Ardagh–Johnson Line

[8] Accordingly, he engaged in a hasty north–south traverse survey of the hitherto-unexplored Aksai Chin, following the main trade route — averaging about thirty miles per day.

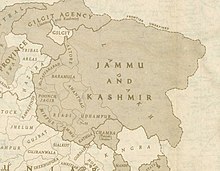

The boundary of Kashmir that he drew, stretching from Sanju Pass to the eastern edge of Chang Chenmo Valley along the Kunlun mountains, is referred to as the "Johnson Line".

[12] Since the late 1800s, local government officials were increasingly unhappy with accuracy of such traverse-maps and as a result, new surveys (along with boundary commissions) were frequently set up.

However, extremely inhospitable geological conditions of Northeast Kashmir and difficulty in determining water-sheds across the Aksai Chin meant a continued lack of precision surveys covering this region.

In 1888, the Joint Commissioner of Ladakh requested India's Foreign Department to demarcate boundaries across northern and eastern Kashmir in a clear manner.

After much back and forth, the department concluded that Johnson (and those who followed him) had an unconvincing view of the Indus watershed and their traverse-maps were too imprecise (and lacking in details) to serve the purpose of adjudicating territorial boundaries.

In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River.