Kibbutz communal child rearing and collective education

Communal child rearing was the method of education that prevailed in the collective communities in Israel (kibbutz; plural: kibbutzim), until about the end of the 1980s.

Non-selectivity was a fundamental principle of collective education; every child got 12 years of study, they took no tests whatsoever, and no grades were recorded.

[3] Fathers were supposed to bond with their children through quality time much more so than in a non-kibbutz environment, where they may be required to spend long hours at work.

Kibbutz people believed that as the necessary demands and requirements that are an essential part of every education process were eliminated from family life, the relationships between parents and their children got a chance to become much more moderate and harmonious.

In the early years of the kibbutz, parents were not allowed to enter the babies' house freely, as it was considered best to keep the place clean and orderly and let the nanny do her work.

As years went by, the attitude became more relaxed in this matter and parents were allowed to visit their offspring during the day, in order to spend time together and establish emotional bonding.

The arrangement of the newborns' house, its equipment and playground, and the correct way of offering toys in the right stage, were all believed to create the proper stimuli and the environment that might best fit babies, in order to avert boredom and satisfy the toddlers' emotional needs.

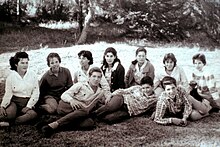

[7] The founding fathers of the collective education strongly believed that by this age the group held a major significance for its members.

This was the place for them to clarify their personal and social concerns, and this way the group was believed to function as the best setting to educate the youngsters and mold their characters.

Although all children of the collective education had similar life conditions and even though public opinion was highly considered, educators were proud to stress the fact that individuality remained crystal clear; they were very much willing to support artistic creativity (writing, drawing, and music), journal writing, and reading of books.

Putting forth an effort, moral behavior, and social involvement were seen as equivalent to academic achievements, and so was youth movement leadership.

Children- and youth-societies were considered "living organisms made up of dissimilar persons, each needing its individual attention".

[9] In order to stay true to life as they understood it, the kibbutz education adopted an inter-disciplinary method of learning.

The high school curriculum was divided in two: Humanistic (literature, geography, society, and economics) and realistic (physics, chemistry, and biology).

In addition, the curriculum included languages: Hebrew, English, and Arabic, mathematics, gymnastics, painting, music.

Everybody at school, including students and the education team, would read a book and then debate the dilemma it brought up, such as a controversial character.

The school would create a court which had members from all the youth society groups: a defendant, judges, prosecutor, a defense, and witnesses.

Skills such as weaving, sewing, knitting, metalwork, and carpentry were taught as an intermediary between work and study as a part of the curriculum, so it was possible for diligent students to become semi-professionals.

They supervised the activities at the schools, had teachers' guidance programs, provided consultation to families of children with specific needs, published, set budgets, and determined the standards.