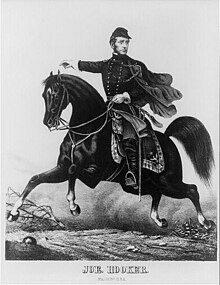

Joseph Hooker

At the start of the Civil War, he joined the Union side as a brigadier general, distinguishing himself at Williamsburg, Antietam and Fredericksburg, after which he was given command of the Army of the Potomac.

His ambitious plan for Chancellorsville was thwarted by Lee's bold move in dividing his army and routing a Union corps, as well as by mistakes on the part of Hooker's subordinate generals and his own loss of nerve.

Hooker returned to combat in November 1863, helping to relieve the besieged Union Army at Chattanooga, Tennessee, and continuing in the Western Theater under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, but departed in protest before the end of the Atlanta Campaign when he was passed over for promotion.

He received brevet promotions for his staff leadership and gallantry in three battles: Monterrey (to captain), National Bridge (major), and Chapultepec (lieutenant colonel).

His future Army reputation as a ladies' man began in Mexico, where local women referred to him as the "Handsome Captain".

[citation needed] The Handsome Captain struggled with the tedium of peacetime life and reportedly passed the time with liquor, ladies, and gambling.

[5] At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Hooker requested a commission, but his first application was rejected, possibly because of the lingering resentment harbored by Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the Army.

[citation needed] After he witnessed the Union Army defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, he wrote a letter to President Abraham Lincoln that complained of military mismanagement, promoted his own qualifications, and again requested a commission.

[6] In the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, Hooker commanded the 2nd Division of the III Corps and made a good name for himself as a combat leader who handled himself well and aggressively sought out the key points on battlefields.

The Peninsula cemented two further reputations of Hooker's: his devotion to the welfare and morale of his men, and his hard-drinking social life, even on the battlefield.

He asserted that the battle would have been a decisive Union victory if he had managed to stay on the field, but General McClellan's caution once again failed the Northern troops and Lee's much smaller army eluded destruction.

The War Department promptly acted on this recommendation, and Hooker received his brigadier's commission to rank from September 20.

His Grand Division (particularly V Corps) suffered serious losses in fourteen futile assaults ordered by Burnside over Hooker's protests.

Burnside followed up this battle with the humiliating Mud March in January and Hooker's criticism of his commander bordered on formal insubordination.

Burnside planned a wholesale purge of his subordinates, including Hooker, and drafted an order for the president's approval.

"[7] Lincoln wrote a letter to the newly appointed general, part of which stated, I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator.

[8]During the spring of 1863, Hooker established a reputation as an outstanding administrator and restored the morale of his soldiers, which had plummeted to a new low under Burnside.

Other orders addressed the need to stem rising desertion (one from Lincoln combined with incoming mail review, the ability to shoot deserters, and better camp picket lines), more and better drills, stronger officer training, and for the first time, combining the federal cavalry into a single corps.

Stone did not receive a command upon his release, mostly due to political pressures, which left him militarily exiled and disgraced.

It is a point to remember because to speak up for General Stone took moral courage, a quality which Joe Hooker is rarely accused of possessing.

He first planned to send his cavalry corps deep into the enemy's rear, disrupting supply lines and distracting him from the main attack.

Part of Hooker's failure can be attributed to an encounter with a cannonball; while he was standing on the porch of his headquarters, the missile struck a wooden column against which he was leaning, initially knocking him senseless, and then putting him out of action for the rest of the day with a concussion.

Several of his subordinate generals, including Couch and Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, openly questioned Hooker's command decisions.

Political winds blew strongly in the following weeks as generals maneuvered to overthrow Hooker or to position themselves if Lincoln decided on his own to do so.

[17] When Hooker got into a dispute with Army headquarters over the status of defensive forces in Harpers Ferry, he impulsively offered his resignation in protest, which was quickly accepted by Lincoln and Halleck.

He was brevetted to major general in the regular army for his success at Chattanooga, but he was disappointed to find that Grant's official report of the battle credited William Tecumseh Sherman's contribution over Hooker's.

He died on October 31, 1879, while on a visit to Garden City, New York, and is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio,[5] his wife's hometown.

"[21] When a newspaper dispatch arrived in New York during the Peninsula Campaign, a typographical error changed the entry "Fighting – Joe Hooker Attacks Rebels" to remove the dash and the name stuck.

Hooker's reputation as a hard-drinking ladies' man was established through rumors in the pre-Civil War Army and has been cited by a number of popular histories.

There is a popular legend that "hooker" as a slang term for a prostitute is derived from his last name[26] because of parties and a lack of military discipline at his headquarters near the Murder Bay district of Washington, DC.

ca. 1860–ca. 1865