Criticism of Muhammad

[8][9][10] During the Middle Ages, various[3][5][6][11] Western and Byzantine Christian thinkers considered Muhammad to be a deplorable man,[3] a false prophet,[3][4][5][6] and even the Antichrist,[3][5] as he was frequently seen in Christendom as a heretic[2][3][4][5] or possessed by demons.

In the Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati, a dialogue between a recent Christian convert and several Jews, one participant writes that his brother "wrote to [him] saying that a deceiving prophet has appeared amidst the Saracens".

These references played a principal role in introducing Muhammad and his religion to the West as the false prophet, Saracen prince or deity, the Biblical beast, a schismatic from Christianity and a satanic creature, and the Antichrist.

[26] Many early former Muslims such as Ibn al-Rawandi, Al-Ma'arri, and Abu Isa al-Warraq were religious skeptics, and philosophers who criticized Islam,[11] the authority and reliability of the Qu'ran,[11] Muhammad's morality,[11] and his claims to be a prophet.

[24] During the 13th century a series of works by European scholars such as Pedro Pascual, Ricoldo de Monte Croce, and Ramon Llull[24] depicted Muhammad as an Antichrist and argued that Islam was a Christian heresy.

In describing the travels of Joseph of Arimathea, keeper of the Holy Grail, the author says that most residents of the Middle East were pagans until the coming of Muhammad, who is shown as a true prophet sent by God to bring Christianity to the region.

[31] The Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii, an Andalusian manuscript with unknown dating, recounts how Muhammad (called Ozim, from Hashim) was tricked by Satan into adulterating an originally pure divine revelation.

[32] In Summa Contra Gentiles Thomas Aquinas wrote a critical view of Muhammad, suggesting that his teachings aligned closely with worldly desires and lacked strong support from earlier religious texts.

"[37][38] In a 1740 letter to Frederick II of Prussia, Voltaire criticized Muhammad's actions, attributing his influence to superstition and a lack of Enlightenment values,[39] and described him as "a Tartuffe with a sword in his hand.

[42] Voltaire also referred to Muhammad as a "poet" and recognized him as a literate figure and drew parallels between Arabs and ancient Hebrews, noting their shared fervor for battle in the name of God.

[45] As a result, his book Fanaticism (Mohammad the Prophet), inspired Goethe, who was attracted to Islam, to write a drama on this theme, though completed only the poem Mahomets-Gesang ("Mahomet's Singing").

Margoliouth "give us a more correct and unbiased estimate of Muhammad's life and character, and substantially agree as to his motives, prophetic call, personal qualifications, and sincerity.

"[30] Samuel Marinus Zwemer, a Christian missionary, criticised the life of Muhammad by the standards of the Old and New Testaments, by the pagan morality of his Arab compatriots, and last, by the new law which he brought.

[48] Quoting Johnstone, Zwemer concludes by claiming that his harsh judgment rests on evidence which "comes all from the lips and the pens of his [i.e. Muhammad's] own devoted adherents.

[59][60][61] According to sociologist Rodney Stark, "the fundamental problem facing Muslim theologians vis-à-vis the morality of slavery" is that Muhammad himself engaged in activities such as purchasing, selling, and owning slaves, and that his followers saw him as the perfect example to emulate.

[72][Note 1] Jean de Sismondi suggests that Muhammad's successive attacks on powerful Jewish colonies located near Medina in Arabia were due to religious differences between them, and he claimed that he subjected the defeated to punishments that were not typical in other wars.

[75][76][77][78] After the Qurayẓah were found to be complicit with the enemy during the Battle of the Ditch, the Muslim general Sa'd ibn Mu'adh ordered the men to be put to death and the women and children to be enslaved.

[79] Regardless, "this tragic episode cast a shadow upon the relations between the two communities for many centuries, even though the Jews, a "People of the Book" [...] generally enjoyed the protection of their lives, property, and religion under Islamic rule and fared better in the Muslim world than in the West.

[97] John Esposito states that polygamy served multiple purposes, including solidifying political alliances among Arab chiefs and marrying widows of companions who died in combat that needed protection.

And Allah's command must be fulfilled.Following the revelation of this verse, Muhammad rejected the prevailing Arab customs that prohibited marrying the wives of adopted sons, which was considered taboo and culturally inappropriate.

[147] The Christian minister Archdeacon Humphrey Prideaux gave the following description of Muhammad's visions:[147] He pretended to receive all his revelations from the Angel Gabriel, and that he was sent from God of purpose to deliver them unto him.

And whereas he was subject to the falling-sickness, whenever the fit was upon him, he pretended it to be a Trance, and that the Angel Gabriel comes from God with some Revelations unto him.Some modern Western scholars also have a skeptical view of Muhammad's seizures.

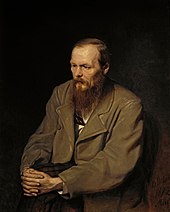

Dostoyevsky claimed that his own attacks were similar to those of Muhammad: "Probably it was of such an instant, that the epileptic Mahomet was speaking when he said that he had visited all the dwelling places of Allah within a shorter time than it took for his pitcher full of water to empty itself.

"[147] In an essay that discusses views of Muhammad's psychology, Franz Bul (1903) is said to have observed that "hysterical natures find unusual difficulty and often complete inability to distinguish the false from the true", and to have thought this to be "the safest way to interpret the strange inconsistencies in the life of the Prophet."

[153] Fazlur Rahman refutes epileptic fits for the following reasons: Muhammad's condition begins with his career at the age of 40; according to the tradition seizures are invariably associated with the revelation and never occur by itself.

Watt concludes by stating "It is incredible that a person subject to epilepsy, or hysteria, or even ungovernable fits of emotion, could have been the active leader of military expeditions, or the cool far-seeing guide of a city-state and a growing religious community; but all this we know Muhammad to have been.

[79] By stating that Muslims should perpetually be ruled by a member of his own Quraysh tribe after him, Muhammed is accused of creating an Islamic aristocracy, contrary to the religion's ostensibly egalitarian principles.

[166] In this reckoning, he introduced a hereditary elite topped by his own family and descendants (the Ahlul Bayt and sayyids), followed by his clan (Banu Hashim) then tribe (Quraysh).

He asserts that "in the Meccan period of [Muhammad's] life there certainly can be traced no personal ends or unworthy motives," painting him as a man of good faith and a genuine reformer.

When they justified themselves by referring to the Bible, Muhammad, who had taken nothing therefrom at first hand, accused them of intentionally concealing its true meaning or of entirely misunderstanding it, and taunted them with being "asses who carry books" (sura lxii.