Sasanian Empire

[11][12] Upon succeeding the Parthians in the third century, the Sasanian dynasty re-established the Persian nation as a major power in late antiquity, and also continued to compete extensively with the neighbouring Roman Empire.

After defeating Artabanus IV of Parthia during the Battle of Hormozdgan in 224, Ardashir's dynasty replaced that of the Arsacids and promptly set out to restore the legacy of the Achaemenid Empire by expanding the newly acquired Sasanian dominions.

The Sasanian Empire's cultural influence extended far beyond the physical territory that it controlled, impacting regions as distant as Western Europe,[18] Eastern Africa,[19] and China and India.

After establishing his rule over Pars, Ardashir rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighbouring provinces of Kerman, Isfahan, Susiana and Mesene.

Ardashīr began leading campaigns into Greater Khurasan as early as 233, extending his power to Khwarazm in the north and Sistan in the south while capturing lands from Gorgan to Abarshahr, Marw, and as far east as Balkh.

He ordered the construction of the first dam bridge in Iran and founded many cities, some settled in part by emigrants from the Roman territories, including Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sassanid rule.

Following Hormizd II's death, northern Arabs started to ravage and plunder the western cities of the empire, even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings.

From around 370, however, towards the end of the reign of Shapur II, the Sasanians lost the control of Bactria to invaders from the north: first the Kidarites, then the Hephthalites and finally the Alchon Huns, who would follow up with an invasion of India.

At the beginning of his reign in 441, Yazdegerd II assembled an army of soldiers from various nations, including his Indian allies, and attacked the Byzantine Empire, but peace was soon restored after some small-scale fighting.

[74] Kavad succeeded in restoring order in the interior and fought with general success against the Eastern Romans, founded several cities, some of which were named after him, and began to regulate taxation and internal administration.

Capitalizing on this success, the Persians then ravaged Syria, causing Justin II to agree to make annual payments in exchange for a five-year truce on the Mesopotamian front, although the war continued elsewhere.

[79] After Maurice was overthrown and killed by Phocas (602–610) in 602, however, Khosrow II used the murder of his benefactor as a pretext to begin a new invasion, which benefited from continuing civil war in the Byzantine Empire and met little effective resistance.

[80] The impact of Heraclius's victories, the devastation of the richest territories of the Sassanid Empire, and the humiliating destruction of high-profile targets such as Ganzak and Dastagerd fatally undermined Khosrow's prestige and his support among the Persian aristocracy.

The Sassanids were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the increasing power of the provincial landholders, and a rapid turnover of rulers, facilitating the Islamic conquest of Persia.

Yazdegerd was a boy at the mercy of his advisers and incapable of uniting a vast country crumbling into small feudal kingdoms, despite the fact that the Byzantines, under similar pressure from the newly expansive Arabs, were no longer a threat.

Caliph Abu Bakr's commander Khalid ibn Walid, once one of Muhammad's chosen companions-in-arms and leader of the Arab army, moved to capture Iraq in a series of lightning battles.

In 637, a Muslim army under the Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattāb defeated a larger Persian force led by General Rostam Farrokhzad at the plains of al-Qādisiyyah, and then advanced on Ctesiphon, which fell after a prolonged siege.

The abrupt fall of the Sassanid Empire was completed in a period of just five years, and most of its territory was absorbed into the Islamic caliphate; however, many Iranian cities resisted and fought against the invaders several times.

[85] It is believed that the following dynasties and noble families had ancestors among the Sasanian rulers: The Sassanids established an empire roughly within the frontiers achieved by the Parthian Arsacids, with the capital at Ctesiphon in the Asoristan province.

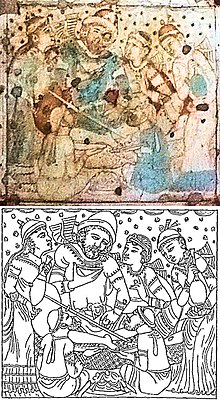

Each unit was headed by an officer called a "Paygan-salar", which meant "commander of the infantry" and their main task was to guard the baggage train, serve as pages to the Asvaran (a higher rank), storm fortification walls, undertake entrenchment projects, and excavate mines.

[103] The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus's description of Shapur II's clibanarii cavalry manifestly shows how heavily equipped it was, and how only a portion were spear equipped: All the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff-joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces were so skillfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath.

In general, over the span of the centuries, in the west, Sassanid territory abutted that of the large and stable Roman state, but to the east, its nearest neighbors were the Kushan Empire and nomadic tribes such as the White Huns.

On the eastern side of the Caspian Sea, the Sassanians erected the Great Wall of Gorgan, a 200 km-long defensive structure probably aimed to protect the empire from northern peoples, such as the White Huns.

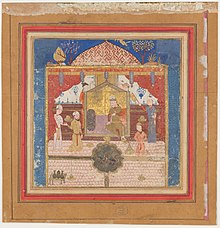

[116] This can be credited to, among other things, the Sasanians founding and re-founding a number of cities, which is talked about in the surviving Middle Persian text Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr (the provincial capitals of Iran).

During his reign, many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the Karnamak-i Artaxshir-i Papakan (Deeds of Ardashir), a mixture of history and romance that served as the basis of the Iranian national epic, the Shahnameh.

[21] According to Will Durant: Sasanian art exported its forms and motifs eastward into India, Turkestan and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt and Spain.

Silks, embroideries, brocades, damasks, tapestries, chair covers, canopies, tents and rugs were woven with patience and masterly skill, and were dyed in warm tints of yellow, blue and green.

Stucco wall decorations appear at Bishapur, but better examples are preserved from Chal Tarkhan near Rey (late Sasanian or early Islamic in date), and from Ctesiphon and Kish in Mesopotamia.

Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India.

To some extent Kartir was an iconoclast and took it upon himself to help establish numerous Bahram fires throughout Iran in the place of the 'bagins / ayazans' (monuments and temples containing images and idols of cult-deities) that had proliferated during the Parthian era.

Obverse: Bearded facing head, wearing diadem and Parthian-style tiara, legend "The divine Ardaxir, king" in Pahlavi.

Reverse: Bearded head of Papak , wearing diadem and Parthian-style tiara, legend "son of the divinity Papak, king" in Pahlavi.

and

Alchono

(

αλχοννο

) in

Bactrian script

on the

obverse

. Dated 400–440.

[

49

]

and

Alchono

(

αλχοννο

) in

Bactrian script

on the

obverse

. Dated 400–440.

[

49

]