Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

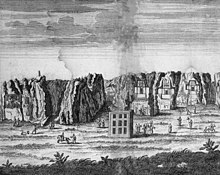

Ka'ba-ye Zartosht (Persian: کعبه زرتشت), also called the Cube of Zoroaster, is a rectangular stepped stone structure in the Naqsh-e Rustam compound beside Zangiabad village in Marvdasht county in Fars, Iran.

The limestone blocks were brought from Mount Sivand, where they were quarried in a place called Na'l Shekan ("horseshoe breaker"), to Naqsh-e Rustam to build the Ka'ba.

Each of those stones are 7.30 metres (24.0 ft) long, connected to each other by dovetail joints, and the chipping method used to form them has given the roof the shape of a short pyramid.

[2] To prevent the finished building from becoming too simple or monochrome, its creators added two architectural diversities: firstly, forming double-edged shelves from one or two flat plates of grey-black stone and placing them on the walls; secondly, carving small rectangular pits into the upper and middle sections of the outer walls that give a more delicate appearance to the tower's faces.

The ceiling of the structure is smooth and flat on the inside, but its roof has a bilateral slope that begins from the line in the middle of the rooftop on the outside, creating the pyramid-like appearance previously mentioned.

Much of the available evidence shows that it was built in the early Achaemenid era; the most important evidence for this dating is as follows:[2] Carsten Niebuhr, who had visited the structure in 1765, writes: "Opposite the mountain that has the mausoleums and petroglyphs of Rostam's braveries, a small structure is built of white stone that is covered by only two pieces of large stones.

"[9] Jane Dieulafoy, who visited Iran in 1881, also reports in her travel journal: "...and then we saw a quadrilateral structure that was placed opposite the walls of the cliff.

[11] Additionally, the compound was probed by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago under the leadership of Erich Schmidt in several seasons between 1936 and 1939, finding important works like the Middle Persian version of the Great Inscription of Shapur I, which was written on the wall of the structure.

[13] Another group including Henry Rawlinson and Walter Henning believe that the structure was the treasury and the place for keeping religious documents and Avesta.

[2] Erich Friedrich Schmidt says about the importance of the structure:[2]The outstanding effort that was necessary for creating this architectural masterpiece, was only used for building a single and dark chamber.

Besides, the fact that they did or could close the only entrance door of a structure with a heavy and two-panel door, makes it clear that its content should be kept safe from robbery and pollution.Engelbert Kaempfer first proposed the assumption of being a fire temple or fireplace; and following him, James Justinian Morier and Robert Ker Porter supported the view in the early nineteenth century.

I returned the pastures, flocks, slaves and houses that Gaumata had taken to the people..."[17] Thus, there were some "temples" in the periods of Cyrus II and Cambyses II that Gaumata destroyed and Darius rebuilt them the same way; and since "Solomon's Prison" in Pasargadae is belonging to the first Achaemenid era and destroyed, and its exact copy was built in Naqsh-e Rustam in Darius's period, it should be concluded that those two structures are the mentioned temples in the Behistun Inscription; and since any temple in Persia during Darius's period could not be anything other than the holy fire, those were all fireplaces;[2] besides, Ka'ba-ye Zartosht has been conserved well even after the Achaemenid era and was not surrounded by soil and stones; and in the beginning of the Sasanian era, Shapur I composed the most important document of the Sasanian history on it and Kartir wrote a religious document on it.

[2] Because fire requires oxygen and the inside of the Ka'ba is built in a way that even an oil lamp can not glow more than a few hours when the door and the large stone entrance are sealed.

[4][12] The structure on the coins of Persian kings can not be Ka'ba-ye Zartosht; for the mentioned picture on the coins was not higher than 2 metres (6 ft 7 in), had a two-stair platform and no stairway is seen below its doorway; its entrance door is much larger relative to the structure than that of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht; its ceiling has no steepness, enough to be put three fireboxes on; there is no distance between its doorway and the ceiling; it has no crowns or portals; and the dents showing the heads of its arrows are not more than six.

Welfram Klyse and David Stronach believe that the Achaemenid structures in Pasargadae and Naqsh-e Rustam might have been influenced by Urartian art in the tower-like temples of Urartu.

Besides that, Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is a near to the mausoleums that were built at the same time; and all of them were later separated from the other parts of Naqsh-e Rustam by a chain of fortifications, indicating that they were all originally the same type and had similar applications.

Rawlinson's reasons were the accurate architecture and the proper size of the chamber, its sole door being heavy and solid and that it was difficult to reach inside the structure.

Some argue that the chamber of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is too small to keep the Avesta and other religious books and royal flags; a wider and larger site was necessary for such an intention.

In addition, some point out the relatively remote location of the structure suggests another use, as the various palaces of the Achaemenid shahanshahs as well as other official and governmental buildings would be better suited for keeping the Avesta and royal flags.

[2] In Shapur's Inscription, which should be considered the "Revolution Resolution" of the Sassanian dynasty,[29] he first introduces himself and mentions the regions he ruled and then describes the Persian-Roman Wars and indicates the defeat and death of Marcus Antonius Gordianus, after whom the Roman forces proclaimed Marcus Julius Philippus the emperor; and the latter paid Shapur a compensation equal to half a million gold dinars for reprieve and returned to his homeland.

[14] Kartir's Inscription, which is situated below the Sassanian Middle Persian inscription of Shapur's, is written during Bahram II's reign and around 280 A.D.[2] He first introduces himself and then mentions his ranks and titles during the periods of the previous kings and says that he had the Herbad title during Shapur I's period and was appointed as "the grand master of all priests by Shahanshah Shapur I" and had the honor of receiving a hat and a belt by the shahanshah in Hormizd I's period and has achieved an increasing power and acquired the nickname "The Priest of Ahura Mazda, the god of gods".

[9][31] Then, Kartir mentions his religious activities like fighting other religions such as Christianity, Manichaeism, Mandaeism, Judaism, Buddhism and Zoroastrian heresy and remarks founding fire temples and allocation of donations for them.

[9] He also talks about correcting the priests that were, in his opinion, perverted and mentions the list of the states that were conquered by Persia during Shapur I's period and eventually the inscription ends with a prayer.