Puritan practices, but Cotton thrived at St. Botolph's for nearly 20 years because of supportive aldermen and lenient bishops, as well as his conciliatory and gentle demeanor.

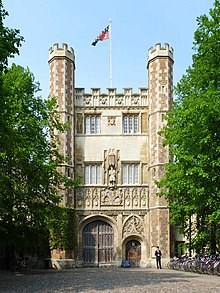

[15] One of the influences on Cotton's thinking while at Emmanuel was the teaching of William Perkins from whom he learned to be flexible, sensible, and practical, and how to deal with the political realities of being a non-conformist Puritan within a disapproving Church of England.

Even in his new subdued manner, he had a profound impact on those hearing his message; Cotton's preaching was responsible for the conversion of John Preston, the future Master of Emmanuel College and the most influential Puritan minister of his day.

"[24] Other inspirations to his theology include the Apostle Paul and Bishop Cyprian, and reformation leaders Zacharias Ursinus, Theodore Beza, Franciscus Junius (the elder), Jerome Zanchius, Peter Martyr Vermigli, Johannes Piscator, and Martin Bucer.

In the years before his immigration to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he gave advice to his former Cambridge student Reverend Ralph Levett, serving in 1625 as the private chaplain to Sir William and Lady Frances Wray at Ashby cum Fenby, Lincolnshire.

Cotton's colleagues were being summoned to the High Court for their Puritan practices, but he continued to thrive because of his supportive aldermen and sympathetic superiors, as well as his conciliatory demeanor.

[47] For this reason, he was upset to learn that Skelton's church at Naumkeag (later Salem, Massachusetts) had opted for such separatism and had refused to offer communion to newly arriving colonists.

[48] In particular, he was grieved to learn that William Coddington, his friend and parishioner from Boston (Lincolnshire), was not allowed to have his child baptized "because he was no member of any particular reformed church, though of the catholic" (universal).

[57] He contemplated going to Holland like many nonconformists, which allowed a quick return to England should the political situation become favorable and appeasing the sense that a "great reformation" was to take place soon.

[61] Eighteen months after his departure from England, Cotton wrote that his decision to emigrate was not difficult to make; he found preaching in a new land to be far preferable to "sitting in a loathsome prison.

[76] Williams had a reputation for both non-conformity and piety, although historian Everett Emerson calls him a "gadfly whose admirable personal qualities were mixed with an uncomfortable iconoclasm".

As a result, Endicott was barred from the magistracy for a year in May 1635, and Salem's petition for additional land was refused by the Massachusetts Court two months later because Williams was the minister there.

"[81] Williams was going to be shipped back to England by the Massachusetts magistrates, but instead he slipped away into the wilderness, spending the winter near Seekonk and establishing Providence Plantations near the Narragansett Bay the following spring.

Ministers and magistrates began sensing the religious unrest, and John Winthrop gave the first public warning of the ensuing crisis with an entry in his journal around 21 October 1636, blaming the developing situation on Hutchinson.

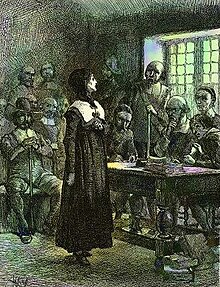

[86] On 25 October 1636, seven ministers gathered at the home of Cotton to confront the developing discord, holding a private conference which included Hutchinson and other lay leaders from the Boston church.

Familism is named for a 16th-century sect called the Family of Love; it teaches that a person can attain a perfect union with God under the Holy Spirit, coupled with freedom from both sin and the responsibility for it.

He discussed his own failure in not understanding the extent to which members of his congregation knowingly went beyond his religious views, specifically mentioning the heterodox opinions of William Aspinwall and John Coggeshall.

[103] During the heat of the controversy, Cotton considered moving to New Haven, but he first recognized at the August 1637 synod that some of his parishioners were harboring unorthodox opinions, and that the other ministers may have been correct in their views about his followers.

[109] In addition, Cotton continued an extensive correspondence with ministers and laymen across the Atlantic, viewing this work as supporting Christian unity similar to what the Apostle Paul had done in biblical times.

Despite the lopsided numbers, Cotton was interested in attending, though John Winthrop quoted Hooker as saying that he could not see the point of "travelling 3,000 miles to agree with three men.

"[118][119] Cotton changed his mind about attending as events began to unfold leading to the First English Civil War, and he decided that he could have a greater effect on the Assembly through his writings.

It was Cotton's attempt to persuade the assembly to adopt the Congregational way of church polity in England, endorsed by English ministers Thomas Goodwin and Philip Nye.

One of the most notorious of these sectaries was the zealous Samuel Gorton who had been expelled from both Plymouth Colony and the settlement at Portsmouth, and then was refused freemanship in Providence Plantation.

In the Massachusetts General Court, the magistrates sought the death penalty, but the deputies were more sympathetic to free expression; they refused to agree, and the men were eventually released.

He wrote, "It doth not a little grieve my spirit to heare what sadd things are reported dayly of your tyranny and persecutions in New-England as that you fyne, whip and imprison men for their consciences."

[148] During the final decade of his life, Cotton continued his extensive correspondence with people ranging from obscure figures to those who were highly prominent, such as Oliver Cromwell.

Robert Charles Anderson comments in the Great Migration series: "John Cotton's reputation and influence were unequaled among New England ministers, with the possible exception of Thomas Hooker.

[165] Literary scholar Everett Emerson calls Cotton a man of "mildness and profound piety" whose eminence was derived partly from his great learning.

[169] Among Cotton's descendants are Rev Nathaniel Thayer; U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Attorney General Elliot Richardson, actor John Lithgow, and clergyman Phillips Brooks.

[175] This was only modestly used in Massachusetts, but the code became the basis for John Davenport's legal system in the New Haven Colony and also provided a model for the new settlement at Southampton, Long Island.