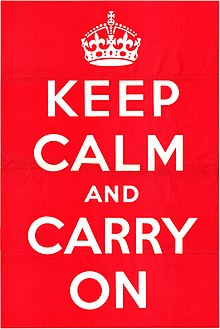

Keep Calm and Carry On

The poster was intended to raise the morale of the British public, threatened with widely predicted mass air attacks on major cities.

[4] Evocative of the Victorian belief in British stoicism – the "stiff upper lip", self-discipline, fortitude, and remaining calm in adversity – the poster has become recognised around the world.

[5] It was thought that only two original copies survived until a collection of approximately 15 was brought in to the Antiques Roadshow in 2012 by the daughter of an ex-Royal Observer Corps member.

Keep Calm was intended to be distributed to strengthen morale in the event of a wartime disaster, such as mass bombing of major cities using high explosives and poison gas, which was widely expected within hours of an outbreak of war.

[2][10] Others involved in the planning of the early posters included: John Hilton, Professor of Industrial Relations at Cambridge University, responsible overall as Director of Home Publicity; William Surrey Dane, managing director at Odhams Press; Gervas Huxley, former head of publicity for the Empire Marketing Board; William Codling, controller of HMSO; Harold Nicolson, MP; W. G. V. Vaughan, who became Director of the General Production Division (GPD); H. V. Rhodes, who later wrote an occasional paper on setting up a new government department; Ivison Macadam; "Mr Cruthley"; and "Mr Francis".

[9] Roughs of the poster were completed on 6 July 1939, and the final designs were agreed by the Home Secretary Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood on 4 August 1939.

Printing began on 23 August 1939, the day that Nazi Germany and the USSR signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and the posters were ready to be placed up within 24 hours of the outbreak of war.

[3] An example also features in a drawing of a London Underground station by Floyd MacMillan Davis, published in Life magazine in 1944, suggesting a more widespread distribution.

[20] The posters had been conceived on the assumption that enemy attacks of the civilian population would begin as soon as war was declared, and that there would be a great need for "a copious issue of general reassurance material".

[21][22] Design historian Susannah Walker regards the campaign as "a resounding failure" and reflective of a misjudgement by upper-class civil servants of the mood of the people.

[23] Stuart Manley suggests that the negative reaction to the first two posters resulted in Keep Calm being held back, and that this was an error of judgement: "If they had started with this one, I think it would have been just as popular then as it is now.

[3] In late May and early June 1941, 14,000,000 copies of a leaflet entitled "Beating the Invader" were distributed with a message from Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

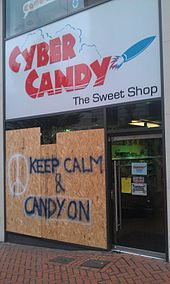

"[28] In early 2012, Barter Books debuted an informational short film, The Story of Keep Calm and Carry On, providing visual insight into the modernisation and commercialisation of the design and the phrase.

The company's right to claim the trademark was questioned by, among others, the Manleys of Barter Books, as the slogan had been widely used before registration and was not recognisable as indicating trade origin.