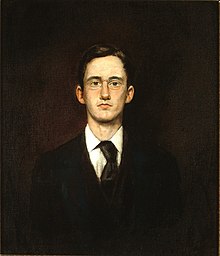

John Sloan

[3] In the spring of 1888, his father experienced a mental breakdown that left him unable to work, and Sloan became responsible, at the age of sixteen, for the support of his parents and sisters.

In 1890, the offer of a higher salary persuaded Sloan to leave his position to work for A. Edward Newton, a former clerk for Porter and Coates who had opened his own stationery store.

[6] In April 1904, he and Dolly moved to New York City and found quarters in Greenwich Village where he painted some of his best-known works, including McSorley's Bar, Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street, and Wake of the Ferry.

Sloan organized a touring exhibition of the paintings from that show that traveled to several cities from Newark to Chicago and elicited considerable discussion in the press about less academic approaches to art and new definitions of acceptable subject matter.

Spanning the period from 1906 to early 1913, the diary soon grew beyond its initial purpose, and its publication in 1965 supplied researchers with a detailed chronicle of Sloan's activities and interests and a portrait of the pre-war art world.

John Sloan became the art editor of The Masses with the December 1912 issue[14] and contributed powerful anti-war and anti-capitalist drawings to other socialist publications as well, such as the Call and Coming Nation.

In 1913, Sloan painted a two-hundred-foot backdrop for the Paterson Strike Pageant, a controversial work of performance art and radical politics organized by activist John Reed and philanthropist Mabel Dodge.

The play, a benefit staged for the striking silk mill workers of Paterson, New Jersey, took place in Madison Square Garden and incorporated over 1,000 participants.

Sloan has been called "the premier artist of the Ashcan School who painted the inexhaustible energy and life of New York City during the first decades of the twentieth century".

[18] For Sloan, exposure to the European modernist works on view in the Armory Show initiated a gradual move away from the realist urban themes he had been painting for the previous ten years.

[19] In 1914–15, during summers spent in Gloucester, Massachusetts, he painted landscapes en plein air in a new, more fluid and colorful style influenced by Van Gogh and the Fauves.

[22] As a result of his time in the Southwest, he and Dolly developed a strong interest in Native American arts and ceremonies and, back in New York, became advocates of Indian artists.

Sloan worked several jobs in draughtsmanship, etching, and commercial artwork before he attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied briefly under Thomas Anshutz.

But by 1894 he had begun attracting attention with decorative illustrations in a new style related to the poster movement; these works combine the influences of European artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, including Walter Crane, and reveal Sloan's study of Botticelli and Japanese prints.

In 1893, Sloan and Glackens became regulars at a weekly "open house" at Henri's studio, where he encouraged the young men to read Whitman and Emerson and led discussions of such books as George Moore's Modern Painting and William Morris Hunt's Talks on Art.

[28] Henri believed in the need to create a new, less genteel American art that spoke more immediately to the spirit of the age, an outlook that found ready adherents in Sloan and Glackens.

As someone who painted city crowds and tenement rooms, shop girls and streetwalkers, charwomen and hairdressers, Sloan is one of the artists most closely identified with the Ashcan School.

His wariness was not misplaced: exhibitions of Ashcan art in recent decades often stress its documentary quality and importance as part of an historical record, whereas Sloan felt that any artist worth anything had to be appreciated for his skilled brushwork, color, and composition.

"Sloan's approach to making urban realist art was based on images seen and remembered (and sometimes written down) rather than sketched in the street, even though his autographic handling of paint and print media conveys the look of a rapid drawing.

A student of his wrote, he "concerned himself with what we call genre: street scenes, restaurant life, paintings of saloons, ferry boats, roof tops, back yards, and so on through a whole catalogue of commonplace subjects.

"[34] In the late 1920s, just as the market for his city pictures was finally reaching a point at which he might have made a comfortable living, Sloan changed his technique and abandoned his characteristic urban subject matter in favor of nudes and portraits.

Rejecting as superficial the spontaneous painterly technique of Manet and Hals—and also of Robert Henri and George Luks—he turned instead to the underpainting and glazing method used by old masters such as Andrea Mantegna.

His students included Peggy Bacon, Aaron Bohrod, Alexander Calder, Reginald Marsh, Xavier J. Barile, Barnett Newman, Minna Citron, and Norman Raeben.

In American Visions, the critic Robert Hughes praised Sloan's art for "an honest humaneness, a frank sympathy, a refusal to flatten its figures into stereotypes of class misery ...

"[36] In American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression, art historian Milton Brown called Sloan "the outstanding figure of the Ash Can School.