Khomeinism

Traditional Twelver theologians urged believers to wait patiently for his return, but Khomeini and his followers called upon Shia Muslims to actively pave the way for Mahdi's global Islamic rule.

In modern times the Grand Ayatollah Mirza Shirazi intervened against Nasir al-Din Shah when in 1890 that Qajar monarch gave a 50-year monopoly over the distribution and exportation of tobacco to a foreign non-Muslim.

In 1970, Khomeini broke from this tradition, developing a fourth approach to the state, a revolutionary change in Shia Islam proclaiming that monarchy was inherently unjust, and that religious legal scholars should not just become involved in politics but rule.

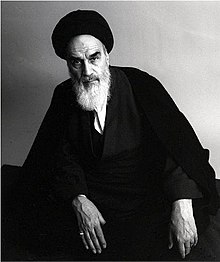

thesis by Mohammad Rezaie Yazdi (Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism), where Yazdi "attempts to show how the Ayatullah" emphasized a clash between the United States and "Iranian national freedom and religious pride"[16] Principlist groups Monarchist groups Monarchists Defunct At least one scholar (Ervand Abrahamian) has argued that Khomeini's "decrees, sermons, interviews, and political pronouncements" have outlasted his theological works because it is the former and not the latter that the Islamic Republic of Iran "constantly reprints."

[32] Khomeini's insistence on a religious state governed by select members of Shia clergy was closely linked to his reformulation of Twelver Shi'ite messianic beliefs on Mahdism.

Since the emergence of the 2009 Green movement, a "cult of Mahdism" has been heavily promoted by the IRGC and state-backed clergy in an attempt to deter the youth from embracing secular ideas; and it is strongly tied to the inner circle of Ali Khamenei.

In the contemporary world, Khomeini held Western colonial conspiracies responsible for keeping the country poor and backward, exploiting its resources, inflamed class antagonism, dividing the clergy and alienating them from the masses, causing mischief among the tribes, infiltrating the universities, cultivating consumer instincts, and encouraging moral corruption, especially gambling, prostitution, drug addiction, and alcohol consumption.

They preached "a return to `native roots` and eradication of `cosmopolitan ideas.`[45] It claimed "a noncapitalist, noncommunist `third way` towards development," [45] but was intellectually "flexible",[46] emphasizing "cultural, national, and political reconstruction," not economic and social revolution.

[52] but after he had returned to Iran and the Shah's government had collapsed, told a huge crowd of Iranians, "Do not use this term, `democratic.` That is the Western style,`" [53] One explanation for this change of position is that Khomeini needed the support of the pro-democracy educated middle class to take power.

Abrahamian argues Khomeini wanted to "forge unity" among "his disparate followers, [and] raise formidable – if not insurmountable – obstacles in the way of any future leader hoping to initiate a detente with the West," and most importantly to "weed out the half-hearted from the true believers",[69] such as heir-designate Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri, who protested the killings and was dismissed from his position.

"[74] His lack of attention has been described as "possibly one factor explaining the inchoate performance of the Iranian economy since the 1979 revolution," (along with the mismanagement by clerics trained in Islamic law but not economic science).

[79] In his last will and testament, he urged future generations to respect property on the grounds that free enterprise turns the `wheels of the economy` and prosperity would produce `social justice` for all, including the poor.

[80][81] What one scholar (Ervand Abrahamian) called the populist thrust of Khomeini can be found in the fact that after the revolution, revolutionary tribunals expropriated "agribusinesses, large factories, and luxury homes belonging to the former elite," but were careful to avoid "challenging the concept of private property.

"[85] In October 1962 when the shah introduced a plan to (among other things) let women vote for the first time, Khomeini (and other religious people) were enraged: `The son of Reza Khan has embarked on the destruction of Islam in Iran.

Hamid Dabashi argues Khomeini's theory of Esmat from faith helped "to secure the all-important attribute of infallibility for himself as a member of the awlia' [friend of God] by eliminating the simultaneous theological and Imamological problems of violating the immanent expectation of the Mahdi.

Writing in 2006, Vali Nasr states that "until fairly recently" willingness to die for the cause" (with suicide bombing or other means) was seen as a "predominantly Shia phenomenon, tied to the myths of Karbala and the Twelfth Imam",[101] though it has since spread to Sunni Islam.

This world, despite all its apparent splendor and charm, is too worthless to be loved[105]Khomeini never wavered from his faith in the war as God's will, and observers have related a number of examples of his impatience with those who tried to convince him to stop it.

