Kharijites

Modern, academic historians are generally divided in attributing the Kharijite phenomenon to purely religious motivations, economic factors, or a Bedouin (nomadic Arab) challenge to the establishment of an organized state, with some rejecting the traditional account of the movement having started at Siffin.

Toward this purpose, stories are sometimes created, or real events altered, in order to romanticize and valorize early Kharijite revolts and their leaders as the anchors of the group identity.

[g] The early Muslim settlers of the garrison towns of Kufa and Fustat, in the conquered regions of Iraq and Egypt, felt their status threatened by several factors during this period.

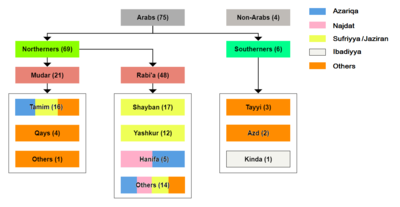

[32][36][i] While most of Ali's army accepted the agreement, one group, which included many Tamim tribesmen, vehemently objected to the arbitration and raised the slogan 'judgment belongs to God alone' (la hukma illa li-llah).

[52] After the Kharijites refused to surrender the murderers, Ali's men attacked their camp, inflicting a heavy defeat on them at the Battle of Nahrawan (July 658), in which al-Rasibi and most of his supporters were slain.

Under the leadership of Farwa ibn Nawfal al-Ashja'i of the Banu Murra, some 500 of them attacked Mu'awiya's camp at Nukhayla (a place outside Kufa) where he was taking the Kufans' oath of allegiance.

[59][60] There, he confronted the deputy governor Simak ibn Ubayd al-Absi and invited him to denounce Uthman and Ali "who had made innovations in the religion and denied the holy book".

His followers are called Azariqa after their leader, and are described in the sources as the most fanatic of the Kharijite groups, for they approved the doctrine of isti'rad: indiscriminate killing of the non-Kharijite Muslims, including their women and children.

In late 686, Muhallab discontinued his campaign as he was sent to rein in the pro-Alid ruler of Kufa, Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, and was afterward appointed governor of Mosul to defend against possible Umayyad attacks from Syria.

[91] Ibadi sources too are more or less in line with this scheme, where the Ibadiyya appear as the true successors of the original Medinese community and the early, pre-Second-Fitna Kharijites, though Ibn Ibad does not feature prominently and Jabir is asserted as the leader of the movement following Abu Bilal Mirdas.

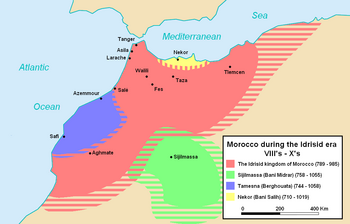

During the final years of the Umayyad Caliphate, the Ibadi propaganda movement caused several revolts in the periphery of the empire, though the leaders in Basra adopted the policy of kitman (also called taqiyya); concealing beliefs so as to avoid persecution.

[118][m] In addition to their insistence on rule according to the Qur'an,[119] the view common to all Kharijite groups was that any Muslim was qualified to become caliph, regardless of origin, if he had the credentials of belief and piety.

[118] Uthman, on the other hand, had deviated from the path of justice and truth in the latter half of his caliphate and was thus liable to be killed or deposed, whereas Ali committed a grave sin when he agreed to the arbitration with Mu'awiya.

[122] If the leader committed a sin and deviated from the right path or failed to manage Muslims' affairs through justice and consultation, he was obliged to acknowledge his mistake and repent, or else he forfeited his right to rule and was subject to deposition.

[120] The Azariqa and Najdat held that since the Umayyad rulers, and all non-Kharijites in general, were unbelievers, it was unlawful to continue living under their rule (dar al-kufr), for that was in itself an act of unbelief.

[6] The Islamicist Montgomery Watt attributes this moderation of the Najdat stance to practical necessities which they encountered while governing Arabia, as the administration of a large area required flexibility and allowance for human imperfection.

[145] Many Kharijites were well-versed in traditional Arabic eloquence and poetry, which the orientalist Giorgio Levi Della Vida attributes to the majority of their early leaders being from Bedouin stock.

[150] Imran ibn Hittan, whom the Arabist Michael Cooperson calls the greatest Kharijite poet,[151] sang after Abu Bilal's death: "Abū Bilāl has increased my disdain for this life; and strengthened my love for the khurūj [rebellion]".

[152] The poet Abu'l-Wazi al-Rasibi addressed Ibn al-Azraq, before the latter became activist, with the lines:[150] Your tongue does no harm to the enemy you will only gain salvation from distress by means of your two hands.

[172] Their religious worldview was based on Qur'anic values, and they may have been the "real true believers" and "authentic representatives of the earliest community" of Muslims, instead of a divergent sect as presented by the sources.

[149] Their militancy may have been caused by the expectation of the imminent end of the world, for the level of violence in their revolts and their extreme longing for martyrdom cannot be explained solely on the basis of belief in the afterlife.

They supported the arbitration because they assumed it would bring an end to the war, with Ali retaining the caliphate and returning to Medina, leaving the administration of Iraq in the hands of the local population, including themselves.

[186] The Islamicist Chase F. Robinson describes the Jaziran Kharijites as disgruntled army commanders with tribal followings, who adopted Kharijism to provide a religious cover to their banditry.

The quietists' more nuanced and practical approach, in which they preferred taqiyya over hijra, engaged in organized and sustainable military campaigns and institution-building, as opposed to aggressive pursuit of martyrdom, all contributed to their survival.

[21] Wellhausen has argued that Kharijite dogmatism influenced the development of the mainstream Muslim theology, in particular their debates in relation to faith and deeds, and legitimate leadership.

[192] In the view of Watt, the Kharijite insistence on the rule according to the Qur'an prevented the early Muslim empire from turning into a purely secular Arab state.

[194] In order to make clearer the distinction between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, the mainstream sources attempted to portray the Kharijites as a monolithic, identifiable group, with the characteristics and practices of the most radical sect, the Azariqa, being presented as representative of the whole.

[195] The term Khawarij, which originally meant those who went out of Kufa to gather at Nahrawan during the time of Ali, was subsequently understood as 'outsiders'—those who went out of the fold of the Muslim community—rebels, and brutal extremists.

[203] In particular, the groups are alleged to share the militant Kharijites' anarchist and radical approach, whereby self-described Muslims are declared unbelievers and therefore deemed worthy of death.

They compare the Kharijite ideals of ethnic and gender equality with the modern equivalents of these values and consider them representatives of proto-democratic thought in early Islam.