Storer College

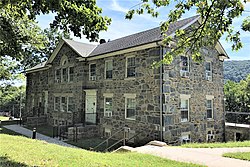

Situated at an almost clifftop location, the college site overlooks the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers[,] over which tower the majestic Blue Ridge Mountains.

Its first class was 19 formerly enslaved children, described as "poorly clad, ill-kept, and undisciplined", who desperately needed the basic skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

[5]: 263 At a conference in 2015 honoring the 150th anniversary of Storer College, John Cuthbert, head of the West Virginia & Regional History Center, observed: It is almost impossible for us to comprehend today how revolutionary the establishment of an African-American school was at the close of the Civil War.

[7]: 466 A $10,000 matching grant from John Storer,[8] a philanthropist from Maine, led to the charter of "a school which might eventually become a College, to be in located in one of the Southern States, at which youth could be educated without distinction of race or color".

In 1865, as a representative of New England's Freewill Baptist Home Mission Society, charged with coordinating their instructional efforts in the Shenandoah Valley and surrounding areas, Reverend Nathan Cook Brackett chose centrally-located Harpers Ferry as his base.

The Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, on low ground adjoining the rail line and the Potomac, was destroyed during the Civil War and was never rebuilt, and the lower town was in poor condition.

From Harpers Ferry, Reverend Brackett directed the efforts of dedicated missionary teachers, who provided a basic education to thousands of former slaves congregated in the relatively safe haven of the Shenandoah Valley by the end of the American Civil War.

[14]: 5 The money was raised, and by March 1868 Storer received its state charter, which was approved in the Legislature by a vote of 13–6,[15]: 181 though the phrase "without distinction of race or color" was fiercely debated.

No one saw this as a problem; it was what the West Virginia Legislature expected when they chartered Storer College, described as "a high school for negroes" by a hostile newspaper.

In addition, Storer was to receive $1,785 from the sale of Manning Bible School (Cairo, Illinois) property,[24]: 125 In 1926, the Legislature appropriated $6,000, which did not even cover half the faculty and administrative salaries.

The Freewill Baptists' other mission school, resembling that in Harpers Ferry, in Beaufort, North Carolina, was abandoned after one year due to "lingering Confederate sympathizers".

The school had at one point a Modern Minstrel Company, which performed "Plantation Songs and Melodies” and renditions of numbers like “If the Man in the Moon Was a Coon".

One has only to linger there a short time, go through a week of commencement, to realize that that institution is doing a glorious, a far-reaching work, impossible of estimate for the colored race.

[26]: 19 They passed a resolution condemning "the authorities of Storer College for preventng those who have contributed for thesupport of Lincoln Hall from using the latter during the present summer, as has been the custom heretofore.

Du Bois, a sociologist with a PhD, rejected the prevalent theory of "accommodation", as opposed to social equality, promoted by Booker T. Washington, President of the Tuskegee Institute.

The program for its first meeting, celebrated in Fort Erie, Ontario, for fear of disruptions in Buffalo, New York, was typed on the back of Storer letterhead.

The Niagara Movement published an annual "Address to the World", demanding voting rights (the mass of African Americans in the South had been essentially disenfranchised by the turn of the century), educational and economic opportunities, justice in the courts, and recognition in unions and the military.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in New York City in 1910 with an interracial board, and many of the members of the failing Niagara Movement quickly joined it.

The NAACP had many of the same goals of the Niagara Movement; it also pursued a concentrated program of litigation campaigns in the effort to overturn of barriers to voter registration and voting, end state and local jurisdictions' segregation of housing, gain integrated public transportation and other facilities, seek integrated public education, achieve fair jury trials for blacks, and similar goals.

It is commonly said that Storer closed because state funding ended after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling found segregated public schools to be unconstitutional.

In 1954, the NAACP achieved a victory with the US Supreme Court decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case, which declared racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional.

According to the first college catalog, students were to "receive counsel and sympathy, learn what constitutes correct living, and become qualified for the performance of the great work of life."

[1] In 1911, the West Virginia Legislature struck Storer from its list of accredited normal programs, meaning its graduates could not receive teaching certificates, because "the curriculum did not adequately include enough professional training.

[10]: xxvii This formalization of manual labor at Storer corresponded with a widespread movement in the South that was predicated upon white supremacists['] notions of black inferiority.

[42]: 4 Hamilton Hatter, an African American from Jefferson County, first studied at Storer, then received a bachelor's degree from Bates College in 1888 (where he ran a sawmill).

[44]: 103 At that time there were 7 full-time and 4 part-time teachers, no courses beyond the high school level, an outdated library, inadequate science labs and equipment, and buildings in desperate need of essential repairs.

Tensions became worse because McKinney worked to strengthen the College's ties to Africa, including inviting alumnus Nnamdi Azikiwe, President of Nigeria, as commencement speaker in 1947.

In 1872 Storer started its first academic, four-year department, the Seminary Course [high school]; it taught classics, including Latin, Greek, and Shakespeare, along with astronomy, algebra, geometry, and botany.

[5]: 265 According to Storer's first catalogue (1869), students were to "receive counsel and sympathy, learn what constitutes correct living, and become qualified for the great work of life".

[63] The National Park Service library and archive in Harpers Ferry has many items, and the Jefferson County Museum, in Charles Town, has a permanent exhibit, "The Founding of Storer College".