"[106] On another occasion Khomeini showed his disdain for a delegation of Muslim heads of state who had come to Tehran to offer to mediate an end to the war by keeping them waiting for two hours, and speaking to them for only ten minutes without providing a translator before getting up and leaving.

"[135] His image was as "absolute, wise, and indispensable leader of the nation":[136] The Imam, it was generally believed, had shown by his uncanny sweep to power, that he knew how to act in ways which others could not begin to understand.

The following was published in 1942 and republished during his years as supreme leader: Jihad or Holy War, which is for the conquest of countries and kingdoms, becomes incumbent after the formation of the Islamic state in the presence of the Imam or in accordance with his command.

[175] Khomeini made efforts to establish unity among Ummah and "bridge the gap between Shiites and Sunnis", especially during the early days of the Revolution,[176] according to at least Vali Nasr because "he wanted to be accepted as the leader of the Muslim world, period".

In our domestic and foreign policy, ... we have set as our goal the world-wide spread of the influence of Islam ... We wish to cause the corrupt roots of Zionism, capitalism and Communism to wither throughout the world.

We wish, as does God almighty, to destroy the systems which are based on these three foundations, and to promote the Islamic order of the Prophet ...[191][167][168][169]Despite commonalities between the Islamic Republic and Marist thought and practice – Iran nationalized many of its industries, strongly denounced foreign intervention of capitalist powers, shared anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist rhetoric (even borrowing imagery from Marxists),[192][note 4] while Iran's Tudeh (Communist) party saw itself as part of "a front of cooperation ... for popular support of the anti-imperialist revolution of February 1979"before its membership was imprisoned – Khomeini was "anti-Marxist",[194] and did not follow the Marxist economic analysis of capitalism being the cause of imperialism, and socialism its cure.

Even before taking power, Khomeini attacked the Iranian left, claiming that the Tudeh party was cooperating with the shah, accusing Marxists of planning "to stab Muslims in the back, and denounced Russia as a greedy superpower".

[217]He led direct action against his opponents, such as an around-the-clock sit-in for three months by a large group of followers in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine; recruiting mercenaries to harass the supporters of democracy, and leading a mob towards Tupkhanih Square December 22, 1907 to attack merchants and loot stores.

[220] Khomeini's manifesto Islamic Government, Guardianship of the jurist, was (according to Mehdi Khalaji) greatly influenced by Rida's book and by his analysis of the post-colonial Muslim world.

[223] According to Encyclopaedia Iranica, "there are important similarities between much of the Fedāʾīān's basic views and certain principles and actions of the Islamic Republic of Iran: the Fedāʾīān and Ayatollah Khomeini were in accord on issues such as the role of clerics", (who should be judges, educators and moral guides to the people); of ethics and morality, (where all non-Islamic laws should be abolished and all sharia law applied, thus limiting all sorts of behavior); the place of the poor (to be raised up), the rights of religious minorities and women, (to be kept down), and "attitudes toward foreign powers" (dangerous conspirators to be kept out).

[238] Fighting Gharbzadegi became part of the ideology of the 1979 Iranian Revolution – the emphasis on nationalization of industry, "self-sufficiency" in economics, independence in all areas of life from both the Western (and Soviet) world.

Al-e-Ahmad "was the only contemporary writer ever to obtain favorable comments from Khomeini", who wrote in a 1971 message to Iranian pilgrims on going on Hajj,"The poisonous culture of imperialism [is] penetrating to the depths of towns and villages throughout the Muslim world, displacing the culture of the Qur'an, recruiting our youth en masse to the service of foreigners and imperialists..."[244]Like Al-e-Ahmad, Ali Shariati (1933–1977) was a late twentieth century Iranian figure from a strongly religious family, given a modern education, exposed to Marxist thought, and who reinvented Shia religiosity for those with secular education.

Khomeini was able to win over Shariati's followers with his forthright denunciation of the monarchy; his refusal to join fellow theologians in criticizing the Hosseiniyeh Ershad (a non-traditionalist venue where Shariati often spoke); "by openly attacking the apolitical and the pro-regime 'ulama; by stressing such themes as revolution, anti-imperialism, and the radical message of Muharram; and by incorporating into his public declarations such `Fanonist` terms as the `mostazafin will inherit the earth`, `the country needs a cultural revolution,` and the `people will dump the exploiters onto the garbage heap of history.`"[247][note 6] Socialist Shia believed Imam Hussein was not just a holy figure but the original oppressed one (muzloun), and his killer, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate, the "analog" of the modern Iranian people's "oppression by the shah".