John Romanides

In 1968 he was appointed as tenured professor of Dogmatic Theology at the University of Thessaloniki, Greece, a position he held until his retirement in 1982.

Romanides belonged to the "theological generation of the 1960s", which pleaded for a "return to the Fathers", and led to "the acute polarization of the East-West divide and the cultivation of an anti-Western, anti-ecumenical sentiment.

[9]His research on dogmatic theology led him to the conclusion of a close link between doctrinal differences and historical developments.

Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Assyrian Church of the East, which together make up Eastern Christianity, contemplate that the introduction of ancestral sin into the human race affected the subsequent environment for humanity, but never accepted Augustine of Hippo's notions of original sin and hereditary guilt.

[13] Eastern Orthodox theologians John Romanides and George Papademetriou say that some of Augustine's teachings were actually condemned as those of Barlaam the Calabrian at the Hesychast or Fifth Council of Constantinople 1351.

[note 6] Theoria, contemplatio in Latin, as indicated by John Cassian,[18] meaning vision of God, is closely connected with theosis (divinization).

[note 11] The Greek Old Calendarist,[21] Archimandrite [later Archbishop] Chrysostomos González of Etna, CA, criticized Romanides' criticism of Augustine:[note 12] In certain ultra-conservative Orthodox circles in the United States, there has developed an unfortunate bitter and harsh attitude toward one of the great Fathers of the Church, the blessed (Saint) Augustine of Hippo (354–430 A.D.).

Not a few writers and spiritual aspirants have been disturbed by this trend.According to Romanides, the theological concept of hell, or eternal damnation is expressed differently within Eastern and Western Christianity.

[8][note 14] Aristotle Papanikolaou [26] and Elizabeth H. Prodromou [27] wrote in their book Thinking Through Faith: New Perspectives from Orthodox Christian Scholars that for the Orthodox the theological symbols of heaven and hell are not crudely understood as spatial destinations but rather refer to the experience of God's presence according to two different modes.

According to Iōannēs Polemēs, Theophanes believed that, for sinners, "the divine light will be perceived as the punishing fire of hell".

[36] "The circumstances that rise before us, the problems we encounter, the relationships we form, the choices we make, all ultimately concern our eternal union with or separation from God.

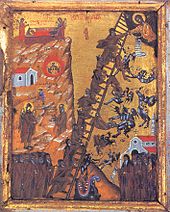

"[41] The practice of ascetic prayer called hesychasm in the Eastern Orthodox Church is centered on the enlightenment, deification (theosis) of man.

[2] Kalaitzidis further notes that Romanides' post-1975 theology has "furnished a convenient and comforting conspiratorial explanation for the historical woes of Orthodoxy and Romiosyne", but is "devoid of the slightest traces of self-criticism, since blame is always placed upon others".

[56] James L. Kelley's recent article has argued that Kalaitzidis's concern that Orthodox theologians engage in "self-criticism" is a ploy to engineer a "development of Orthodox doctrine" so that, once the Orthodox place some of the blame on themselves for "divisions of Christian groups", they will adjust the teachings of Orthodoxy to suit the ecumenist agenda (see James L. Kelley, "Romeosyne" According to John Romanides and Christos Yannaras: A Response to Pantelis Kalaitzidis [Norman, OK: Romanity Pres, 2016]).