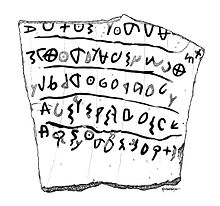

Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon

[5] The editio princeps of the inscription was published by Haggai Misgav, Yosef Garfinkel, and Saar Ganor in the 2009 Khirbet Qeiyafa excavation volume.

[2] They proposed the following reading of the ostracon: While they did not offer a translation, they did suggest on the basis of a few extant lexemes that the inscription was the earliest example of Hebrew writing.

[8] On January 10, 2010, the University of Haifa issued a controversial press release claiming decipherment of the text and that it contained a social statement relating to slaves, widows and orphans.

According to this interpretation, the text "uses verbs that were characteristic of Hebrew, such as ‘śh (עשה) ("did") and ‘bd (עבד) ("worked"), which were rarely used in other regional languages.

It was further maintained that the present inscription yielded social elements similar to those found in the biblical prophecies, markedly different from those current in other cultures, which write of the glorification of the gods and taking care of their physical needs.

A 2011 article by Christopher Rollston presents his reflections on the inscription, including comments pertaining to its script and the possibility of identifying the language.