Joseph Grinnell

He made extensive studies of the fauna of California, and is credited with introducing a method of recording precise field observations known as the Grinnell System.

An unintended overnight stay on the island enabled him to study storm-petrels, an account of which he published in the March 1897 issue of the Nidologist,[5] an early publication of the Cooper Ornithological Club.

[6] Grinnell's expanding collection attracted visitors who were tourists, summer residents and visiting naturalists, including John Muir, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and ornithologist Joseph Mailliard.

[8] In Grinnell's letters, he described a chaotic scene as "the entire eight miles there is scarcely one hundred feet without one or more tents on it ... our claims are now covered with beach jumpers and we cannot get them off.

The Thayer expedition almost perished when their ship became locked in ice 7 nautical miles (13 km) off the coast, east of Point Barrow until the summer of 1914.

Satisfied of her commitment to research, he sent her a letter outlining specific points on field work that would maximize scientific results from the seven-member expedition.

Alexander and Grinnell believed the fauna and flora of the western territory was fast disappearing as a result of human impact, thus detailed documentation was essential for both posterity and knowledge.

This foresight proved useful almost a century later, when researchers at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology would use the Grinnell field notes to compare changes in California fauna.

[17] Alexander elaborated on the job requirements in a letter to Grinnell dated September, 1907 after she returned from Alaska: "I should like to see a collection developed (more especially of the California fauna) and would be glad to give what support I could if I could find the right man to take hold; someone interested not only in bringing a collection together but with the larger object in view, namely gathering data in connection with the work that would have direct bearing on the important biological issues of the day.

Alexander, in turn, expected Grinnell to devote all his time and energy to the enterprise, to continue research and publishing, in addition to the duties of director.

His reply elicited a sharp response from Alexander: "Am rather relieved you could not recommend a lady for our trip, though regret your evident contempt of women as naturalists ...

[23] The Condor published classified ads which listed items to buy, sell or trade for other specimens, collections, guns, cameras or publications.

[24] Grinnell also advertised to trade specimens in the magazine; the November 1906 issue contained the ad: "Wanted – will pay cash or good exchange in mammal or bird skins".

[24] In the same 1906 issue, Grinnell commented on Thomas Harrison Montgomery's article questioning the scientific benefit of egg collection (Oology) in Audubon Society's Bird-Lore publication.

We must confess that we have gotten more complete satisfaction, in other words happiness [italics in original], out of one vacation trip into the mountains after rare birds and eggs than out of our two years of University work in embryology!

[5] The 1914 Yosemite survey area consisted of 1,547 square miles (4,010 km2) in a narrow rectangle from eastern San Joaquin Valley, across the Sierra Nevada Range to the western edge of the Great Basin, including Mono Lake.

[32] There were 50 sites surveyed throughout the Lassen region of northern California which documented the distributions of more than 350 species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, and collected more than 4,500 specimens.

[33] The survey of California fauna was a test of Grinnell's theory that differences between species are driven by ecological and geographical barriers, a new idea in the science of biology of the 1940s.

The resurvey team encountered difficulties, as the 2007 report on Yosemite noted "the data from the original and current surveys cannot be directly compared because of differences in observer effort.

[36] Researchers have also observed selection-driven physical and genetic changes in populations of the Alpine chipmunk (Tamias alpinus), which was affected by contraction of its elevational range.

While most parts of the chipmunk genome had not changed, there were shifts in variants of a gene related to regulation of the animals’ ability to survive in low-oxygen environments (ALOX15).

In 60 surveys across 20 sites, they found the forest to be much denser than in Grinnell's time, with the loss of three species including a flying squirrel, and an increase in birds that like thick brush, such as the hermit thrush, the brown creeper and the Townsend's solitaire.

The relative lack of leaf litter and decayed ground cover in Grinnell's time was considered to make the occurrence of hot and lasting fires in the forest impossible.

[41] Grinnell and Tracy I. Storer's article "Animal Life as an Asset to National Parks" was published in Science on September 15, 1916, and presented two major points.

[42] The newly created National Park Service, in the Department of Interior, had no public education programs in 1916, although director designate Stephen Mather had read Grinnell's article in Science.

Despite this high-level expression of support, the idea of the park service being in the education business – beyond dispensing basic tourist information – was not widely accepted.

[42] Congress had passed legislation a year earlier that instructed the Bureau of Biological Survey (now the US Fish and Wildlife Service) to destroy predators that "are injurious to agriculture and animal husbandry on the national forests and the public domain ...".

Grinnell argued that, "As a rule, predaceous animals should be left unmolested and allowed to retain their primitive relation to the rest of the fauna ... as their number is already kept within proper limits by the available food supply, nothing is to be gained by reducing it still further."

"[49] The last confirmed California wolverine was killed seven years later by local trapper and miner Albert J. Gardisky in Mono County near Saddlebag Lake on February 22, 1922.

Preservationist Alexander McMillan Allen, the Save the Redwoods League environmental group and others began to buy back the residential lots in 1898.

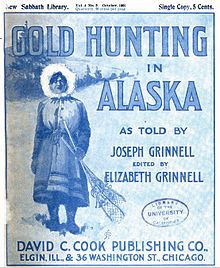

published in 1901