Kingdom of Kandy

Though the kingdom had intermittent access to the port of Batticaloa it had no naval forces and could not prevent the Portuguese and Dutch from maintaining a strong presence in lowland areas.

Kandy territory was invaded twice in the 1570s and 1580s, first in 1574, and then in 1581 by the newly crowned king of Sithawaka Rajasinghe I. Rajasinghe – who had already scored a significant victory over the Portuguese at the Battle of Mulleriyawa – succeeded in annexing the kingdom outright; the Kandyan king Karalliyadde Kumara Bandara (also known as Jayavira III) fled north to the Jaffna Kingdom with his daughter, Kusumasana Devi (also known as Dona Catherina of Kandy) and her husband Yamasinghe Bandara.

[9] In the meanwhile the Portuguese also laid claim to the Kandyan realm, citing Dharmapala's donation of 1580 as a precedent[10] Sithawakan rule over Kandy proved difficult to enforce.

Resistance eventually coalesced around Konnappu Bandara, son of Wirasundara, who had fled to Portuguese lands following his father's murder by agents of Rajasinghe.

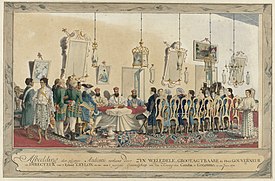

The visit ended in disaster when the visitors offended their Kandyan hosts with their behaviour and in the ensuing fracas, de Weert and several of his entourage were killed.

The throne passed to his cousin, Senarat, who at the time of the king's death was an ordained priest, but left the sangha and married Dona Catherina.

[14] The Portuguese strengthened their position throughout the 1620s, building forts at Kalutara, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and in Sabaragamuwa, and upgrading fortifications in Colombo, Galle, and Manikkadawara.

Rajasinha's hold over his own population was tenuous, and rebellions against him in 1664 and 1671 gave the Dutch the opportunity to seize large parts of Sabaragamuwa in 1665, as well as Kalpitiya, Kottiyar, Batticaloa and Trincomalee.

With the support of the bhikku Weliwita Sarankara, the crown passed to the brother of one of Narendrasinha's senior wives, a member of the Telugu-speaking and Tamil-speaking Nayak house from southern India.

As early as Narendrasinha's reign, attempts at appointing Nayakkars to prominent positions in court had caused rebellion, including one in 1732 that the king had only been able to crush with Dutch assistance.

The Nayakkar nobility – which tended to be exclusivist and monopolise access to the king – was seen as forming an elite group privileged above the native aristocracy, the powerful adigars.

The Dutch governors, subservient to Batavia, were under strict orders to avoid conflict with the kingdom, without ceding any of their privileges, including the monopoly of the cinnamon trade.

Though several British sailors and priests had landed in Sri Lanka as early as the 1590s,[27] the most famous was Robert Knox who published An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon based on his experiences during the reign of Rajasinghe II in 1681.

One hundred years later, British involvement in Sri Lankan affairs commenced in earnest with the seizure of Trincomalee by Admiral Edward Hughes as part of general British-Dutch hostilities during the American War of Independence.

Complex negotiations ensued, with various ideas – including the king being moved to British lands with Pilima Talawe acting as his viceroy in Kandy – were discussed and rejected by both sides.

The territories still possessed by the Dutch on the island were formally ceded to the British in the 1802 treaty of Amiens, but the English Company still retained a monopoly on the colony's trade.

Amidst rising tension, matters came to a head when a group of Moorish British subjects were detained and beaten by agents of Pilima Talawe's.

On 2 March 1815, British agents – including Robert Brownrigg and John D'Oyly – met with the nobility of the kingdom and concluded in a conference known as the Kandyan Convention.

[30][31][32] Brownrigg also issued a Sri Lanka Gazette Notification that condemned anyone who participated in the Great Uprising with property confiscation, extradition to Mauritius, and even execution.

(This Gazette Notification labelling the rebels as "traitors" was only revoked two centuries later, in 2017, with 81 leaders of the freedom struggle being formally declared as National Heroes.

[citation needed] The area of the central highlands in which the Kandyan kingdom was situated had the natural protection of rivers, waterways, hills and rocky mountainous terrain.

Not obeying these would be detrimental to the power of the king, an example being Vikrama Rajasinha, who had to surrender to the British, merely because he ignored the advice of the Buddhist priests and chieftains and did not follow the age old traditions.

[34] Diyawadana Nilame was an officer of the Royal household, charged with safeguarding and carrying out ancient rituals for the Sacred Relic of the tooth of the Buddha.

Kandyan forces, throughout their history, relied heavily on the mountainous terrain of the kingdom and primarily engaged in guerrilla-style hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, and quick raids.

One of the hallmarks of the clashes between the kingdom and its European foes was the inability of either side to take and hold land or to permanently cut off supply routes, with the exception being the Dutch, who managed to do so for an extended period of time in 1762.

In addition to this, various Europeans were in the King's service during this period (including a master gunner), and large contingents of Malays, who were very highly regarded as fighters.

The bulk of the Kandyan army consisted of local peasant conscripts – irregulars pressed into service in times of war – who tended to bring with them around twenty days' worth of supplies and functioned in discrete units often out of contact with each other.

One of the reasons for the Kandyan's inability to hold the land they captured was poor logistical support, as many soldiers had to return to base to replenish their supplies once they ran out.

Kandyan gunsmiths specialised in manufacturing light flintlocks known as Bondikula with smaller bores than European guns, with their barrels extended for accuracy.

The frescoes at Degaldoruva and the Ridi Vihare in Kurunegala were the notable examples of traditional Kandyan art, created by the talented monk, Devaragampola Silvaththana between 1771 and 1776.