Stellar classification

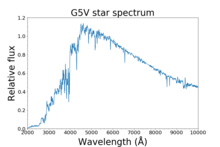

Electromagnetic radiation from the star is analyzed by splitting it with a prism or diffraction grating into a spectrum exhibiting the rainbow of colors interspersed with spectral lines.

The spectral class of a star is a short code primarily summarizing the ionization state, giving an objective measure of the photosphere's temperature.

The full spectral class for the Sun is then G2V, indicating a main-sequence star with a surface temperature around 5,800 K. The conventional colour description takes into account only the peak of the stellar spectrum.

Excluding colour-contrast effects in dim light, in typical viewing conditions there are no green, cyan, indigo, or violet stars.

[33] Additional nomenclature, in the form of lower-case letters, can follow the spectral type to indicate peculiar features of the spectrum.

The reason for the odd arrangement of letters in the Harvard classification is historical, having evolved from the earlier Secchi classes and been progressively modified as understanding improved.

In the 1880s, the astronomer Edward C. Pickering began to make a survey of stellar spectra at the Harvard College Observatory, using the objective-prism method.

[53] With the help of the Harvard computers, especially Williamina Fleming, the first iteration of the Henry Draper catalogue was devised to replace the Roman-numeral scheme established by Angelo Secchi.

[56][57] Because the 22 Roman numeral groupings did not account for additional variations in spectra, three additional divisions were made to further specify differences: Lowercase letters were added to differentiate relative line appearance in spectra; the lines were defined as:[58] Antonia Maury published her own stellar classification catalogue in 1897 called "Spectra of Bright Stars Photographed with the 11 inch Draper Telescope as Part of the Henry Draper Memorial", which included 4,800 photographs and Maury's analyses of 681 bright northern stars.

This system was developed through the analysis of spectra on photographic plates, which could convert light emanated from stars into a readable spectrum.

This mechanism provided ages of the Sun that were much smaller than what is observed in the geologic record, and was rendered obsolete by the discovery that stars are powered by nuclear fusion.

Higher-mass O-type stars do not retain extensive atmospheres due to the extreme velocity of their stellar wind, which may reach 2,000 km/s.

Thus, due to the low probability of kinematic interaction during their lifetime, they are unable to stray far from the area in which they formed, apart from runaway stars.

Mainstream theories (those rooted in lower harmful radioactivity and star longevity) would thus suggest such stars have the optimal chances of heavily evolved life developing on orbiting planets (if such life is directly analogous to Earth's) due to a broad habitable zone yet much lower harmful periods of emission compared to those with the broadest such zones.

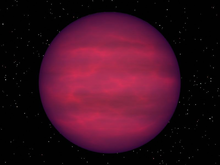

[c][f][11] However, class M main-sequence stars (red dwarfs) have such low luminosities that none are bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye, unless under exceptional conditions.

They are thought to mostly be dying supergiants with their hydrogen layers blown away by stellar winds, thereby directly exposing their hot helium shells.

Class WR is further divided into subclasses according to the relative strength of nitrogen and carbon emission lines in their spectra (and outer layers).

However, it may be possible for these L-type supergiants to form through stellar collisions, an example of which is V838 Monocerotis while in the height of its luminous red nova eruption.

[100] Although such dwarfs have been modelled[101] and detected within forty light-years by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)[87][102][103][104][105] there is no well-defined spectral sequence yet and no prototypes.

[102][103][110] Parallax measurements have, however, since shown that its luminosity is inconsistent with it being colder than ~400 K. The coolest Y dwarf currently known is WISE 0855−0714 with an approximate temperature of 250 K, and a mass just seven times that of Jupiter.

[106] Young brown dwarfs have low surface gravities because they have larger radii and lower masses compared to the field stars of similar spectral type.

The peculiar suffix is still used for other features that are unusual and summarizes different properties, indicative of low surface gravity, subdwarfs and unresolved binaries.

A number following a slash is a more-recent but less-common scheme designed to represent the ratio of carbon to oxygen on a scale of 1 to 10, where a 0 would be an MS star.

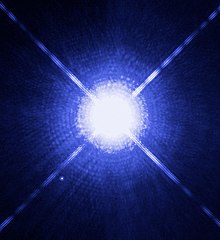

The class D (for Degenerate) is the modern classification used for white dwarfs—low-mass stars that are no longer undergoing nuclear fusion and have shrunk to planetary size, slowly cooling down.

Included in the category are white dwarfs, and as can be seen from the radically different classification scheme for class D, stellar remnants are difficult to fit into the MK system.

Planetary nebulae are dynamic and tend to quickly fade in brightness as the progenitor star transitions to the white dwarf branch.

These neutrinos carry away so much heat energy that after only a few years the temperature of an isolated neutron star falls from the order of billions to only around a million Kelvin.

While humans may eventually be able to colonize any kind of stellar habitat, this section will address the probability of life arising around other stars.

Working from these constraints and the problems of having an empirical sample set of only one, the range of stars that are predicted to be able to support life is limited by a few factors.

[128] While there are many problems facing life on red dwarfs, many astronomers continue to model these systems due to their sheer numbers and longevity.