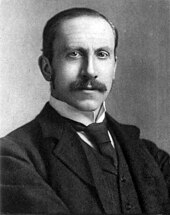

John Harrison Clark

John Harrison Clark III or Changa-Changa (10 May 1860 – 9 December 1927) was an Anglo-South African explorer and adventurer who effectively ruled much of what is today southern Zambia from the early 1890s to 1902.

[7] When Clark arrived about three decades later, the Portuguese still maintained a boma (fort) called Zumbo on the opposite bank of the Luangwa,[4] but the surrounding country was largely wild and out of the control of any government.

[8] Slave-raiding was rife along the Zambezi River, with gangs of Arab, Portuguese and mixed Chikunda-Portuguese ethnicity competing for the capture of local Baila and Batonga people for use as slaves.

[1] According to a story told by an acquaintance, Harry Rangeley, and partly corroborated by Alexander Scott in the Central African Post in 1949, he became chief by virtue of winning a battle.

[10] As chief, Clark secured his authority with his army of Senga warriors, defined and collected "taxes" and oversaw the activities of foreign traders in the area.

The most prominent trans-river clash came when Clark demonstrated the strength of his army by overpowering the fort's garrison, pulling down the Portuguese flag and running up the Union Jack in its place.

The BSAC sought to further expand its influence north of the Zambezi, and to that end regularly sent expeditions into what was dubbed North-Eastern Rhodesia to negotiate concessions with local rulers and found settlements.

[17] In 1896, Major Deare led one such expedition north from the main seat of Company administration, Fort Salisbury, to meet with the Ngoni chief Mpezeni, who ruled to the east of Harrison Clark.

This message, written in English and signed "Changa-Changa, Chief of the Mashukulumbwe"—the name John Harrison Clark was given in the body of the letter—said that its author had heard of a white man being entertained recently by Mpezeni, and wished to provide the same hospitality at Algoa.

He negotiated concessions with two neighbouring chiefs, Chintanda and Chapugira, each of whom signed over the mining and labour rights for his respective territory in return for a specified fee whenever Clark wished to use them.

Also providing a cursory description of gold mining prospects in the region, Clark criticised the actions of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Warton, who was in the vicinity representing the North Charterland Exploration Company, a BSAC subsidiary.

[20] Clark wrote to the Company again on 12 April 1899, once more attaching copies of his concessions, with an offer to supply the BSAC settlements in Southern Rhodesia with contract labourers taken from among his neighbouring chiefs' populations.

The chiefs had agreed to provide workers on contracts lasting six months, but Clark wrote that he could attempt to supply labour all year round if the Company wished.

[21] On 14 April 1899, Chief Chintanda gave a BSAC commissioner at Mazoe, Southern Rhodesia a statement in which, among other things, he asserted that Clark had been claiming to be a Company official and had been collecting tariffs such as hut tax under that pretence for at least two years.

The situation was complicated when, after a month's perusal, the company's lawyers resolved that the courts in Salisbury and Bulawayo held no jurisdiction outside Southern Rhodesia and therefore could not hear any case brought against Clark.

[23] On 4 July 1899, Arthur Lawley, the company's administrator in Matabeleland, wrote to Cape Town to report the situation to the resident High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Alfred Milner.

[25] On 24 August 1899, Sub-Inspector A M Harte-Barry of the British South Africa Police interviewed Chief Mubruma, who corroborated much of what Chintanda had said regarding Clark's claims to represent the company.

[29] Clark reluctantly accepted the compensation when he realised that to challenge the BSAC he would have to travel a great distance, possibly to England, and invest heavily in a court case he would probably lose.

[27] Retaining "Changa-Changa" as a nickname, he helped to develop various businesses and events, acted as a partner in the first licensed brewery in Northern Rhodesia (alongside Lester Blake-Jolly), and became "one of the pillars of society in the Broken Hill of those days", according to Spurr.

[31] He owned one of the first automobiles in Northern Rhodesia—a dark green Ford Model T.[31] According to Brelsford, the elderly Harrison Clark remained highly respected among the indigenous people and was sometimes called upon to settle disputes.