Karelian language

Based upon toponymic and historical evidence, a form of Karelian was also spoken among the extinct Bjarmians in the 15th century.

Besides Karelian and Finnish, the Finnic subgroup also includes Estonian and some minority languages spoken around the Baltic Sea.

[19] In the Republic of Karelia, Karelian has official status as a minority language,[7] and since the late 1990s there have been moves to pass special language legislation, which would give Karelian an official status on par with Russian.

[19] Varieties can be further divided into individual dialects:[23]The Ludic language, spoken along the easternmost edge of Karelian Republic, is in the Russian research tradition counted as a third main dialect of Karelian, though Ludic shows strong relationship also to Veps, and it is today also considered a separate language.

Palatalized labials are also present in some loanwords: North Karelian b'urokratti 'bureaucrat', Livvi b'urokruattu 'bureaucrat', kip'atku 'boiling water', sv'oklu 'beet', Tver Karelian kip'atka 'boiling water', s'v'okla 'beet' (from Russian бюрократ, кипяток, свёкла).

[29] Olonets, Ludic, and Tver Karelian have the voiced affricate /dʒ/, represented in writing by the digraph ⟨dž⟩.

Example from Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Cyrillic Karelian script, transliteration and translation:[31] Cyrillic: Каи рахвас роиттахeс вäллиннÿ да тазаарвозинну омас арвос да оигeвуксис.

For example, in Kalevala, Lönnrot's orthography metsä : metsän hides the fact that the pronunciation of the original material is actually /mettšä : metšän/, with palatalization of the affricate.

For example, the native Karelian words kiza, šoma, liedžu and seičemen are kisa, soma, lietsu and seitsemän in standard Finnish.

In 1323, Karelia was divided between Sweden and Novgorod according to the Treaty of Nöteborg, which started to slowly separate descendants of the Proto-Karelian language from each other.

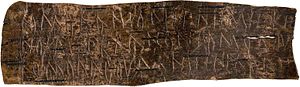

[33] It was found in 1957 by a Soviet expedition, led by Artemiy Artsikhovskiy in the Nerev excavation on the left coast side of Novgorod.

403 (second half of the 14th century), apparently belonging to a tax collector, includes a short glossary of Karelian words and their translations.

In 1617 Novgorod lost parts of Karelia to Sweden in the Treaty of Stolbovo, which led the Karelian-speaking population of the occupied areas to flee from their homes.

Karelian literature in 19th century Russia remained limited to a few primers, songbooks and leaflets.

Finnish communists as well as ethnic Finns from North America, who came to live in Soviet Karelia, dominated the political discourse, as they were in general far better educated than local Karelians.

[38] An intense program of Finnicization, but called "Karelianization", began and Finnish-language schools were established across Soviet Karelia.

[38] Between 1935 and 1938 the Finnish-dominated leadership of Soviet Karelia including leader Edvard Gylling, was removed from power, killed or sent to concentration camps.

During this period about 200 titles were published, including educational materials, children's books, readers, Party and public affairs documents, the literary journal Karelia.

Karelians who did not speak Russian could not understand this new official language due to the amount of Russian words, for example, the phrase "Which party led the revolution" in this form of Karelian was given as "Миттўйне партиуя руководи революциюа?"

Finnish, written in the Latin alphabet, was once again made the official "local" language of Soviet Karelia, alongside Russian.

A year later, Finland's first Karelian language nest (pre-school immersion group) was established in the town of Nurmes.

[39] Croatian singer Jurica Popović collaborated with Tilna Tolvaneen on lyrics for his 1999 song "H.O.T.