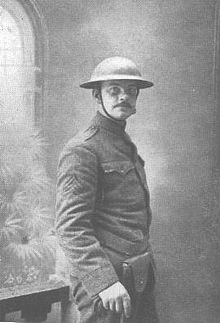

Joyce Kilmer

Though a prolific poet whose works celebrated the common beauty of the natural world as well as his Catholic faith, Kilmer was also a journalist, literary critic, lecturer, and editor.

At the time of his deployment to Europe during World War I, Kilmer was considered the leading American Catholic poet and lecturer of his generation, whom critics often compared to British contemporaries G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936) and Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953).

Kilmer was born December 6, 1886, in New Brunswick, New Jersey,[5] the fourth and youngest child,[note 1] of Annie Ellen Kilburn (1849–1932), a minor writer and composer,[4][6] and Dr. Frederick Barnett Kilmer (1851–1934), a physician and analytical chemist employed by the Johnson and Johnson Company and inventor of the company's baby powder.

By June 1909, Kilmer had abandoned any aspirations to continue teaching and relocated to New York City, where he focused solely on developing a career as a writer.

This was a job at which one would ordinarily earn ten to twelve dollars a week, but Kilmer attacked the task with such vigor and speed that it was soon thought wisest to put him on a regular salary.

According to Robert Holliday, Kilmer "frequently neglected to make any preparation for his speeches, not even choosing a subject until the beginning of the dinner which was to culminate in a specimen of his oratory.

His constant research for the dictionary, and, later on, for his New York Times articles, must have given him a store of knowledge at his fingertips to be produced at a moment's notice for these emergencies.

"[1]: p.21 [15] When the Kilmers' daughter Rose (1912–1917) was stricken with poliomyelitis (also known as infantile paralysis) shortly after birth,[4] they turned to their religious faith for comfort.

His close friend and editor Robert Holliday wrote that it "is not an unsupported assertion to say that he was in his time and place the laureate of the Catholic Church.

Over the next few years, Kilmer was prolific in his output, managing an intense schedule of lectures, publishing a large number of essays and literary criticism, and writing poetry.

In 1916 and 1917, before the American entry into World War I, Kilmer would publish four books: The Circus and Other Essays (1916), a series of interviews with literary personages entitled Literature in the Making (1917), Main Street and Other Poems (1917), and Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets (1917).

[4] In the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland, Kilmer helped organize a large memorial service in New Yorks Central Park for those who died in that conflict.

[18] In April 1917, a few days after the United States entered World War I, Kilmer enlisted in the Seventh Regiment of the New York National Guard.

The regiment arrived in France in November 1917, and Kilmer wrote to his wife that he had not written "anything in prose or verse since I got here—except statistics—but I've stored up a lot of memories to turn into copy when I get a chance.

At the time, this was a relatively quiet sector of the front, but the first battalion was struck by a German heavy artillery bombardment on the afternoon of March 7, 1918, that buried 21 men of the unit, killing 19 (of which 14 remained entombed).

According to military records, Kilmer died on the battlefield near Muercy Farm, beside the Ourcq River near the village of Seringes-et-Nesles, in France, on July 30, 1918, at the age of 31.

[24] Kilmer was buried in the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial, near Fere-en-Tardenois, Aisne, Picardy, France just across the road and stream from the farm where he was killed.

According to Robert Holliday, Kilmer's friend and editor, "Trees" speaks "with authentic song to the simplest of hearts" and that "(t)he exquisite title poem now so universally known, made his reputation more than all the rest he had written put together.

One of the best known parodies is "Song of the Open Road" by American humorist and poet Ogden Nash (1902–1971): Kilmer's early works were inspired by, and were imitative of, the poetry of Algernon Charles Swinburne, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Ernest Dowson, Aubrey Beardsley, and William Butler Yeats (and the Celtic Revival).

He has not the rich vocabulary, the decorative erudition, the Shelleyan enthusiasm, which distinguish the Sister Songs and the Hound of Heaven, but he has a classical simplicity, a restraint and sincerity which make his poems satisfying.

During this time he did considerable research into 16th and 17th century Anglican poets as well as metaphysical, or mystic poets of that time, including George Herbert, Thomas Traherne, Robert Herrick, Bishop Coxe, and Robert Stephen Hawker (the eccentric vicar of the Church of Saint Morwenna and Saint John the Baptist at Morwenstow in Cornwall)—the latter whom he referred to as "a coast life-guard in a cassock."

[1]: p.19 Critics compared Kilmer to British Catholic writers Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton—suggesting that his reputation might have risen to the level where he would have been considered their American counterpart if not for his untimely death.

Only a very few of his poems have appeared in anthologies, and with the exception of "Trees"—and to a much lesser extent "Rouge Bouquet" (1917–1918)—almost none have obtained lasting widespread popularity.

[1]: p.26 [1]: p.40 The entire corpus of Kilmer's work was produced between 1909 and 1918 when Romanticism and sentimental lyric poetry fell out of favor and Modernism took root—especially with the influence of the Lost Generation.