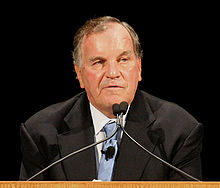

Jon Burge

He was found guilty of lying about "directly participating in or implicitly approving the torture" of at least 118 people in police custody in order to force false confessions.

[2][3] In 2008, Patrick Fitzgerald, United States Attorney for Northern Illinois, charged Burge with obstruction of justice and perjury in relation to testimony in a 2003 civil suit against him for damages for alleged torture.

Of Norwegian descent, Floyd was a blue collar worker for a phone company while Ethel was a consultant and fashion writer for the Chicago Daily News.

[4] During his military service, Burge earned a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry and two Army Commendation Medals for valor, for pulling wounded men to safety while under fire.

Initial interrogation procedures allegedly included shooting pets of suspects, handcuffing subjects to stationary objects for entire days, and holding guns to the heads of minors.

[11] By the end of the day, he was taken by police and admitted to Mercy Hospital and Medical Center with lacerations on various parts of his head, including his face, chest bruises and second-degree thigh burns.

[22] A medical officer who saw Andrew Wilson sent a memo to Richard M. Daley, then Cook County State's Attorney, asking for his case to be investigated on suspicion of police brutality.

[27] After five days of deliberation, the jury was unable to agree on Wilson's eligibility for the death penalty; ten women were in favor of imposing this sentence and two men opposed it.

[42][43] Danny K. Davis, who was running for Chicago mayor in the Democratic primary scheduled for February 26, 1991, made police brutality and excessive force an issue in the campaign.

[55] The Chicago Police Board set a November 25 hearing to formalize the firing of Burge and two detectives based on 30 counts of abuse and brutality against Wilson.

[57] After having spent $750,000 to defend Burge in the Wilson case, the City of Chicago debated whether to follow normal procedures and pay for the defense of its police officers.

[79][80][81] In 1999, lawyers for several death row inmates began to call for a special review of convictions that were based on evidence and confessions extracted by Burge and his colleagues.

[84] Several politicians, including US Representative Bobby Rush, requested that State's Attorney Richard A. Devine seek new trials for the Death Row 10 who were allegedly tortured by Burge into making coerced confessions.

[97] Given the number of cases of alleged brutality to be investigated, inmates who claimed to have been abused and gave coerced confessions were offered reduced sentences in exchange for dropping charges.

[101][102] In addition, Ryan had already pardoned four death row inmates: Madison Hobley, Aaron Patterson, Leroy Orange and Stanley Howard, who were among the ten who claimed they were coerced into confessing by Burge and his officers and had been wrongfully convicted.

[103][104] Daley, at the time the Cook County State's Attorney, has been accused by the Illinois General Assembly of failing to act on information he possessed on the conduct of Burge and others.

[120] A special prosecutor was hired because Cook County State's Attorney, Richard Devine, had a conflict of interest stemming from his tenure at the law firm of Phelan, Pope & John, which had defended Burge in two federal suits.

[125] On September 1, 2004, Burge was served with a subpoena to testify before a grand jury in an ongoing criminal investigation of police torture while in town for depositions on civil lawsuits at his attorney's office.

[127] The incident prompted the city to request the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to allot the torture victims an hour-long hearing at their October 2005 session.

[96] The investigation revealed that in three of the cases, prosecutors could have proved, beyond a reasonable doubt in court, that torture by the police had occurred; five former officers including Burge were involved.

The Committee notes the limited investigation and lack of prosecution in respect of the allegations of torture perpetrated in areas 2 and 3 of the Chicago Police Department (art.

The State party should promptly, thoroughly and impartially investigate all allegations of acts of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment by law-enforcement personnel and bring perpetrators to justice, in order to fulfil its obligations under article 12 of the Convention.

The reforms are among the 80 recommendations made by the Illinois Commission on Capital Punishment, formed in 2000 by former Governor George Ryan to address wrongful convictions and the state's broken death penalty system.

[148] The charges were the result of convicted felon Madison Hobley's 2003 civil rights lawsuit alleging police beatings, electric shocks and death threats by Burge and other officers against dozens of criminal suspects.

[151][152] Also in April, Cortez Brown, an inmate who had sought a new trial with respect to his conviction in two 1990 murders, to which he said he had confessed under physical coercion, had already subpoenaed two Chicago police detectives for his May 18, 2009, hearing.

[169] In April 2014, the Better Government Association, a non-partisan watchdog group, reported that the city of Chicago had spent more than $521.3 million in the previous decade on lawsuit settlements, judgments, and legal fees for defenses related to police misconduct.

More than a quarter, or $110.3 million, was related to 24 wrongful-conviction lawsuits, a dozen of which involved Burge, whose detectives were accused of torturing confessions out of mostly black male suspects over many years.

[173] Discussing the larger culture of violence that Chicago police had created, journalist Spencer Ackerman in February 2015 reported that Zuley, by then retired from CPD, had served in 2003–2004 with the US Navy Reserve as an interrogator at Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, established by the George W. Bush administration.

[180] At the May Council meeting, as more than a dozen Burge survivors looked on, Mayor Emanuel offered an official apology on behalf of the City of Chicago, and the aldermen stood and applauded.

[182] G. Flint Taylor, an attorney with the People's Law Office and part of the legal team that negotiated the deal, said in an interview that the "non-financial reparations make it truly historic".