John Edward Brownlee

Born in Port Ryerse, Ontario, he studied history and political science at the University of Toronto's Victoria College before moving west to Calgary to become a lawyer.

He was closely involved in its most important activities, including efforts to better the lot of farmers living in Alberta's drought-ridden south, divest itself of money-losing railways, and win jurisdiction over natural resources from the federal government.

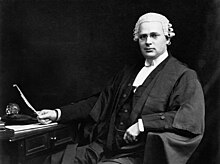

[13] He fast gained a reputation as a competent instructor: his old work ethic served him well, and his seriousness, cool blue-grey eyes, and six foot four frame combined to give him an impressive presence.

[17] Besides these chosen subjects, he was required to study mathematics, biology, English literature, composition, Latin, and two additional languages—despite having some knowledge of French, he chose German and Hebrew.

[19] As he became more involved in extracurricular pursuits, these grades fell; after his fourth and final year, he graduated with III Class Honours, leaving him out of the top tier of students.

Christmas morning 1923, the Brownlee boys awoke to find footprints of coal dust leading from the fireplace to the stairs and a handwritten note from Santa Claus apologizing for the mess and explaining that he had been searching for one of his reindeer.

[36] Brownlee and Victoria classmate Fred Albright resolved to go west; after narrowing the choice to either Calgary or Vancouver, the former was selected on the basis that its legal community was less established, and it offered better prospects to young lawyers without significant capital.

[41] On the outbreak of World War I, Brownlee did not enlist; his biographer, Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, speculates that this may have been because of his eyesight, but notes that he did not involve himself in patriotic fundraising or volunteer work and questions whether he "completely shared the values and ideals of his generation".

[40] One of Muir, Jephson and Adams' major clients was a new agricultural lobby organization called the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA), and it was with this group that Brownlee began to work most closely.

[46] Brownlee was heavily involved at both meetings, fielding questions from shareholders about legal ramifications and serving on ad hoc subcommittees to study aspects of the proposal.

Though most of his legal work was for the AFCEC and then the UGG, Brownlee also made contact with leaders of the UFA proper, including William Irvine, Irene Parlby, Herbert Greenfield, and, most importantly, Henry Wise Wood.

[66] His training in business and law, unique in the UFA caucus, gave him a central role in most of the government's initiatives;[67] he also led the defense against attacks from the Liberal opposition, and eventually became responsible for setting the agenda for cabinet meetings.

[74] As attorney-general, Brownlee was Alberta's chief negotiator in these efforts,[74] and met frequently with representatives of Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.

[67] The 1922 murder of Alberta Provincial Police constable Steve Lawson by bootleggers Emil Picariello and Florence Lassandro, for which they were hanged, helped turn public opinion against it.

[87] Brownlee's first challenges as premier were similar to those he had faced as attorney-general: winning control of Alberta's natural resources, selling the money-losing railways, and balancing the provincial budget.

[104] Despite this success, Brownlee continued to advocate austerity,[105] and tried unsuccessfully to persuade the federal government to assume a greater share of the costs of new social programs, such as the old age pension.

[113] The Alberta Wheat Pool (AWP) guaranteed its members a minimum price of $1.00 per bushel (itself not enough for many farmers to earn a living), and it found itself facing ruination.

Brownlee was concerned that such guarantees would encourage lenders to make loans at higher interest rates, with the knowledge that the provincial government would pay them if the farmers defaulted.

[117] Further weakening Brownlee's control of the situation, the UFA, around this time, took a sharp left-ward turn, as Robert Gardiner replaced retiring Henry Wise Wood as president of the provincial body.

[127] During the Great Depression's early years, Calgary schoolteacher and evangelist William Aberhart began to preach a version of C. H. Douglas's social credit economic theory.

[128] Brownlee believed that Aberhart's proposals would be both unconstitutional (if implemented by a provincial government, which did not have control over monetary policy) and ineffective (since they would not create markets for Alberta's agricultural products).

He returned to the public eye with a speech to the January 1935 UFA convention attacking Aberhart's plans to implement social credit in Alberta alone: "I would impress you that nothing but disillusionment, loss of hope and additional despair can follow any attempt to inaugurate a system of that kind, because the Province has no jurisdiction in these matters.

[144] By 1940, Brownlee had restored his career to it position before he entered politics: his firm counted a number of major agricultural companies among its clients, and the UGG too brought him considerable work.

In 1941, Brownlee travelled to Ottawa to express the UGG's case; there he collaborated with O. M. Biggar, representing the private grain companies in the form of the North-West Line Elevators Association (NLEA), who also objected to the pools' exemption, on a joint brief to the Minister of National Revenue.

[156] Though UGG shareholders subjected him to vigorous questioning, he held firm and the controversy died down after he gave a series of radio addresses in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

The federal government, which had negotiated the agreement, offered to supplement the British payments by $65 million, a sum large enough to raise the ire of eastern Canadians but too small to placate western farmers.

He advocated a policy of full employment, and emphasized that jobs had to be meaningful rather than "put[ting] men to work building roads like coolies in China when machines can do it better".

He criticized the government-imposed wartime ceiling on wheat prices, of $1.25 per bushel, as forcing farmers to shoulder an unfair burden of a national crisis, as they had during the depression.

The UFA awarded him an honorary life membership, and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker appointed him to the National Productivity Council, though ill health prevented him from participating after its inaugural March 1961 meeting.

[179] In 1980, the Edmonton Journal wrote, "The lasting political estate left by former Premier John Brownlee has made Alberta what it is today, one of Canada's wealthiest provinces fuelled by billions of dollars in oil and gas royalties.