Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

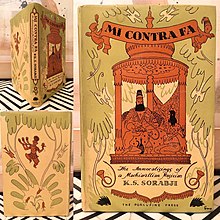

His compositions received little exposure in those years and he remained in public view mainly through his writings, which include the books Around Music and Mi contra fa: The Immoralisings of a Machiavellian Musician.

He drew on such diverse influences as Ferruccio Busoni, Claude Debussy and Karol Szymanowski and developed a style blending baroque forms with frequent polyrhythms, interplay of tonal and atonal elements and lavish ornamentation.

Later that year, Sorabji joined Chisholm's recently created Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music,[35] whose concerts featured a number of distinguished composers and musicians.

[37][38] He came to Glasgow four times and played some of the longest works he had written to date: he premiered Opus clavicembalisticum and his Fourth Sonata[n 4] in 1930 and his Toccata seconda in 1936, and he gave a performance of Nocturne, "Jāmī" in 1931.

[45] His withdrawal from the world of music has usually been ascribed to Tobin's recital,[46] but other reasons have been put forward for his decision, including the deaths of people he admired (such as Busoni) and the increasing prominence of Igor Stravinsky and twelve-tone composition.

[61] Many of Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Studies (1940–1944) were written during German bombings, and he composed during the night and early morning in his home at Clarence Gate Gardens (Marylebone, London) even as most other blocks were abandoned.

[66] While Sorabji felt despised by the English music establishment,[67] the main target of his ire was London, which he called the "International Human Rubbish dump"[68] and "Spivopolis" (a reference to the term spiv).

After the Messa grande sinfonica (1955–61)—which comprises 1,001 pages of orchestral score[90]—was completed, Sorabji wrote he had no desire to continue composing, and in August 1962, he suggested he might abandon composition and destroy his extant manuscripts.

[98] Hinton also persuaded Sorabji to give Yonty Solomon permission to play his works in public, which was granted on 24 March 1976 and marked the end of the "ban", although another pianist, Michael Habermann, may have received tentative approval at an earlier date.

[104] Shortly after, Sorabji received a commission from Gentieu (who acted on behalf of the Philadelphia branch of the Delius Society) and fulfilled it by writing Il tessuto d'arabeschi (1979) for flute and string quartet.

[105] Sorabji completed his final piece, Due sutras sul nome dell'amico Alexis, in 1984,[106] and stopped composing afterwards because of his failing eyesight and struggle to physically write.

The papal connection ... was a particular favourite and as much as Sorabji detested being spotlighted in a large group, he was perfectly content in more intimate situations bringing direct attention to his ring or his thorny attitude regarding the ban on his music.

[138] In March 1987, they moved into Marley House Nursing Home, where Sorabji called him "darling" and complimented him on his looks before Best's death on 29 February 1988, an event described as a blow to the composer.

[150] In an unpublished text titled The Fruits of Misanthropy, he justified his reclusiveness by saying, "my own failings are so great that they are as much as I can put up with in comfort—those of other people superadded I find a burden quite intolerable".

In his early life, he denounced it for fuelling war and deemed it a hypocritical religion,[162] though he later voiced his admiration for the Catholic Church and attributed the most valuable parts of European civilisation to it.

[183] The nocturnes are generally considered to be among Sorabji's most accessible works,[184] and they are also some of his most highly regarded; they have been described by Habermann as "the most successful and beautiful of [his] compositions",[184] and by the pianist Fredrik Ullén as "perhaps ... his most personal and original contribution as a composer".

The subjects can lack the frequent changes of direction present in most melodic writing, and some of the fugues are among the longest ever penned, one being the two-hour "Fuga triplex" that closes the Second Symphony for Organ.

[217] Sorabji's next two pieces, Benedizione di San Francesco d'Assisi and Symphonia brevis for Piano, were written in 1973, the year after the two first met, and marked the beginning of what has been identified as his "late style",[218] one characterised by thinner textures and greater use of extended harmonies.

[225][226][227][n 18] His later work was also significantly influenced by the virtuoso writing of Charles-Valentin Alkan and Leopold Godowsky, Max Reger's use of counterpoint, and the impressionist harmonies of Claude Debussy and Karol Szymanowski.

According to Habermann, it manifests itself in the following ways: highly supple and irregular rhythmic patterns, abundant ornamentation, an improvisatory and timeless feel, frequent polyrhythmic writing and the vast dimensions of some of his compositions.

[249] Sorabji, who claimed to be of Spanish-Sicilian ancestry, composed pieces that reflect an enthusiasm for Southern European cultures, such as Fantasia ispanica, Rosario d'arabeschi and Passeggiata veneziana.

[191] While Sorabji wrote pieces of standard or even minute dimensions,[6][257] his largest works (for which he is perhaps best known)[114] call for skills and stamina beyond the reach of most performers;[258] examples include his Piano Sonata No.

[267] Sorabji achieved this in part by using widely spaced chords rooted in triadic harmonies and pedal points in the low registers, which act as sound cushions and soften dissonances in the upper voices.

[112] The unusual features of Sorabji's music and the "ban" resulted in idiosyncrasies in his notation: a shortage of interpretative directions, the relative absence of time signatures (except in his chamber and orchestral works) and the non-systematic use of bar lines.

[286] Contemporary reviews noted Sorabji's tendency to rush the music and his lack of patience with quiet passages,[287] and the private recordings that he made in the 1960s contain substantial deviations from his scores, attributed in part to his impatience and uninterest in playing clearly and accurately.

[310][311] For Sorabji, transcription enabled older material to undergo transformation to create an entirely new work (which he did in his pastiches), and he saw the practice as a way to enrich and uncover the ideas concealed in a piece.

[326] He rejected serialism and twelve-tone composition, as he considered both to be based on artificial precepts,[327] denounced Schoenberg's vocal writing and use of Sprechgesang,[328] and even criticised his later tonal works and transcriptions.

[342][343] Hugh MacDiarmid ranked him as one of the four greatest minds Great Britain had produced in his lifetime, eclipsed only by T. S. Eliot,[344] and the composer and conductor Mervyn Vicars put Sorabji next to Richard Wagner, who he believed "had one of the finest brains since Da Vinci".

[354] Abrahams finds that Sorabji's musical production exhibits enormous "variety and imagination" and calls him "one of the few composers of the time to be able to develop a unique personal style and employ it freely at any scale he chose".

[379][380][n 24] The mixing of chords with different root notes and the use of nested tuplets, both present throughout Sorabji's works, have been described as anticipating Messiaen's music and Stockhausen's Klavierstücke (1952–2004) respectively by several decades.