Kaziranga National Park

[2] According to a March 2018 census conducted jointly by the Forest Department of the Government of Assam and some recognized wildlife NGOs, the rhino population in Kaziranga National Park is 2,613.

Located on the edge of the Eastern Himalaya biodiversity hotspot, the park combines high species diversity and visibility.

In 1916, it was redesignated the "Kaziranga Game Sanctuary" and remained so till 1938, when hunting was prohibited and visitors were permitted to enter the park.

[citation needed] According to another legend, Srimanta Sankardeva, the sixteenth-century Vaisnava saint-scholar, once blessed a childless couple, Kazi and Rangai, and asked them to dig a big pond in the region so that their name would live on.

[14] Testimony to the long history of the name can be found in some records, which state that once, while the Ahom king Pratap Singha was passing by the region during the seventeenth century, he was particularly impressed by the taste of fish, and on asking was told it came from Kaziranga.

[15] Some historians believe, however, that the name Kaziranga was derived from the Karbi word Kajir-a-rong, which means "the village of Kajir" (kajiror gaon).

[19] : p.05 Kaziranga has flat expanses of fertile, alluvial soil, formed by erosion and silt deposition by the River Brahmaputra.

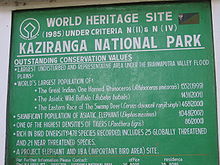

[20][21] Kaziranga is one of the largest tracts of protected land in the sub-Himalayan belt, and due to the presence of highly diverse and visible species, has been described as a "biodiversity hotspot".

[23] During the peak months of July and August, three-fourths of the western region of the park is submerged, due to the rising water level of the Brahmaputra.

During winter the shallow beels and nullahs (small water channel) dry up and the growth of short grasses cover up their beds.

With few winter showers fresh grass blades shoot up in the burnt patches attracting larger number of animals to these areas.

[26] With the onset of the summer season the grasses in the burnt patches grow up quickly and the tender shoots turn into coarse blades, which no longer attract the animals.

[citation needed] The park has the distinction of being home to the world's largest population of the Indian rhinoceros (2,401),[28][29] wild water buffalo (1,666)[30] and eastern swamp deer (468).

[34] The Indian rhinoceros, royal Bengal tiger, Asian elephant, wild water buffalo and swamp deer are collectively known as 'Big Five' of Kaziranga.

Kaziranga is one of the few wild breeding areas outside Africa for multiple species of large cats, such as Bengal tigers and Indian leopard.

[citation needed] Annual flooding, grazing by herbivores, and controlled burning maintain and fertilize the grasslands and reeds.

Amidst the grasses, providing cover and shade are scattered trees—dominant species including kumbhi, Indian gooseberry, the cotton tree (in savanna woodlands), and elephant apple (in inundated grasslands).

[citation needed] Thick evergreen forests, near the Kanchanjhuri, Panbari, and Tamulipathar blocks, contain trees such as Aphanamixis polystachya, Talauma hodgsonii, Dillenia indica, Garcinia tinctoria, Ficus rumphii, Cinnamomum bejolghota, and species of Syzygium.

Common trees and shrubs are Albizia procera, Duabanga grandiflora, Lagerstroemia speciosa, Crateva unilocularis, Sterculia urens, Grewia serrulata, Mallotus philippensis, Bridelia retusa, Aphania rubra, Leea indica, Terminalia tomentosa, Cinnamomum cassia, Durio zibethinus, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Ficus benghalensis, Gnetum gnemon, Mangifera indica, Toona ciliata, Toona sinensis, Cocos nucifera, Ginkgo biloba, Prunus serrulata, Camphora officinarum, Cathaya argyrophylla, Taiwania cryptomerioides, Cyathea spinulosa, Sassafras tzumu, Davidia involucrata, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, Glyptostrobus pensilis, Castanea mollissima, Quercus myrsinifolia, Quercus acuta, Quercus glauca, Machilus thunbergii, Tetracentron, Tsuga dumosa, Ulmus lanceifolia, Tectona grandis, Larix gmelinii, Larix sibirica, Larix × czekanowskii, Betula dahurica, Betula pendula, Pinus koraiensis, Pinus sibirica, Pinus sylvestris, Picea obovata, Abies sibirica, Quercus acutissima, Quercus mongolica, Prunus padus, Tilia amurensis, Salix babylonica, Acer palmatum, Acer campbellii, Populus tremula, Ulmus davidiana, Ulmus pumila, Pinus pumila, Haloxylon ammodendron, Elaeagnus angustifolia, Tamarix ramosissima, Pinus roxburghii, Pinus hwangshanensis, Juniperus tibetica, Olea europaea subsp.

[44] Another invasive species, Mimosa invisa, which is toxic to herbivores, was cleared by Kaziranga staff with help from the Wildlife Trust of India in 2005.

Various laws, which range in dates from the Assam Forest Regulation of 1891 and the Biodiversity Conservation Act of 2002 have been enacted for protection of wildlife in the park.

Preventive measures such as construction of anti-poaching camps and maintenance of existing ones, patrolling, intelligence gathering, and control over the use of firearms around the park have reduced the number of casualties.

[18] To escape the water-logged areas, many animals migrate to elevated regions outside the park boundaries where they are susceptible to hunting, hit by speeding vehicles, or subject to reprisals by villagers for damaging their crops.

[citation needed] Several corridors have been set up for the safe passage of animals across National Highway–37 which skirts around the southern boundary of the park.

[54] To prevent the spread of diseases and to maintain the genetic distinctness of the wild species, systematic steps such as immunization of livestock in surrounding villages and fencing of sensitive areas of the park, which are susceptible to encroachment by local cattle, are undertaken periodically.

[18]: p.19 Increase in tourist inflow has led to the economic empowerment of the people living at the fringes of the park, by means of tourism related activities, encouraging a recognition of the value of its protection.

[56] Recently set up Kaziranga National Orchid and Biodiversity Park established at Durgapur village is a latest attraction to the tourists.

The park first gained international prominence after Robin Banerjee, a physician-turned-photographer and filmmaker, produced a documentary titled Kaziranga, which was aired on television in Berlin in 1961 and became a runaway success.

[59][60][61] American science fiction and fantasy author, L. Sprague de Camp wrote about the park in his poem, "Kaziranga, Assam".

It was first published in 1970 in Demons and Dinosaurs, a poetry collection, and was reprinted as Kaziranga in Years in the Making: the Time-Travel Stories of L. Sprague de Camp in 2005.