Johns Hopkins

Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for most of his life.

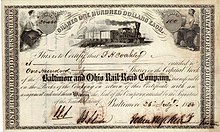

Hopkins invested heavily in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), which eventually led to his appointment as finance director of the company.

His concern for the poor and newly freed slave populations drove him to create free medical facilities, orphanages, asylums, and schools to help alleviate the impoverished conditions for all, regardless of race, sex, age, or religion, but especially focused on the young.

Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795, at his family's home of White's Hall, a 500-acre (200 ha) tobacco plantation in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

[2][3][4][5] He was one of eleven children born to Samuel Hopkins of Crofton, Maryland, and Hannah Janney, of Loudoun County, Virginia.

[7] The second eldest of eleven children, Hopkins was required to work on the farm alongside his siblings and indentured and free Black laborers.

[9] The company prospered by selling various wares in the Shenandoah Valley from Conestoga wagons, sometimes in exchange for corn whiskey, which was then sold in Baltimore as "Hopkins' Best".

The bulk of Hopkins's fortune, however, was made by his judicious investments in myriad ventures, most notably the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), of which he became a director in 1847 and chairman of the Finance Committee in 1855.

[12][13] One of the first campaigns of the American Civil War was planned at Hopkins' summer estate, Clifton, where he had also entertained a number of foreign dignitaries, including the future King Edward VII.

Hopkins' support of Abraham Lincoln also often put him at odds with some of Maryland's most prominent people, including Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney who continually opposed Lincoln's presidential decisions such as limiting habeas corpus and stationing Union Army troops in Maryland.

In 1862, Hopkins wrote a letter to Lincoln requesting that he not heed the detractors' calls and continue to keep soldiers stationed in Maryland.

In an email sent from Johns Hopkins University to all employees on December 9, 2020, the university wrote that, "The current research done by Martha S. Jones and Allison Seyler finds no evidence to substantiate the description of Johns Hopkins as an abolitionist, and they have explored and brought to light a number of other relevant materials.

In a pre-print paper published by the Open Science Framework, these scholars argue that Johns Hopkins's parents and grandparents were devout Quakers who liberated the family's enslaved laborers prior to 1800, that Johns Hopkins was an emancipationist who supported the movement to end slavery within the limits of the laws governing Maryland, and that the available documentation, including relevant tax records these researchers have uncovered, does not support the university's claim that Johns Hopkins was a slaveholder.

[10][21][22] Prior to the Civil War, Johns Hopkins worked closely with two of America's most famous abolitionists, Myrtilla Miner[23] and Henry Ward Beecher.

Before the war, there was significant written opposition to his support for Myrtilla Miner's founding of a school for African American females (now the University of the District of Columbia).

[28] In a letter to the editor, one subscriber to the widely circulated De Bow's Review wrote: "It now seems that the Abolitionists not only propose to colonize Virginia from their own numbers, but that they are about to make the District of Columbia, in the midst of the slave region, and once under the jurisdiction of a slave State, the centre of an education movement, which shall embrace the free negroes of the whole North.

Hopkins lived his entire adult life in Baltimore and made many friends among the city's social elite, many of them Quakers.

[32] In these documents, Hopkins made provisions for scholarships to be provided for poor youths in the states where he had made his wealth and assistance to orphanages other than the one established for African American children, to members of his family, to those he employed, his cousin Elizabeth, to other institutions for the care and education of youths regardless of color, and the care of the elderly and the ill, including the mentally ill and convalescents.

This provision will secure the services of women competent to care for those sick in the hospital wards, and will enable you to benefit the whole community by supplying it with a class of trained and experienced nurses".

[1] In 1973, Johns Hopkins was cited prominently in the Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Americans: The Democratic Experience by Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress from 1975 to 1987.

In 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a $1 postage stamp in Hopkins' honor, as part of the Great Americans series.