John of Brienne

John was the first king of Jerusalem to visit Europe (Italy, France, England, León, Castile and Germany) to seek assistance for the Holy Land.

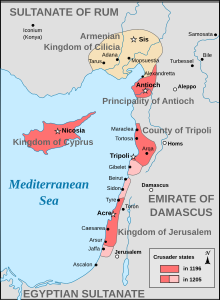

John III Vatatzes, Emperor of Nicaea, and Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria occupied the last Latin territories in Thrace and Asia Minor, besieging Constantinople in early 1235.

[11] A church career was not unusual for youngest sons of 12th-century noblemen in France; however, if his father sent John to a monastery he left before reaching the age of taking monastic vows.

[20] According to one version, the leading lords of Jerusalem sent envoys to France in 1208 asking Philip II to select a French nobleman as a husband for their queen, Maria.

[31] Pope Innocent confirmed John as lawful ruler of the Holy Land in early 1213, urging the prelates to support him with ecclesiastical sanctions if needed.

[32] Most of the Jerusalemite lords remained loyal to the king, acknowledging his right to administer the kingdom on behalf of his infant daughter;[33] John of Ibelin left the Holy Land and settled in Cyprus.

[38] Quarrels among John, Leo I, Hugh I and Bohemond IV are documented by Pope Innocent's letters urging them to reconcile their differences before the Fifth Crusade reached the Holy Land.

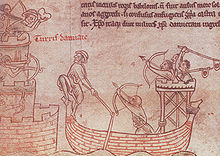

[56] Although they seized a strategically important tower on a nearby island on 24 August,[54][53] Al-Kamil (who had succeeded Al-Adil I in Egypt) controlled traffic on the Nile.

[61] Although John and the secular lords were willing to accept the sultan's offer, Pelagius and the heads of the military orders resisted; they said that the Moslems could easily recapture the three towns.

[73] Contemporary sources accused John of causing her sudden death, claiming that he severely beat her when he heard that she tried to poison his daughter Isabella.

[73] Soon after Pope Honorius learned about the deaths of Stephanie and her son, he declared Raymond-Roupen the lawful ruler of Cilicia and threatened John with excommunication if he fought for his late wife's inheritance.

[75] According to a letter from the prelates in the Holy Land to Philip II of France, lack of funds kept John from leaving his kingdom.

[88] To plan the military campaign, the pope and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II met at Ferentino in March 1223;[89] John attended the meeting.

[90] He agreed to give his daughter in marriage to Frederick II after the emperor promised that he would allow John to rule the Kingdom of Jerusalem for the rest of his life.

[91] Matilda I, Countess of Nevers, Erard II of Chacenay, Albert, Abbot of Vauluisant and other local potentates asked John to intervene in their conflicts, indicating that he was esteemed in his homeland.

[99][100] Balian of Sidon, Simon of Maugastel, Archbishop of Tyre, and the other Jerusalemite lords who had escorted Isabella to Italy acknowledged Frederick as their lawful king.

[102] In an attempt to take advantage of the revived Lombard League (an alliance of northern Italian towns) against Frederick II, John went to Bologna.

[104] The dying Pope Honorius appointed John rector of a Patrimony of Saint Peter in Tuscany (part of the Papal States) on 27 January 1227,[105][106] and urged Frederick II to restore him to the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

[103] Honorius' successor, Gregory IX, confirmed John's position in the Papal States on 5 April[107] and ordered the citizens of Perugia to elect him their podestà.

[107] Gregory excommunicated Frederick II on 29 September 1227, accusing him of breaking his oath to lead a crusade to the Holy Land;[108] the emperor had dispatched two fleets to Syria, but a plague forced them to return.

[111] Although John defeated the invaders in a series of battles, it took a counter-invasion by another papal army in southern Italy to drive Rainald back to Sulmona.

[112] John laid a siege before returning to Perugia in early 1229 to conclude negotiations with envoys of the Latin Empire of Constantinople, who were offering him the imperial crown.

[114] After months of negotiation, John and the envoys from the Latin Empire signed a treaty in Perugia which Pope Gregory confirmed on 9 April 1229.

[117] Frederick II (who had crowned himself king of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre) returned to Italy, forcing the papal troops to withdraw.

[123] Shortly after John left for Constantinople in August, Pope Gregory acknowledged Frederick II's claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

[126] The Venetians urged him to wage war against John III Vatatzes, Emperor of Nicaea, who supported a rebellion against their rule in Crete.

[127] According to Philippe Mouskes' Rhymed Chronicle, John could make "neither war nor peace";[125] because he did not invade the Empire of Nicaea, most French knights who accompanied him to Constantinople returned home after his coronation.

[125] To strengthen the Latin Empire's financial position, Geoffrey II of Achaea (John's most powerful vassal) gave him an annual subsidy of 30,000 hyperpyra after his coronation.

[138] They agree that John's declining health contributed to his conversion, but Bernard also described a recurring vision of an old man urging the emperor to join the Franciscans.

[141] In a third theory, proposed by Giuseppe Gerola, a tomb decorated with the Latin Empire coat of arms in Assisi's Lower Basilica may have been built for John by Walter VI, Count of Brienne.