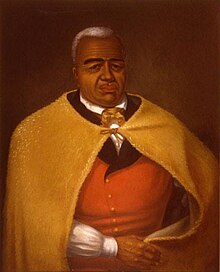

Kamehameha I

Kamehameha (known as Paiʻea at birth),[3] was born to Kekuʻiapoiwa II, the niece of Alapainui, the usurping ruler of Hawaii Island who had killed the two legitimate heirs of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku during civil war.

[9] Regardless of the rumors, Kamehameha was a descendant of Keawe through his mother Kekuʻiapoiwa II; Keōua acknowledged him as his son and he is recognized as such by all the sovereigns[10] and most genealogists.

[12] This dating, however, does not accord with the details of many well-known accounts of his life, such as his fighting as a warrior with his uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, or his being of age to father his first children by that time.

[15] Regardless, Abraham Fornander wrote in his book, An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations: "when Kamehameha died in 1819 he was past eighty years old.

[17] In 1888 the Kamakau account was challenged by Samuel C. Damon in the missionary publication; The Friend, deferring to a 1753 dating that was the first mentioned by James Jackson Jarves.

[20][21] On February 10, 1911, the Kamakau version was challenged by the oral history of the Kaha family, as published in newspaper articles also appearing in the Kuoko.

While the kingship was inherited by Kīwalaʻō, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's son, Kamehameha was given a prominent religious position as guardian of the Hawaiian god of war, Kūkaʻilimoku.

Kamehameha and his chiefs took over Konohiki responsibilities and sacred obligations of the districts of Kohala, Kona, and Hāmākua on Hawaiʻi island.

Another major factor in Kamehameha's continued success was the support of Kauai chief Kaʻiana and Captain William Brown of the Butterworth Squadron.

Two westerners who lived on Hawaiʻi island, Isaac Davis and John Young, married native Hawaiian women and assisted Kamehameha.

Fair American was held-up when it was captured by the Spanish and then quickly released in San Blas, north of Panamá.

Sometime later, while docked in Honolua, Maui, a small boat—which was tied to the larger ship, and had a crewman inside—was stolen by native islanders.

Previously, Metcalfe had resorted to violence when he fired muskets into another village near where he had been anchored, ultimately killing some of the residents.

This time, furious, Metcalfe took-aim at Olowalu, ordering all cannons aboard the ship to be moved to one side, facing the island.

Six weeks later, Fair American was stuck near the Kona coast of Hawaii where chief Kameʻeiamoku was living, near Kaʻūpūlehu.

Eleanora waited several days before sailing off, apparently without knowledge of what had happened to Fair American or Metcalfe's son.

Davis and Eleanora's boatswain, John Young, tried to escape, but were treated as chiefs, given wives and settled in Hawaii.

[25] In 1790, while the aliʻi Kahekili II was on Oʻahu, Kamehameha's army invaded Maui with the assistance of John Young and Isaac Davis.

Using cannons from the Fair American, they defeated Maui's army led by Kahekili's son Kalanikūpule at the bloody Battle of Kepaniwai .

[27] In 1790, Keōua Kūʻahuʻula, who came to rule the districts of Kaʻū and Puna, took advantage of Kamehameha's absence in Maui and began raiding the west coast of Hawaii.

A civil war between the two broke out, which ended when Kalanikūpule killed Kāʻeokūlani, taking control of Maui and Molokaʻi.

[30] In a series of skirmishes, Kamehameha's forces pushed Kalanikūpule's men back until they were cornered on the Pali Lookout.

He assigned two divisions of his best warriors to climb to the Pali to attack the cannons from behind; they surprised Kalanikūpule's gunners and took control.

In the spring of 1796, he attempted to continue with his forces to Kauaʻi but he lost many of his canoes in the strong winds and rough seas of the Kaʻieʻie Waho channel.

While in Oʻahu, a large percentage of his force was killed by the maʻi ʻokuʻu epidemic, which was thought to be either cholera or bubonic plague.

His court genealogist and high priest Kalaikuʻahulu was instrumental in the monarch's decision to leave Kaumualiʻi as a tributary king rather than killing him, when he was the single member of the aliʻi council to agree with Kamehameha's own reluctance to do so.

The explorer George Vancouver noted that Kamehameha worshiped his gods and wooden images in a heiau, but originally wanted to bring England's religion, Christianity, to Hawaiʻi.

[40] When Kamehameha died on May 8 or 14, 1819,[41][42][43] his body was hidden by his trusted friends, Hoapili and Hoʻolulu, in the ancient custom called hūnākele (literally, "to hide in secret").

[47] In Hoʻomana: Understanding the Sacred and Spiritual, Chun stated that Keōpūolani supported Kaʻahumanu's ending of the Kapu system as the best way to ensure that Kamehameha's children and grandchildren would rule the kingdom.