John W. Campbell

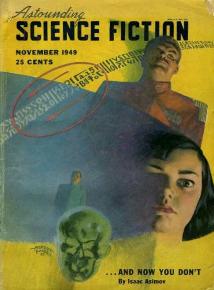

In his capacity as an editor, Campbell published some of the very earliest work, and helped shape the careers of virtually every important science-fiction author to debut between 1938 and 1946, including Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and Arthur C. Clarke.

[3] Campbell attended the Blair Academy, a boarding school in rural Warren County, New Jersey, but did not graduate because of lack of credits for French and trigonometry.

[4] He also attended, without graduating, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was befriended by the mathematician Norbert Wiener (who coined the term cybernetics) – but he failed German.

Who Goes There?, about a group of Antarctic researchers who discover a crashed alien vessel, formerly inhabited by a malevolent shape-changing occupant, was published in Astounding almost a year after Campbell became its editor and it was his last significant piece of fiction, at age 28.

[25] At the time of his sudden death after 34 years at the helm of Analog, Campbell's personality and editorial demands had alienated some of his writers to the point that they no longer submitted works to him.

Campbell convinced them that by removing the magazine "the FBI would be advertising to everyone that such a project existed and was aimed at developing nuclear weapons" and the demand was dropped.

Writer Joe Green recounted that Campbell had rejected Godwin's 'Cold Equations' on three different occasions due to disagreements over the fate of the female protagonist.

[35] Green wrote that Campbell "enjoyed taking the 'devil's advocate' position in almost any area, willing to defend even viewpoints with which he disagreed if that led to a livelier debate".

As an example, he wrote: [Campbell] pointed out that the much-maligned 'peculiar institution' of slavery in the American South had in fact provided the blacks brought there with a higher standard of living than they had in Africa ...

I suspected, from comments by Asimov, among others – and some Analog editorials I had read – that John held some racist views, at least in regard to blacks.Finally, however, Green agreed with Campbell that "rapidly increasing mechanization after 1850 would have soon rendered slavery obsolete anyhow.

I sat on a panel with him in 1965, as he pointed out that the worker bee when unable to work dies of misery, that the moujiks when freed went to their masters and begged to be enslaved again, that the ideals of the anti-slavers who fought in the Civil War were merely expressions of self-interest and that the blacks were 'against' emancipation, which was fundamentally why they were indulging in 'leaderless' riots in the suburbs of Los Angeles.

[38]By the 1960s, Campbell began to publish controversial essays supporting segregation and other remarks and writings surrounding slavery and race, which distance him from many in the science fiction community.

[41] On February 10, 1967, Campbell rejected Samuel R. Delany's Nova a month before it was ultimately published, with a note and phone call to his agent explaining that he did not feel his readership "would be able to relate to a black main character".

For example, Campbell accepted Isaac Asimov's proposal for what would become "Homo Sol" (where humans rejected an invitation to join a galactic federation) in January 1940, which was published later that year in the September edition of Astounding Science Fiction.

[43] Similarly, Arthur C. Clarke's "Rescue Party" and Fredric Brown's "Arena" (basis of the Star Trek episode of the same name) and "Letter to a Phoenix" (all first appeared in Astounding) also depict humans favorably above aliens.

In the Analog of September 1964, nine months after the Surgeon General's first major warning about the dangers of cigarette smoking had been issued (January 11, 1964) Campbell ran an editorial, "A Counterblaste to Tobacco" that took its title from the anti-smoking book of the same name by King James I of England.

[46] In a one-page piece about automobile safety in Analog dated May 1967, Campbell wrote of "people suddenly becoming conscious of the fact that cars kill more people than cigarettes do, even if the antitobacco alarmists were completely right..."[47] In 1963, Campbell published an angry editorial about Frances Oldham Kelsey who, while at the FDA, refused to permit thalidomide to be sold in the United States.

[50][51] In the 1930s, Campbell became interested in Joseph Rhine's theories about ESP (Rhine had already founded the Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University when Campbell was a student there),[52] and over the following years his growing interest in parapsychology would be reflected in the stories he published when he encouraged the writers to include these topics in their tales,[53] leading to the publication of numerous works about telepathy and other "psionic" abilities.

This post-war "psi-boom"[54] has been dated by science fiction scholars to roughly the mid-1950s to the early 1960s, and continues to influence many popular culture tropes and motifs.

Campbell rejected the Shaver Mystery in which the author claimed to have had a personal experience with a sinister ancient civilization that harbored fantastic technology in caverns under the earth.

When Hubbard's therapy failed to find support from the medical community, Campbell published the earliest forms of Dianetics in Astounding.

He pained very many of the men he had trained (including me) in doing so, but felt it was his duty to stir up the minds of his readers and force curiosity right out to the border lines.

He began a series of editorials ... in which he championed a social point of view that could sometimes be described as far right (he expressed sympathy for George Wallace in the 1968 national election, for instance).

[61] "He was a tall, large man with light hair, a beaky nose, a wide face with thin lips, and with a cigarette in a holder forever clamped between his teeth", wrote Asimov.

"[64] British novelist and critic Kingsley Amis dismissed Campbell brusquely: "I might just add as a sociological note that the editor of Astounding, himself a deviant figure of marked ferocity, seems to think he has invented a psi machine.

[66] British science-fiction novelist Michael Moorcock, as part of his "Starship Stormtroopers" editorial, said Campbell's Astounding and its writers were "wild-eyed paternalists to a man, fierce anti-socialists" with "[stories] full of crew-cut wisecracking, cigar-chewing, competent guys (like Campbell's image of himself)"; they sold magazines because their "work reflected the deep-seated conservatism of the majority of their readers, who saw a Bolshevik menace in every union meeting".

[38] SF writer Alfred Bester, an editor of Holiday Magazine and a sophisticated Manhattanite, recounted at some length his "one demented meeting" with Campbell, a man he imagined from afar to be "a combination of Bertrand Russell and Ernest Rutherford".

The first thing Campbell said to him was that Freud was dead, destroyed by the new discovery of Dianetics, which, he predicted, would win L. Ron Hubbard the Nobel Peace Prize.

He dedicated The Early Asimov (1972) to him, and concluded it by stating that "There is no way at all to express how much he meant to me and how much he did for me except, perhaps, to write this book evoking, once more, those days of a quarter century ago".

[72] Campbell and Astounding shared one of the inaugural Hugo Awards with H. L. Gold and Galaxy at the 1953 World Science Fiction Convention.