John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hampshire.

While in England he was entertained by two of his powerful friends, Oliver Cromwell, who had become Lord Protector, and Sir Henry Vane, who occupied key positions in the government.

Following Cromwell's death, the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 and Vane's execution, Wheelwright returned to New England to become the minister in Salisbury, Massachusetts, where he spent the remainder of his life.

[2] After nearly ten years as vicar, Wheelwright was suspended in 1633 following his attempt to sell his Bilsby ministry back to its patron to get funds to travel to New England.

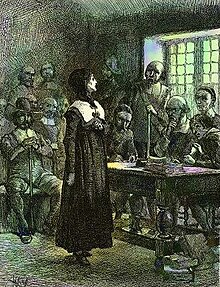

[2][7] During the year of his arrival, several of the Puritan ministers of Massachusetts had taken notice of the religious gatherings that his relative by marriage, Anne Hutchinson, had been holding at her house, and they also began having questions about the preaching of John Cotton whose Boston parishioners seemed to them to be harboring some theologically unsound opinions.

[13] Most of the New England Puritan ministers were adamantly opposed to these theological doctrines, seeing them as the cause of the violent and bloody ravages of the anabaptists in Germany during the Münster Rebellion of the 1530s.

On or shortly after 21 October 1636 he noted the rising disunity, but instead of pointing fingers at one of the godly ministers, he instead put the blame on Wheelwright's sister-in-law, writing, "One Mrs. Hutchinson, a member of the church at Boston, a woman of a ready wit and a bold spirit, brought over with her two dangerous errors: 1.

[21] These theological differences had begun to take their toll in the political aspects of the colony, and the Massachusetts governor, Henry Vane, who was a strong free grace advocate, announced his resignation to a special session of the deputies.

[21] While citing urgent matters back in England as being his reason for stepping down, when prodded, he broke down, blurting out his concern that God's judgment would "come upon us for these differences and dissensions".

[21] The members of the Boston church successfully induced Vane to withdraw his resignation, while the General Court began to debate who was responsible for the colony's troubles.

[17] Wheelwright then spoke in the afternoon, and while in the eyes of a lay person his sermon may have appeared benign and non-threatening, to the Puritan clergy it was "censurable and incited mischief".

It was the deputies who led the case against Wheelwright, and the charge they brought against him was "preaching on the Fast Day a Heretical and Seditious sermon, tending to mutiny and disturbance".

With the deputies then casting their votes, Wheelwright was declared guilty of "contempt & sedition" for having "purposely set himself to kindle and increase" bitterness within the colony.

[34] As the political aspects of the controversy intensified, Governor Vane was unable to prevent the Court from holding its next session in Newtown, where the orthodox party of most of the magistrates and ministers stood a better chance of winning if the elections were held away from Boston.

[40][41] Winthrop painted a picture of a peaceful colony before Wheelwright's arrival, and how after his fast-day sermon Boston men refused to join the Pequot War effort, Pastor Wilson was often slighted, and controversy arose in town meetings.

[51] In September 1642, while still in Exeter, an application for reconciliation was made on his behalf, to which the Bay Colony replied that he would be given safe conduct to return to Boston and petition the court.

[54] While this correspondence was taking place, another issue arose when, in early 1644, A Short Story of the Rise, reign and ruin of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines that infected the Churches of New England... was published in London.

He was deeply stung by the tenor of this work, coming at a time when he was making serious inroads into putting the events of the controversy behind him with the help and encouragement of some influential magistrates and ministers in the Bay Colony.

[58] Bell says of this work, "in tone and temper, it is incontestably superior to the Short Story, and, while devoted especially to the vindication of its author's doctrinal views, agreeably to the school of polemics then in vogue, it contains some key retorts upon his detractors, and indicates a mind trained to logical acuteness, and imbued with the learning of the times".

Wheelwright had probably long felt that some reparation was due for the attitudes conveyed in both the Short Story and in his release from banishment, and his Hampton townsmen were likely well aware of this.

[63] In 1658, Edward Cole of London published Wheelwright's A Brief and Plain Apology, whose lengthy subtitle read "Wherein he doth vindicate himself, From al those Errors, Heresies, and Flagitious Crimes, layed to his charge by Mr. Thomas Weld, in his short story, And further Fastened upon him by Mr. Samuel Rutherford in his Survey of Antinomianisme".

[64] Wheelwright's purpose in publishing this work was so that his innocence and the unfairness of his trial be recognized, and that "his views on the process by which the saved acquired grace be accepted as correct, even orthodox".

[71] The writing of Wheelwright's Brief and Plain Apology may have commenced as early as 1644 when Short Story was published, but based on datable events the last part was written after his vindication by the Massachusetts court in 1654.

In the first half of this work, Wheelwright refers to the author of Short Story as a singular person, clearly thinking that Thomas Weld had written the entire piece.

[77] Wheelwright's position at the church in Hampton had, as expected, been filled during his absence, but he was quickly called by residents of the neighboring town of Salisbury to be their pastor, and on 9 December 1662, when 70 years old, he was installed there.

[78] Probably the most noteworthy event of his tenure in Salisbury occurred very late in his life when Major Robert Pike, a layman and prominent member of his church, collided with him during the winter of 1675 to 1676.

In the spring of 1677 disaffected members of the church and town petitioned the court that Wheelwright was the cause of the disturbance, and that his preaching had a tendency to pit one person against another, and requested he be removed from the ministry.

[84] In October 1677, Wheelwright sold his property in Lincolnshire, (purchased of Francis Levett, gentleman) to his son-in-law Richard Crispe, the husband of his youngest daughter, Sarah.

Sometime before his death, Governor Bell acknowledged the sequence of events and that the deed was an ingenious fabrication, and stated this in an undated letter to the New England Historical and Genealogical Society.

In Massachusetts he was to blame for much of the temper and spirit which he displayed, when "by a more moderate carriage he might have mitigated the bitterness of the strife ..."[89] However, Bell found him to be neither intractable nor unforgiving, and called him notably energetic, industrious and courageous.