Joseph E. Johnston

Johnston was trained as a civil engineer at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, graduating in the same class as Robert E. Lee.

Johnston defended the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, withdrawing under the pressure of U.S. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's superior force.

In 1811, the Johnston family moved to Abingdon, Virginia, a town near the Tennessee border, where his father Peter built a home he named Panecillo.

He departed for Washington, D.C., in April 1838 and was appointed a first lieutenant of topographic engineers on July 7; on that same day, he received a brevet promotion to captain for the actions at Jupiter Inlet and his explorations of the Florida Everglades.

Despite this disagreement, Davis thought enough of Johnston to appoint him lieutenant colonel in one of the newly formed regiments, the 1st U.S. Cavalry at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, under Col. Edwin V. "Bull" Sumner, on March 1, 1855.

In addition, he suffered from the pressures of the imminent sectional crisis and the ethical dilemma of administering war matériel that might prove useful to his native South.

Having been educated in such opinions, I naturally determined to return to the State of which I was a native, join the people among whom I was born, and live with my kindred, and if necessary, fight in their defense.

[13] In the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), July 21, 1861, Johnston rapidly moved his small army from the Shenandoah Valley to reinforce that of Brig.

Johnston encountered a scattered unit, the 4th Alabama, whose field-grade officers had all been killed, and personally rallied the men to reinforce the Confederate line.

[14] It [the ranking of senior generals] seeks to tarnish my fair fame as a soldier and a man, earned by more than thirty years of laborious and perilous service.

I drew it in the war, not for rank or fame, but to defend the sacred soil, the homes and hearths, the women and children; aye, and the men of my mother Virginia, my native South.

But more importantly, it required him to replan his spring offensive, and instead of an amphibious landing at his preferred target of Urbanna, he chose the Virginia Peninsula, between the James and York Rivers, as his avenue of approach toward Richmond.

[18] In early April 1862, McClellan, having landed his troops at Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, began to move slowly toward Yorktown.

Lee began by driving McClellan from the Peninsula during the Seven Days Battles of late June and beating a U.S. army a second time near Bull Run in August.

Furthermore, in early April, Johnston was forced to bed with lingering problems from his Peninsula wound, and the attention of the Confederates shifted from Tennessee to Mississippi, leaving Bragg in place.

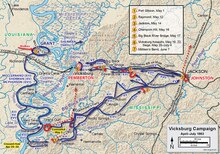

[24] Johnston began to move his force west to join Pemberton when he heard of that general's defeat at Champion Hill (May 16) and Big Black River Bridge (May 17).

Along with the capture of Port Hudson a week later, the loss of Vicksburg gave the United States complete control of the Mississippi River and cut the Confederacy in two.

[29] Faced with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's advance from Chattanooga to Atlanta in the spring of 1864, Johnston conducted a series of withdrawals that appeared similar to his Peninsula Campaign strategy.

He repeatedly prepared strong defensive positions, only to see Sherman maneuver around them in expert turning movements, causing him to fall back in the general direction of Atlanta.

A skirmish ensued, forcing the corps commander, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, to halt his advance and reposition his troops to face the threat.

Johnston had yielded over 110 miles of mountainous, and thus more easily defensible, territory in just two months, while the Confederate government became increasingly frustrated and alarmed.

In January 1865, the Congress passed a law authorizing Robert E. Lee the powers of general in chief, and recommending that Johnston be reinstated as the commander of the Army of Tennessee.

"[37] Vice President Alexander H. Stephens and 17 senators petitioned Lee to use his new authority to appoint Johnston, bypassing Davis, but the general in chief declined.

The Tennessee army had been severely depleted at Franklin and Nashville, lacked sufficient supplies and ammunition, and the men had not been paid for months; only about 6,600 traveled to South Carolina.

Johnston also had available 12,000 men under William J. Hardee, who had been unsuccessfully attempting to resist Sherman's advance, Braxton Bragg's force in Wilmington, North Carolina, and 6,000 cavalrymen under Wade Hampton.

On March 19, 1865, Johnston was able to catch the left wing of Sherman's army by surprise at the Battle of Bentonville and briefly gained some tactical successes before superior numbers forced him to retreat to Raleigh, North Carolina.

[40] After learning of Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, Johnston agreed to meet with General Sherman between the lines at a small farm known as Bennett Place near present-day Durham, North Carolina.

This was an act of generosity that Johnston would never forget; he wrote to Sherman that his attitude "reconciles me to what I have previously regarded as the misfortune of my life, that of having you to encounter in the field.

Grant supported his decisions in the Vicksburg Campaign: "Johnston evidently took in the situation, and wisely, I think, abstained from making an assault on us because it would simply have inflicted losses on both sides without accomplishing any result."

[49] In September 1890, a few months before he died, he was elected as an honorary member of the District of Columbia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution and was assigned national membership number 1963.