Book of Joshua

God's speech foreshadows the major themes of the book: the crossing of the Jordan River and conquest of the land, its distribution, and the imperative need for obedience to the Law.

[11] The Israelites cross the Jordan River through a miraculous intervention of God with the Ark of the Covenant and are circumcised at Gibeath-Haaraloth (translated as hill of foreskins), renamed Gilgal in memory.

An alliance of Amorite kingdoms headed by the Canaanite king of Jerusalem attacks the Gibeonites but they are defeated with Yahweh's miraculous help of stopping the Sun and the Moon, and hurling down large hailstones (Joshua 10:10–14).

A powerful multi-national (or more accurately, multi-ethnic) coalition headed by the king of Hazor, the most important northern city, is defeated at the Battle of the Waters of Merom with Yahweh's help.

The list of the 31 kings is quasi-tabular: Having described how the Israelites and Joshua have carried out the first of their God's commands, the narrative now turns to the second: to "put the people in possession of the land."

[35] The Book of Joshua closes with three concluding items (referred to in the Jerusalem Bible as "Two Additions"):[36] There were no Levitical cities given to the descendants of Aaron in Ephraim, so theologians Carl Friedrich Keil and Franz Delitzsch supposed the land may have been at Geba in the territory of the Tribe of Benjamin: "the situation, 'upon the mountains of Ephraim', is not at variance with this view, as these mountains extended, according to Judges 4:5, etc., far into the territory of Benjamin".

[46] Noth was a student of Albrecht Alt, who emphasized form criticism (whose pioneer had been Hermann Gunkel in the 19th century) and the importance of etiology.

Archaeological evidence in the 1930s showed that the city of Ai, an early target for conquest in the putative Joshua account, had existed and been destroyed, but in the 22nd century BCE.

[50][51] In 1955, G. Ernest Wright discussed the correlation of archaeological data to the early Israelite campaigns, which he divided into three phases per the Book of Joshua.

He pointed to two sets of archaeological findings that "seem to suggest that the biblical account is in general correct regarding the nature of the late thirteenth and twelfth-eleventh centuries in the country" (i.e., "a period of tremendous violence").

[52] Archaeologist Amnon Ben-Tor of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who replaced Yadin as the supervisor of excavations at Hazor in 1990, believed that recently unearthed evidence of violent destruction by burning verifies the Biblical account of the city's conquest by the Israelites.

[53] In 2012, a team led by Ben-Tor and Sharon Zuckerman discovered a scorched palace from the 13th century BC in whose storerooms they found 3,400-year-old ewers holding burned crops.

[54] Sharon Zuckerman did not agree with Ben-Tor's theory, and claimed that the burning was the result of the city's numerous factions opposing each other with excessive force.

[55] In her commentary for the Westminster Bible Companion series, Carolyn Pressler suggested that readers of Joshua should give priority to its theological message ("what passages teach about God") and be aware of what these would have meant to audiences in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE.

[56]: 5–6 Richard Nelson explained that the needs of the centralised monarchy favoured a single story of origins, combining old traditions of an exodus from Egypt, belief in a national god as "divine warrior," and explanations for ruined cities, social stratification and ethnic groups, and contemporary tribes.

[57]: 5 Lester L. Grabbe states that when he was studying for his doctorate (more than three decades before 2007), the "substantial historicity" of the Bible's stories of the patriarchs and the conquest of Canaan was widely accepted, but today it is hard to find a historian who still believes in it.

[58] According to Ann E. Killebrew, "Most scholars today accept that the majority of the conquest narratives in the book of Joshua are devoid of historical reality".

To be sure, there are far more conservative historians who try to defend the historicity of the entire biblical account beginning with Abraham, but their work rests on confessional presuppositions and is an exercise in apologetics rather than historiography.

[78]: 162 The Book of Joshua takes forward Deuteronomy's theme of Israel as a single people worshipping Yahweh in the land God has given them.

[42]: 11 The introduction to Deuteronomy recalled how Yahweh had given the land to the Israelites but then withdrew the gift when Israel showed fear and only Joshua and Caleb had trusted in God.

[10]: 175 "The extermination of the nations glorifies Yahweh as a warrior and promotes Israel's claim to the land," while their continued survival "explores the themes of disobedience and penalty and looks forward to the story told in Judges and Kings.

Miller writes further that the "Deuteronomistic history in Joshua through Second Kings is a story of constant or recurring apostasy" and that for the Israelites, maintaining their allegiance with Yahweh "required, in their sight, removal of all temptation.

Joshua's two final addresses challenge the Israel of the future (the readers of the story) to obey the most important command of all, to worship Yahweh and no other gods.

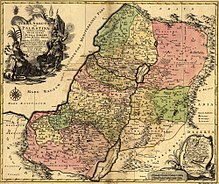

[84] Some of the parallels with Moses can be seen in the following, and not exhaustive, list:[10]: 174 The Book of Joshua deals with the conquest of the Land of Israel and its settlement, which are politically charged issues in Israeli society.

In her article "The Rise and Fall of the Book of Joshua in Public Education in the Light of Ideological Changes in Israeli Society," Israeli biblical scholar Leah Mazor analyzes the history of the book and reveals a complex system of references to it expressed in a wide range of responses, often extreme, moving from narrow-minded admiration, through embarrassment and thunderous silence to a bitter and poignant critique.

[98] The changes in the status of the Book of Joshua, she shows, are the manifestations of the ongoing dialogue that Israeli society has with its cultural heritage, with its history, with the Zionist idea, and with the need to redefine its identity.

David Ben-Gurion saw in the war narrative of Joshua an ideal basis for a unifying national myth for the State of Israel, framed against a common enemy, the Arabs.

For example, Michael Prior criticizes the use of the campaign in Joshua to favor "colonial enterprises" (in general, not only Zionism), which have been interpreted as validating ethnic cleansing.

[101] A related moral condemnation can be seen in "The political sacralization of imperial genocide: contextualizing Timothy Dwight's The Conquest of Canaan" by Bill Templer.

[104] Harvard Bible professor and conservative Rabbi Shaye J. D. Cohen stated he is not happy with the genocide chapters being part of the Torah, and he would remove those from it, if it were his choice.