John of Bohemia

[4] The wedding took place in Speyer, after which the newlyweds made their way to Prague accompanied by a group led by the experienced diplomat and expert on Czech issues, Peter of Aspelt, Archbishop of Mainz.

Because the emperor had imperial Czech regiments accompany and protect the couple from Nuremberg to Prague, John was thus forced to invade Bohemia on behalf of his wife Elizabeth.

[5] The castle at Prague was uninhabitable, so John made residence in one of the houses on the Old Town Square, and with the help of his advisors, he stabilized affairs in the Czech state.

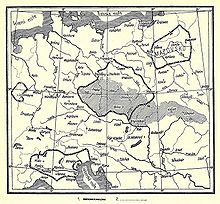

He thereby became one of the seven prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire and – in succession of his brother-in-law Wenceslaus III of Bohemia – claimant to the Polish and Hungarian throne.

Nevertheless, John later would support Louis IV in his rivalry with Frederick the Fair, King of Germany, culminating in the 1322 Battle of Mühldorf in which, in return, he received the Czech region of Egerland as a reward.

He parted ways with his wife and left the Czech country to be ruled by the barons while spending time in Luxembourg and the French court.

In 1335 in Congress of Visegrád, Władysław's successor King Casimir III the Great of Poland paid a significant amount of money in exchange for John's giving up his claim to the Polish throne.

The growing tensions within the aristocracy and the lack of communication due to John's consistent absence in Bohemia led to a competition between two factions of the Czech nobility.

The other party, led by Vilém Zajíc of Valdek (Latin: Wilhelmus Lepus de Waldek;[8] German: Wilhelm Hase von Waldeck), convinced the Queen that Lord Lipá intended to overthrow John.

By 1318, John had reconciled with the nobility and recognised their rights, further establishing dualism of the Estates and a government division between the king and the nobles.

At the Battle of Crécy in 1346 John controlled Phillip's advanced guard along with managing the large contingents of Charles II of Alençon and Louis I, Count of Flanders.

The medieval chronicler Jean Froissart left the following account of John's last actions: ...for all that he was nigh blind, when he understood the order of the battle, he said to them about him: 'Where is the lord Charles my son?'

The lord Charles of Bohemia his son, who wrote himself king of Almaine and bare the arms, he came in good order to the battle; but when he saw that the matter went awry on their party, he departed, I cannot tell you which way.

The king his father was so far forward that he strake a stroke with his sword, yea and more than four, and fought valiantly and so did his company; and they adventured themselves so forward, that they were there all slain, and the next day they were found in the place about the king, and all their horses tied each to other.According to the Cronica ecclesiae Pragensis Benesii Krabice de Weitmile,[12] when told by his aides that the battle against the English at Crécy was lost and he better should flee to save his own life, John the Blind replied: "Absit, ut rex Boemie fugeret, sed illuc me ducite, ubi maior strepitus certaminis vigeret, Dominus sit nobiscum, nil timeamus, tantum filium meum diligenter custodite.

His son Jean-François Boch met with the future King Frederick William IV of Prussia on his voyage through the Rhineland in 1833, offering the remains as a gift.

As Frederick William counted John the Blind among his ancestors, he ordered Karl Friedrich Schinkel to construct a funeral chapel.