Nuova Cronica

[2] In his Cronica, Villani described in detail the many building projects of the city, statistical information on population, ordinances, commerce and trade, education, and religious facilities.

Giovanni Villani's Cronica is divided into twelve books; the first six deal with the largely legendary history of Florence, starting at conventionally Biblical times to 1264.

[14] In this civil war, the Guelphs were a faction united with the papacy in Rome, while the Ghibellines were allied with the descendants of Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire and supported by Siena.

Villani relates that for the construction of the church, it was required of the Commune of Florence that a subsidy of four denari on each libra be paid out of the city treasury in addition to a head-tax of two soldi for each adult male.

[15] On July 18, 1334, work began on the new campanile (bell tower) of the cathedral, the first stone placed by the bishop of Florence in front of an audience of clergy, priors, and other magistrates.

[15] According to Villani, in 1299, the commune and people of Florence laid the foundation for the Palazzo Vecchio, to replace the town hall that was located in a house behind the church of San Brocolo.

[16] In planning for the large expanse of the plaza, the commune of Florence purchased the homes of citizens such as the Foraboschi family, so that they could be demolished to make room for construction.

[17] However, Villani is quick to add that those who spent too much on the lavish excesses of continuous remodelling and refurnishing of homes were sinners and could be "considered crazy because of their extravagant spending".

[18] Villani also describes the growing trend in the early 14th century of affluent Florentine citizens building large country homes far outside the walls of Florence, in the hills of Tuscany.

[20] There was a famine in 1328 which not only devastated Florence, but caused the people of Perugia, Siena, Lucca, and Pistoia to turn away any beggars who approached their towns because they could not provide them with food.

[22] Villani writes of the bread riots of the poor who could not afford a whole staio of wheat with their meager salaries: ...as long as the scarcity lasted, disregarding the heavy charge upon the public purse, it kept the price of the staio at half a gold florin [which would be two and a half times the normal figure] although to affect this reduction it permitted the wheat to be mixed to one-fourth its volume with coarser grain.

In spite of all the government did, the agitation of the people at the market of Or San Michele was so great that it was necessary to protect the officials by means of guards fitted out with ax and block to punish rioters on the spot with the loss of hands or feet.

[22] In order to save their own funds and calm the rage of the riotous poor, all the baker's ovens in the city were requisitioned by the commune and a loaf of bread weighing 170 g (6 oz) was then sold at a meager four pennies.

[24] On September 12 of that same year a fire broke out at the household of the Soldanieri, killing six people in a house of carpenters and a blacksmith that was located near the church of Santa Trinità.

[22] Bartlett notes that these columns, presented to Florence by the Pisans more than two hundred years before, have scratched lines to this day indicating the water level reached by the flood in 1333.

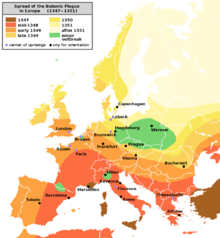

[26] Villani describes how the plague of Black Death in 1348 was much more widespread amongst the inhabitants of Pistoia, Prato, Bologna, Romagna, Avignon and the whole of France than it was in Florence and Tuscany.

[24] He notes that the Black Death also killed many more in Greece, Turkey (Anatolia), in countries amongst the Tartars and in places "beyond the sea", across the whole Levant and Mesopotamia in the areas of Syria and "Chaldea", as well as the islands of Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Elba, and "from there soon reached all the shores of the mainland".

The total number of churches in Florence and its suburbs was 110—including 57 parishes, five abbeys with two priors and 80 monks each, 24 nunneries with some 500 women, 10 orders of friars, and 30 hospitals with over 1,000 beds to offer to the sick and dying.

[27] Giovanni notes that earlier in Florence there were actually 300 workshops producing 100,000 pieces of cloth annually, but these were of coarser quality and lesser value (before the importation and knowledge of English wool).

"[28][29] In 1293, new city ordinances were passed that stated anyone who did not belong to a guild or a council of the captain of the people were to be barred from serving as priors, standard-bearers of justice, or judges.

Earlier chronicles, such as the Chronica de origine civitatis of 1231, provided little substantive or factual material, relying instead on legendary accounts and not venturing to analyze their historicity or question their validity.

[10] Kenneth R. Bartlett writes that Villani's interest and elaboration in economic details, statistical information, and political and psychological insight signifies him as a more modern late medieval chronicler of Europe.