Kechewaishke

– September 7, 1855) was a major Ojibwa leader, born at La Pointe in Lake Superior's Apostle Islands, in what is now northern Wisconsin, USA.

Recognized as the principal chief of the Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwa)[1] for nearly a half-century until his death in 1855, he led his nation into a treaty relationship with the United States Government.

He was instrumental in resisting the United States' efforts to remove the Ojibwa to western areas and secured permanent Indian reservations for his people near Lake Superior in what is now Wisconsin.

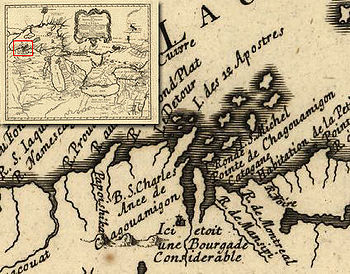

Now part of Wisconsin, La Pointe was a key Ojibwa village and trading center for the empire of New France, which was fighting the Seven Years' War against Great Britain at the time of Kechewaishke's birth.

These bands in the western Lake Superior and Mississippi River regions regarded La Pointe as their "ancient capital" and spiritual center.

At the time of first French contact in the mid-17th century, men of the Crane doodem held the positions of hereditary peace chiefs of Ojibwa communities at both Sault Ste.

When Tecumseh's War broke out, Kechewaishke and a number of other young warriors from the La Pointe area abandoned the Midewiwin for a time to follow the teachings of the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa.

While en route to Prophetstown to join the attack on the Americans, they were stopped by Michel Cadotte, the respected Métis fur trader from La Pointe.

He also drew a contrast between himself and his contemporaries Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay and Hole in the Day, two Ojibwa chiefs from present-day Minnesota, who carried out a long war against the Dakota Sioux people.

[15] Although Armstrong records Kechewaishke winning a large victory over the Dakota in the 1842 Battle of the Brule, 20th-century historians have cast doubt on his account.

Noted for his abilities in hunting and battle, he was recognized as chief by his people because of his speaking and oratorical skills, which were highly valued in his culture.

In 1825, Kechewaishke was one of 41 Ojibwa leaders to sign the First Treaty of Prairie du Chien, with his name recorded as "Gitspee Waishkee" or La Boeuf.

[19] Shortly after the treaties were signed, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, acting in his capacity as US Indian agent, visited La Pointe.

Historians take this to mean that while he was regarded as the head spokesman of the Ojibwa in Wisconsin, he could not control the day-to-day affairs of all the bands, which were highly decentralized, particularly with respect to warfare.

[20] In the next decades, there was pressure from Americans who wanted to exploit the mineral and timber resources of Ojibwa country, and the US government sought to acquire control of the territory through treaties.

Despite the impatience of the territorial governor, Henry Dodge, the negotiations were delayed for five days as the assembled bands waited for Kechewaishke to arrive.

Acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs Henry Stuart, who was promoting development of the Lake Superior copper industry, led the negotiations for the US government.

The Ojibwa did obtain annuity payments to be paid each year at La Pointe, and reserved the right to hunt, fish, gather, and move across any lands outlined in the treaties.

But President Zachary Taylor signed the removal order on February 6, 1850, under corrupt circumstances, claiming to be protecting the Ojibwa from "injurious" whites.

[29] To force the Ojibwa to comply, Watrous announced he would pay future annuities only at Sandy Lake, Minnesota, instead of La Pointe, where they had been paid previously.

This change resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy, when hundreds of Ojibwa starved or died of exposure in Minnesota and on the journey home because the promised annuity supplies were late, contaminated or inadequate.

Kechewaishke called on the services of his well-spoken sub-chief Oshoga, and son-in-law Benjamin G. Armstrong, a literate white interpreter married to his daughter.

Along the way, they stopped in towns and mining camps along the Michigan shore of Lake Superior, securing hundreds of signatures in support of their cause.

The next day, he announced that the removal order would be canceled, the payment of annuities would be returned to La Pointe, and another treaty would set up permanent reservations for the Ojibwa in Wisconsin.

Ambiguity in those treaties had been partially to blame for ensuing problems, so Kechewaishke insisted he would accept no interpreter other than Armstrong, his adopted son.

The Ojibwa insisted on a guarantee of the right to hunt, fish, and gather on all the ceded territory, and on the establishment on several reservations across western Upper Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and northeastern Minnesota.

[35] A small tract of land was also set aside for Kechewaishke and his family at Buffalo Bay on the mainland across from Madeline Island at a place called Miskwaabikong (red rocks or cliffs).

Kechewaishke was described as "head and the chief of the Chippewa Nation" and a man respected "for his rare integrity, wisdom in council, power as an orator, and magnanimity as a warrior."

He is buried in the La Pointe Indian Cemetery, near the deep, cold waters of Ojibwe Gichigami (Lake Superior), the "great freshwater-sea of the Ojibwa."

Beginning in 1983, during treaty conflicts known as the Wisconsin Walleye War, Kechewaishke's name was frequently invoked as one who refused to give up his homeland and tribal sovereignty.