British Raj

The proclamation stated that 'We disclaim alike our Right and Desire to impose Our Convictions on any of Our Subjects';[36] demonstrating official British commitment to abstaining from social intervention in India.

Although famines were not new to the subcontinent, these were particularly severe, with tens of millions dying,[citation needed] and with many critics, both British and Indian, laying the blame at the doorsteps of the lumbering colonial administrations.

[48] It was, however, Viceroy Lord Ripon's partial reversal of the Ilbert Bill (1883), a legislative measure that had proposed putting Indian judges in the Bengal Presidency on equal footing with British ones, that transformed the discontent into political action.

Prominent among the extremists was Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who attempted to mobilise Indians by appealing to an explicitly Hindu political identity, displayed, for example, in the annual public Ganapati festivals that he inaugurated in western India.

[55] His agenda included the creation of the North-West Frontier Province; small changes in the civil services; speeding up the operations of the secretariat; setting up a gold standard to ensure a stable currency; creation of a Railway Board; irrigation reform; reduction of peasant debts; lowering the cost of telegrams; archaeological research and the preservation of antiquities; improvements in the universities; police reforms; upgrading the roles of the Native States; a new Commerce and Industry Department; promotion of industry; revised land revenue policies; lowering taxes; setting up agricultural banks; creating an Agricultural Department; sponsoring agricultural research; establishing an Imperial Library; creating an Imperial Cadet Corps; new famine codes; and, indeed, reducing the smoke nuisance in Calcutta.

The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision took the form predominantly of the Swadeshi ("buy Indian") campaign led by two-time Congress president, Surendranath Banerjee, and involved boycott of British goods.

[69] In the 1916 Lucknow session of the Congress, Tilak's supporters were able to push through a more radical resolution which asked for the British to declare that it was their "aim and intention ... to confer self-government on India at an early date".

[73] Besant, for her part, was also keen to demonstrate the superiority of this new form of organised agitation, which had achieved some success in the Irish home rule movement, over the political violence that had intermittently plagued the subcontinent during the years 1907–1914.

Their propaganda also turned to posters, pamphlets, and political-religious songs, and later to mass meetings, which not only attracted greater numbers than in earlier Congress sessions, but also entirely new social groups such as non-Brahmins, traders, farmers, students, and lower-level government workers.

Soon, under pressure from the Viceroy in Delhi who was anxious to maintain domestic peace during wartime, the provincial government rescinded Gandhi's expulsion order, and later agreed to an official enquiry into the case.

The following year Gandhi launched two more Satyagrahas—both in his native Gujarat—one in the rural Kaira district where land-owning farmers were protesting increased land-revenue and the other in the city of Ahmedabad, where workers in an Indian-owned textile mill were distressed about their low wages.

[77] In 1916, in the face of new strength demonstrated by the nationalists with the signing of the Lucknow Pact and the founding of the Home Rule leagues, and the realisation, after the disaster in the Mesopotamian campaign, that the war would likely last longer, the new viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, cautioned that the Government of India needed to be more responsive to Indian opinion.

The principal of "communal representation", an integral part of the Minto–Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.

[80] In 1917, as Montagu and Chelmsford were compiling their report, a committee chaired by a British judge, Sidney Rowlatt, and was tasked with investigating "revolutionary conspiracies", with the unstated goal of extending the government's wartime powers.

[82] Returning war veterans, especially in the Punjab, created a growing unemployment crisis,[83] and post-war inflation led to food riots in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal provinces,[83] a situation that was made only worse by the failure of the 1918–19 monsoon and by profiteering and speculation.

[81] Although the bills were authorised for legislative consideration by Edwin Montagu, they were done so unwillingly, with the accompanying declaration, "I loathe the suggestion at first sight of preserving the Defence of India Act in peacetime to such an extent as Rowlatt and his friends think necessary.

Again the outbreak of war strengthened them, in the face of the Quit India movement the revenue collectors had to rely on military force and by 1946–47 direct British control was rapidly disappearing in much of the countryside.

[91] However, it divided the electorate into 19 religious and social categories, e.g., Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Depressed Classes, Landholders, Commerce and Industry, Europeans, Anglo-Indians, etc., each of which was given separate representation in the Provincial Legislative Assemblies.

He proclaimed the Two-Nation Theory,[101] stating at Lahore on 23 March 1940: [Islam and Hinduism] are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but are, in fact, different and distinct social orders and it is a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality ...

In addition, heavy British spending on munitions produced in India (such as uniforms, rifles, machine-guns, field artillery, and ammunition) led to a rapid expansion of industrial output, such as textiles (up 16%), steel (up 18%), and chemicals (up 30%).

Earlier, at the end of the war in 1945, the colonial government had announced the public trial of three senior officers of Bose's defeated Indian National Army who stood accused of treason.

With the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence.

[145] The last vestige of the Mughal Empire in Delhi which was under Company authority prior to the advent of British Raj was finally abolished and seized by the Crown in the aftermath of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 for its support to the rebellion.

Extensive irrigation systems were built, providing an impetus for switching to cash crops for export and for raw materials for Indian industry, especially jute, cotton, sugarcane, coffee and tea.

The British imposed "free trade" on India, while continental Europe and the United States erected stiff tariff barriers ranging from 30% to 70% on the importation of cotton yarn or prohibited it entirely.

[169] According to The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, TISCO became the leading iron and steel producer in India, and "a symbol of Indian technical skill, managerial competence, and entrepreneurial flair".

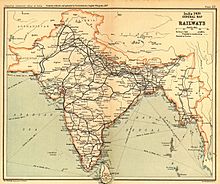

[176] After the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, and subsequent Crown rule over India, the railways were seen as a strategic defense of the European population, allowing the military to move quickly to subdue native unrest and protect Britons.

[citation needed] With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to making munitions; the locomotives, rolling stock, and track of some entire lines were shipped to the Middle East.

[191] He argues the British takeover did not make any sharp break with the past, which largely delegated control to regional Mughal rulers and sustained a generally prosperous economy for the rest of the 18th century.

[204] Britain's Sir Ronald Ross, working in the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta, finally proved in 1898 that mosquitoes transmit malaria, while on assignment in the Deccan at Secunderabad, where the Centre for Tropical and Communicable Diseases is now named in his honour.