Kamajiro Hotta

[3] Due to Hotta's unprecedented financial success growing and selling asparagus, many Japanese immigrant farmers in the area attempted to follow in his footsteps.

[3] Following the passage of anti-Japanese legislation in California such as the Alien Land Law of 1913, the amendment to the Alien Land Law in 1920, and the 1923 United States Supreme Court case ruling against cropping contracts, Hotta stepped down as president of the Japanese Producers Association and returned to his hometown in Japan where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Japanese immigration to the United States was primarily triggered by economic stagnation, high unemployment rates, and poor living conditions because of the rapidly increasing population in Japan.

[5] These reasons caused a huge population increase of Japanese immigrants in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with over 127,000 individuals entering between 1901 and 1908.

[14] At the age of 16 years and 11 months, Kamajiro Hotta first arrived in San Francisco on September 23, 1893, on the ship named City of Rio de Janeiro.

[15] Hotta and his peers, including Masayoshi Ota, were leading proponents in increasing the number of Japanese immigrants in Concord County and Walnut Grove.

Immigration records reveal that she had $50 in her possession upon arrival, was literate in Japanese, listed her occupation as “wife,” and was born in Nakayasu Village, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan.

Following his first immigration to the United States at age 17, Kamajiro Hotta quickly obtained work at a local nursery in Acampo, California to cover his newfound living expenses as an independent.

[1] Although he believed that farming would be a highly lucrative career and that he had the work ethic to pull it off, he initially lacked the necessary up front capital to lease his own plot of land.

[3] In 1904, Hotta finally had enough financial capital saved up to abandon his multiple places of employment and begin his full time career as a landowning farmer.

At this time, he and three other Aichi-born Japanese immigrants pooled their money together and purchased three farms as cash tenants in the area surrounding Walnut Grove.

[3] This was a monumental milestone in Hotta's journey to a new kind of life in the United States and position of influence within the farming community of California in the early 20th century.

Unlike the vast majority of leasing agreements of the time period, Hotta's legally binding contract did not include any clauses restricting how to operate his farms.

[2] As a result, he was forced to plant several acres of quicker growing crops like beans and onions to supplement his income and have enough money to pay his bills.

Despite the minimal financial returns that Hotta received from his beans and onions during the years 1905, 1906, and 1907, he was very optimistic about the future because of the 1908 season in which he would be able to harvest and sell asparagus for the first time.

[3] In 1908, Hotta sold his newly grown, first generation asparagus to grocers and farmers markets in the surrounding area for the first time and profited over $2,000 after accounting for all of his yearly expenses.

In 1910, he successfully brokered a business deal with the California Fruit Canners Association in San Francisco to purchase all of his asparagus cultivated between the years 1910 and 1914.

[3] This major increase and crop shift can largely be attributed to Hotta, who the people of Walnut Grove appropriately nicknamed the Asparagus King.

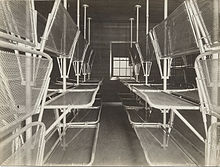

[20] As a result of the rapid growth in asparagus farming in the Walnut Grove area, Japanese immigrant farmers decided that they needed a local organization to help direct the affairs of their newfound industry and coordinate their efforts to maximize crop profits.

[3] During his presidency, he fought relentlessly to land fair asparagus contracts with canneries for local farmers and weaken the overbearing hand of rich, white landowners.

The massive increase of anti-Japanese political and organizational movements in California following Yellow Peril arguments at the time ultimately diminished his influence.

[3] After resigning from being president of the local Japanese Producers Association, Kamajiro Hotta left Walnut Grove and returned to Japan in September 1924.

At this time, he felt as though there were no longer prospects for him as a farmer in the United States and that he would be more successful in Japan with the tens of thousands of dollars that he had accrued.