John Dooly

Everything known about Patrick Dooly's life parallels that of the archetypical traditional and historical southern Scots-Irish frontiersman, as portrayed in works like David Hackett Fischer's Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America.

As with many other Virginians, Patrick moved to the South Carolina frontier sometime between August 2, 1764, and July 2, 1765, according to land grant records, likely in search of unclaimed property to develop for sale to later settlers and for security from conflicts with the natives.

(n6) A few years later, an adult John Dooly traveled hundreds of miles from the Ninety Six frontier to Charleston, the seat of the only local government body in South Carolina, to go through the legal formalities to settle his father's insignificant estate.

He and his fellow locally ordained clergymen created their own revolution in filling a long-standing demand for ministers in the backcountry where the need could not be met by the traditional religions that required men like Woodmason to obtain formal training.

(n12) The North Carolina Regulator War that broke out among backcountry people and literally at John Dooly's very door in Ninety Six in the late 1760s serves as an even greater example of what historian Jack Greene described as settlers on the southern frontier desiring "improvement" in the form of courthouses, schools, towns, and an environment conducive to trade and investment.

Civil affairs on the South Carolina frontier proved so confused that Dooly's father, for example, once received a grant of land that appears in various colonial records as being in three different counties, none of which had a courthouse or any other form of local government.

Charles Woodmason, a Regulator supporter, denounced what he viewed as a morally uninhibited culture in frontier South Carolina, but he also saw the growth of its population as dynamic (he claimed that ninety-four out of every one hundred brides in ceremonies he performed were obviously with child) and that its economy grew as fast.

Thousands of frontiersmen like Dooly participated in that colonial revolution and demanded from South Carolina's government (what historian Hugo Bicheno termed as "Tidewater Rats" and "wealthy coastal slavocrats" with a "psedo-aristiocratic social structure") the right to the benefits of rule of law in the backcountry.

As with almost all of the frontiersmen directly affected by that successful and sometimes violent popular uprising to force the establishment of courts on the frontier, Dooly's name appears on none of the surviving records, including on the list of pardons granted to one hundred and twenty Regulator leaders.

In 1773, Georgia royal governor James Wright preempted this plan and persuaded the Creek and Cherokee nations to give up what he named the Ceded Lands, some 1,500,000 acres (6,100 km2) that would greatly expand the northwest border of St. Paul Parish.

At that time, naturalist William Bartram passed through this area twice and would write a description that reads like a biblical prophecy of its coming troubles: The day's progress was agreeably entertaining, from the novelty and variety of objects and views; the wild country now almost depopulated, vast forests, expansive plains and detached groves; then chains of hills whose gravelly, dry, barren summits present detached piles of rocks, which delude and flatter the hopes and expectations of the solitary traveller, full sure of hospitable habitations; heaps of white, gnawed bones of the ancient buffaloe, elk and deer, indiscriminately mixed with those of men, half grown over with moss, altogether exhibit scenes of uncultivated nature, on reflection, perhaps, rather disagreeable to a mind of delicate feelings and sensibility, since some of these objects recognize past transactions and events, perhaps not altogether reconcilable to justice and humanity.

When raiding parties of disaffected Creeks protested the loss of the Ceded Lands by attacking its settlements and defeating the St. Paul's Parish militia in 1773-1774, Wright used diplomacy with pro-British leader Emistisiguo to end the crisis.

Opposing the largely coastal opposition to British policies in 1774, a delegation from the frontier (that included Dooly) tried to present Georgia's rebel provincial congress with a letter of protest against the growing political discontent in the colony.

As a result, John Dooly, Elijah Clarke, George Wells, Barnard Heard, and many other later Whig leaders, joined hundreds of their neighbors in exercising their rights as Englishmen to sign and publish petitions in support of British rule in the colony's newspaper, the Georgia Gazette.

A formal morning report of Dooly's militia regiment in 1779 shows that it was a sophisticated organization with quartermasters, musicians, boatmen, blacksmiths, cow drivers, butchers, wagon masters, and deputy commissaries.

John Coleman, formerly of Virginia and a wealthy leader in the Ceded Lands, also opposed the petition and even wrote to McIntosh complaining that "Gentlemen of Abilities, whose characters are well established, are the only persons objected to, to govern and manage in State affairs with us.

As he later related to a British writer, however, Hamilton discovered that "although many of the people came in to take the oath of allegiance, the professions of a considerable number were not to be depended upon; and that some came in only for the purpose of gaining information on his strength and future designs.

During the previous summer's Native American troubles, more than five hundred South Carolina militiamen had come to Wilkes County's aid under Gen. Andrew Williamson, originally an illiterate cattle driver from near Dooly's former home at Ninety Six who had risen to wealth and prominence before the war.

Dooly had a deposition taken by justice of the peace Stephen Heard wherein a William Millen had described meeting a Loyalist leader identified as James Boyd, when the latter had recently been at Wrightsborough seeking guides to South Carolina.

Boyd and his ad hoc regiment of North and South Carolina Loyalists camped at a cowpen or small farm in a meadow atop a steep hill in a bend of swampy Kettle Creek, less than a mile from Carr's Fort and hardly much further from Wrightsborough, on Sunday morning February 14.

The Native American with Alexander McGillivray met defeat at Rocky Comfort Creek on March 29 at the hands of militiamen under colonels Leroy Hammond of South Carolina and Benjamin Few of Georgia.

These professional soldiers from the fortified garrisons in New York and East Florida continued to win the formal battles only to lose the war to a widespread popular resistance that won by keeping the insurgency going indefinitely.

Even the survivors of Kettle Creek and Taitt's warriors who reached Savannah proved to be of little military value to the king George iii Any such ambitions for a restored British rule in America represented the "past;" John Dooly and his allies had become the powers of the "present."

Historian Robert M. Weir has pointed out that the Regulator rebellion had taught the frontiersmen that leaders who failed to act against persons perceived as public enemies risked losing credibility with their followers.

Much of Georgia had become a no-man's land between the opposing factions where guerrillas and apolitical gangs acted as destructive brigands who took advantage of the vacuum of civil law, much like South Carolina's frontier had been before the Regulators.

William Manson, a Scotsman whose foreign settlement project in the Ceded Lands had failed because of the Revolution, arrived in Wilkes County to accept the surrender of John Dooly and four hundred of the Georgia militia on a ridge outside the town of Washington in late June 1780.

Rescued and reinforced by South Carolina Loyalist provincials, the long-suffering Tories and Native Americans then began a campaign of retaliation as they went from being the oppressed to the avenged, starting with the executions of men captured during Clarke's attack on the Augusta garrison.

On July 24, 1782, in his final act for his British patrons, he died in hand-to-hand combat with Gen. Anthony Wayne while leading a Creek war party and Loyalists in a desperate but successful effort to break through to the garrison at Savannah.

(n58) Even as a symbolic expression of creating local government, like so much of the British policy during the American Revolution, this action came as far too little and much too late for anything more than demonstrating that the civil progress on the frontier existed as something greater than even the war with which it happened to coexist.

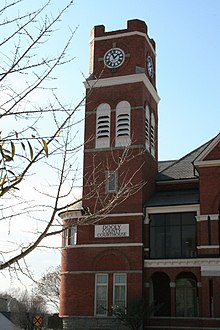

(n63) He quite likely used the considerable influence he later gained as an important judge and politician, along with John Dooly's notoriety as published in McCall's history, to encourage the state legislature to create a county named for his father in 1821.