Theosis (Eastern Christian theology)

As a process of transformation, theosis is brought about by the effects of catharsis (purification of mind and body) and theoria ('illumination' with the 'vision' of God).

[2] Byzantine Christians consider that "no one who does not follow the path of union with God can be a theologian"[3] in the proper sense.

Instead it is based on applied revelation (see gnosiology), and the primary validation of a theologian is understood to be a holy and ascetical life rather than intellectual training or academic credentials (see scholasticism).

[2] Athanasius of Alexandria wrote, "He was incarnate that we might be made god" (Αὐτὸς γὰρ ἐνηνθρώπησεν, ἵνα ἡμεῖς θεοποιηθῶμεν).

Thus the doctrine avoids pantheism while partially accepting Neoplatonism's terms and general concepts,its substance (see Plotinus).

Irenaeus explained this doctrine in the work Against Heresies, Book 5, Preface: "the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, Who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself."

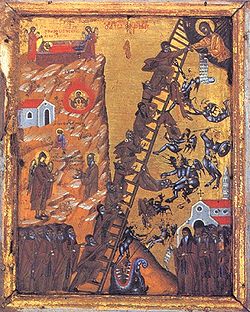

Of the monastic tradition, the practice of hesychasm is most important as a way to establish a direct relationship with God.

It is considered that no one can reach theosis without an impeccable Christian living, crowned by faithful, warm, and, ultimately, silent, continuous Prayer of the Heart.

[12] The "doer" in deification is the Holy Spirit, with whom the human being joins his will to receive this transforming grace by praxis and prayer, and as Gregory Palamas teaches, the Christian mystics are deified as they become filled with the Light of Tabor of the Holy Spirit in the degree that they make themselves open to it by asceticism (divinization being not a one-sided act of God, but a loving cooperation between God and the advanced Christian, which Palamas considers a synergy).

[15] Yet, recent theological discourse has seen a reversal of this, with Bloor drawing upon Western theologians from an array of traditions, whom, he claims, embrace theosis/deification.

The doctrine of Gregory Palamas won almost no following in the West,[18] and the distrustful attitude of Barlaam in its regard prevailed among Western theologians, surviving into the early 20th century, as shown in Adrian Fortescue's article on hesychasm in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia.

[20] In the same period, Edward Pace's article on quietism indicated that, while in the strictest sense quietism is a 17th-century doctrine proposed by Miguel de Molinos, the term is also used more broadly to cover both Indian religions and what Edward Pace called "the vagaries of Hesychasm", thus betraying the same prejudices as Fortescue with regard to hesychasm;[21] and, again in the same period, Siméon Vailhé described some aspects of the teaching of Palamas as "monstrous errors", "heresies" and "a resurrection of polytheism", and called the hesychast method for arriving at perfect contemplation "no more than a crude form of auto-suggestion".

[a][23] The twentieth century saw a remarkable change in the attitude of Roman Catholic theologians to Palamas, a "rehabilitation" of him that has led to increasing parts of the Western Church considering him a saint, even if uncanonized.

[25] According to G. Philips, the essence–energies distinction is "a typical example of a perfectly admissible theological pluralism" that is compatible with the Roman Catholic magisterium.

[25] Jeffrey D. Finch claims that "the future of East–West rapprochement appears to be overcoming the modern polemics of neo-scholasticism and neo-Palamism".

Barlaam – and also medieval Latin tradition – tends to understand this created habitus as a condition for and not a consequence of grace.