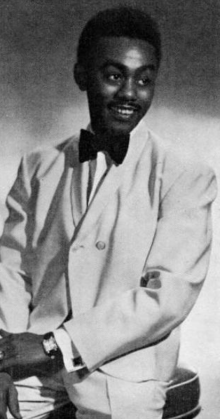

Johnnie Taylor

As an adult, he had one release, "Somewhere to Lay My Head", on Chicago's Vee Jay Records label in the 1950s, as part of the gospel group The Highway Q.C.

[8] Taylor, along with Isaac Hayes and The Staple Singers, was one of the label's flagship artists, who were credited for keeping the company afloat in the late 1960s and early 1970s after the death of its biggest star, Otis Redding, in an aviation accident.

[5] Taylor recorded several more successful albums and R&B single hits with Davis on Columbia, before Brad Shapiro took over production duties, but sales generally fell away.

After a short stay at a small independent label in Los Angeles, Beverly Glen Records, Taylor signed with Malaco Records[5] after the company's founder Tommy Couch and producing partner Wolf Stephenson heard him sing at blues singer Z.

Backed by members of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, as well as in-house veterans such as former Stax keyboardist Carson Whitsett and guitarist/bandleader Bernard Jenkins, Malaco gave Taylor the type of recording freedom that Stax had given him in the late 1960s and early 1970s, enabling him to record ten albums for the label in his 16-year stint.

With this success, Malaco recorded a live video of Taylor at the Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas, Texas, in the summer of 1997.

Taylor's final song was "Soul Heaven", in which he dreamed of being at a concert featuring deceased African-American music icons from Louis Armstrong to Otis Redding to Z.Z.

Taylor died of a heart attack at Charlton Methodist Hospital in Dallas, Texas, on May 31, 2000, aged 66.

He was buried beside his mother, Ida Mae Taylor, at Forrest Hill Cemetery in Kansas City, Missouri.

Having six accepted children and three others with confirmed paternity born to three different mothers,[13] the difficulties associated with executing his will were presented in an episode of the TV program The Will: Family Secrets Revealed called "The Estate of Johnnie Taylor".

[14] In a 2021 Rolling Stone article, Fonda Bryant, one of the nine heirs of Taylor's estate, shared some of the complexities that she and her other siblings have had to deal with during the past decade regarding her father's royalty payments from Sony Music.

Bryant believed that the alleged lack of transparency concerning those payouts was reason enough for Sony to disclose her father's personal information.

Music industry attorney Erin M. Jacobson stated in the article that "'a label is not just going to turn over a bunch of financial records to anyone that asks for it.'"