Ned Kelly

Kelly continues to cause division in his homeland: he is variously considered a Robin Hood-like folk hero and crusader against oppression, and a murderous villain and terrorist.

[5] Aged 21, he was found guilty of stealing two pigs[6] and was transported on the convict ship Prince Regent to Hobart Town, Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania), arriving on 2 January 1842.

[5] On 18 November 1850, at St Francis Church, Melbourne, Red married Ellen Quinn, his employer's 18-year-old daughter, who was born in County Antrim, Ireland and migrated as a child with her parents to the Port Phillip District.

[11] His parents had seven other children: Mary Jane (born 1851, died 6 months later), Annie (1853–1872), Margaret (1857–1896), James ("Jim", 1859–1946), Daniel ("Dan", 1861–1880), Catherine ("Kate", 1863–1898) and Grace (1865–1940).

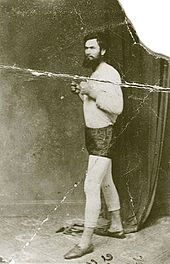

[18] I'm a bushranger.In 1869, 14-year-old Kelly met Irish-born Harry Power (alias of Henry Johnson), a transported convict who turned to bushranging in north-eastern Victoria after escaping Melbourne's Pentridge Prison.

A Chinese hawker named Ah Fook said that as he passed the Kelly family home, Ned brandished a long stick, declared himself a bushranger and robbed him of 10 shillings.

[44] Many years later, Kelly's brother Jim and cousin Tom Lloyd claimed that Fitzpatrick was drunk when he arrived at the house, and while seated, pulled Kate onto his knee, provoking Dan to throw him to the floor.

In the ensuing struggle, Fitzpatrick drew his revolver, Ned appeared, and with Dan seized and disarmed the constable, who later claimed a wrist injury from a door lock was a gunshot wound.

In a letter to Acting Chief Secretary Bryan O’Loghlen, Kelly accused the government of "committing a manifest injustice in imprisoning so many innocent people" and threatened reprisals.

[86] At 10 am on 10 February, Ned and Byrne donned police uniforms and took Richards with them into town, leaving Devine in the lockup and warning his wife that they would kill her and her children if she left the barracks.

[87] The gang held up the Royal Mail Hotel and, while Dan and Hart controlled the hostages, Ned and Byrne robbed the neighbouring Bank of New South Wales of £2,141 in cash and valuables.

[92] I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future.Prior to arriving in Jerilderie, Kelly composed a lengthy letter with the aim of tracing his path to outlawry, justifying his actions, and outlining the alleged injustices he and his family suffered at the hands of the police.

He also implores squatters to share their wealth with the rural poor, invokes a history of Irish rebellion against the English, and threatens to carry out a "colonial stratagem" designed to shock not only Victoria and its police "but also the whole British army".

[97] It has been interpreted as a proto-republican manifesto;[98] one eyewitness to the Jerilderie raid noted that the letter suggested Kelly would "have liked to have been at the head of a hundred followers or so to upset the existing government".

[104]In response to the Jerilderie raid, the New South Wales government and several banks collectively issued £4,000 for the gang's capture, dead or alive, the largest reward offered in the colony since £5,000 was placed on the heads of the outlawed Clarke brothers in 1867.

[112] Facing media and parliamentary criticism over the costly and failed gang search, Standish appointed Assistant Commissioner Charles Hope Nicolson as leader of operations at Benalla on 3 July 1879.

[119][120] In the following months, Byrne and Ned sent invitations to Sherritt to join the gang, but when he continued his relationship with the police, the outlaws decided to murder him as a means to launch a grander plot, one that they boasted would "astonish not only the Australian colonies but the whole world".

[149] Eyewitnesses struggled to identify the figure moving in the dim misty light and, astonished as it withstood bullets, variously called it a ghost, a bunyip, and the devil.

It was the most extraordinary sight I ever saw or read of in my life, and I felt fairly spellbound with wonder, and I could not stir or speak.The gun battle with Kelly lasted around 15 minutes with Dan and Hart providing covering fire from the hotel.

[158] Passing through the area, Catholic priest Matthew Gibney halted his travels to administer the last rites to Ned, then entered the burning hotel in an attempt to rescue anyone inside.

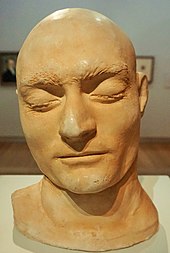

[210] On 20 January 2013, following a Requiem Mass at St Patrick's Catholic Church, Wangaratta, Kelly's final wish was granted as his remains were buried in consecrated ground at Greta Cemetery, near his mother's unmarked grave.

[213]Seal argues that Kelly's story taps into the Robin Hood tradition of the outlaw hero and the myth of the Australian bush as a place of freedom from oppressive authority.

Reviewing an 1881 performance of the Kelly gang play Ostracised, staged at Melbourne's Princess Theatre, The Australasian wrote:[215] ... judging from the way in which the applause was dealt out, it was pretty certain that the exploits of the outlaws excited admiration and prompted emulation.

[221]The siege at Glenrowan became a national and international media event, and reports of the armour sparked widespread fascination, cementing Kelly and his gang's lasting infamy.

[220] Expanding on this thesis, McQuilton argues that the Kelly outbreak should be seen in the context of increased poverty in north-eastern Victoria in the 1870s and a conflict over land between selectors (mostly small-scale farmers) and squatters (mostly wealthier pastoralists with more political influence).

[245] As for the alleged republican declaration or plan for a political rebellion, Dawson writes that no such document or intention appears in any records, interviews, memoirs or accounts from those connected to the gang or early historians.

[247] While Kelly often complained of oppression by the police and squatters, rejected the legitimacy of the Victorian government and British monarchy, and evoked Irish nationalist grievances against what he called "the tyrannism of the English yoke", his response manifested as a violent reckoning rather than a clear political program.

[248][249][95] Seal states that in the Jerilderie Letter, Kelly advocates "a rebalancing of the social and economic system of the region": squatter profits will be redistributed to the poor, who, in turn, will form a community guard, rendering the police unnecessary.

[250][251][252] Morrissey, however, sees the social justice element of the letter as a traditional call for the rich to help the poor, and argues that Kelly's vision for society is driven by personal vengeance and a desire to consolidate his power through violence and terror.

[253] Communist activist Ted Hill states that in the decades after Kelly's execution, his legacy became linked with a "democratic rebellious spirit" that influenced both the working class and leftist intellectuals.