Jutes

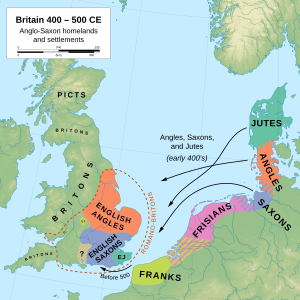

During the period after the Roman occupation and before the Norman conquest, people of Germanic descent arrived in Britain, ultimately forming England.

[4][5] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how the brothers Hengist and Horsa in the year 449 were invited to Sub-Roman Britain by Vortigern to assist his forces in fighting the Picts.

The Saxons populated Essex, Sussex and Wessex; the Jutes Kent, the Isle of Wight and Hampshire; and the Angles East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria (leaving their original homeland, Angeln, deserted).

[11] Towards the end of the Roman occupation of England, raids on the east coast became more intense and the expedient adopted by Romano-British leaders was to enlist the help of mercenaries to whom they ceded territory.

[13][14] One alternative hypothesis to the foundation legend suggests, because previously inhabited sites on the Frisian and north German coasts had been rendered uninhabitable by flooding[e], that the migration was due to displacement.

Under this alternative hypothesis, the British provided land for the refugees to settle on in return for peaceful coexistence and military cooperation.

Vessels going from Jutland to Britain probably would have sailed along the coastal regions of Lower Saxony and the Netherlands before crossing the English Channel.

[16] It is likely that the Jutes initially inhabited Kent and from there they occupied the Isle of Wight, southern Hampshire and also possibly the area around Hastings in East Sussex (Haestingas).

Therefore, it is possible that the German folk arriving in the 5th century that landed in the Selsey area would have been directed north to Southampton Water.

He must have come into conflict with Mercia, because in 676 the Mercian king Æthelred invaded Kent and according to Bede: In the year of our Lord's incarnation 676, when Ethelred, king of the Mercians, ravaged Kent with a powerful army, and profaned churches and monasteries, without regard to religion, or the fear of God, he among the rest destroyed the city of RochesterIn 681 Wulfhere of Mercia advanced into southern Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.

Ultimately, Eadric revolted against his uncle and with help from a South Saxon army in about 685, was able to kill Hlothhere, and replace him as ruler of Kent.

[36] Brooches and bracteates found in east Kent, the Isle of Wight and southern Hampshire showed a strong Frankish[j] and North Sea influence from the mid-fifth century to the late sixth century compared to north German styles found elsewhere in Anglo-Saxon England.

Æthelberht rebuilt an old Romano-British structure and dedicated it to St Martin allowing Bertha to continue practising her Christian faith.

[46] The lack of archaeological grave evidence in the land of the Haestingas is seen as supporting the hypothesis that the peoples there would have been Christian Jutes who had migrated from Kent.

[19] In contrast to Kent, the Isle of Wight was the last area of Anglo-Saxon England to be evangelised in 686, when Cædwalla of Wessex invaded the island, killing the local king Arwald and his brothers.

[50] The popular reason given for the practice remaining so long is due to the "Swanscombe Legend"; according to this, Kent made a deal with William the Conqueror whereby he would allow them to keep local customs in return for peace.

[1] The Jutes have also been identified with the Eotenas (ēotenas) involved in the Frisian conflict with the Danes as described in the Finnesburg episode in the Old English poem Beowulf.

[53] Theudebert, king of the Franks, wrote to the Emperor Justinian and in the letter claimed that he had lordship over a nation called the Saxones Eucii.

The Euthiones were located somewhere in northern Francia, modern day Flanders, an area of the European mainland opposite to Kent.

[63] While there is no definitive proof that the Frisians and Jutes were the same people, there is compelling evidence suggesting that they were either a single group known by different names or closely related tribes with overlapping territories, cultures, and identities.

In several Old English and early medieval sources, such as the Finnsburg Fragment and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the terms "Frisians" and "Jutes" appear to be used interchangeably.

[64] Moreover, archaeological findings point to strong cultural similarities between the two groups, as burial practices, material goods (such as weapons, pottery, and jewelry), and settlement patterns in Jutland and Frisian territories show remarkable parallels.

[70] Based on Bede's description of where the Jutes settled, Kentish was spoken in what are now the modern-day counties of Kent, Surrey, southern Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.